The Presidents of the Society of Bowdoin Women are all listed on the back of the 1968 pamphlet. Each one of them, save the very first President, is identified by her husband’s given name and surname: Mrs. George W. Burpee, Mrs. Chester B. Abbott and so on. Even the first—whose very name the pamphlet memorialized—included the patrilineal married name as a parenthetical (Mrs George Riggs).

It was a long time ago, but the summer of love was just a year away, the term bra-burning would enter standard usage after the 1968 Miss America Pageant, and in three short years the college would admit women giving a whole new meaning to the Society of Bowdoin Women. A decade later to the applause of local teenagers, a woman would appear bare chested in her senior photo in the college yearbook.

So who was Mrs. George Riggs and why did she warrant her own name at the top of the list while all the other presidents were named as derivatives of their husbands?

She was Kate Douglas Wiggin, a celebrated author of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century whose many books include Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. A Mainer, of sorts, she was the first president of the Bowdoin Society of Women.

“The choice was a happy one. Mrs. Wiggin shared with her friend and fellow Maine author, Sarah Orne Jewett, the distinction of being the first women to have received the Bowdoin degree of Doctor of Literature. President William DeWitt Hyde described them in 1904 as ‘The only daughters of Bowdoin.’ ”

So by virtue of her honorary degree from Bowdoin, and the imposing figure she casts in the photo that memorialized the event, Kate Douglas Wiggin qualifies for Faces of Brunswick, Maine.

Wiggin was not born in Maine, but moved here as a young person after the death of her father, and lived in Portland for a spell. The family relocated to Hollis and a boarding house after Wiggin’s mother remarried. For a time she attended the Gorham Female Seminary, a predecessor to the Gorham Normal School and what is now known as the University of Southern Maine,

A family illness triggered a move to California and led eventually to teaching positions and a position training teachers for kindergartens. Wiggin was not her birth name but the surname of her first husband, a San Francisco lawyer she married in 1881. But Wiggin was her name during the beginning of her literary career in the 1880s. She relocated to New York during the end of the decade and back to Maine after Mr. Wiggin’s 1889 death.

From this time forward she spent substantial time in Hollis. Some of her earlier works which had been self-published had been reissued in 1889 by Houghton Mifflin. Timothy’s Quest, published in 1890 confirmed her literary career and the remainder of her life was devoted to writing and travel to support a schedule of lectures and readings. On one of these trips abroad she met and married George C. Riggs, of New York. On-line sources suggest Mr. Riggs was an advocate for Wiggin’s literary career and that her out-put increased during their marriage. To be sure her most famous work, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm was published during this period in 1903.

In 1905 she purchased a home in Hollis and renamed it Quillcote, or House of the Pen. Some sources suggest it was a farm she had admired as a child in the area, others suggest it was the very boarding house she had occupied as a child upon her move from Portland.

Where did these books come from?

The Rabbit Hole has many chambers.

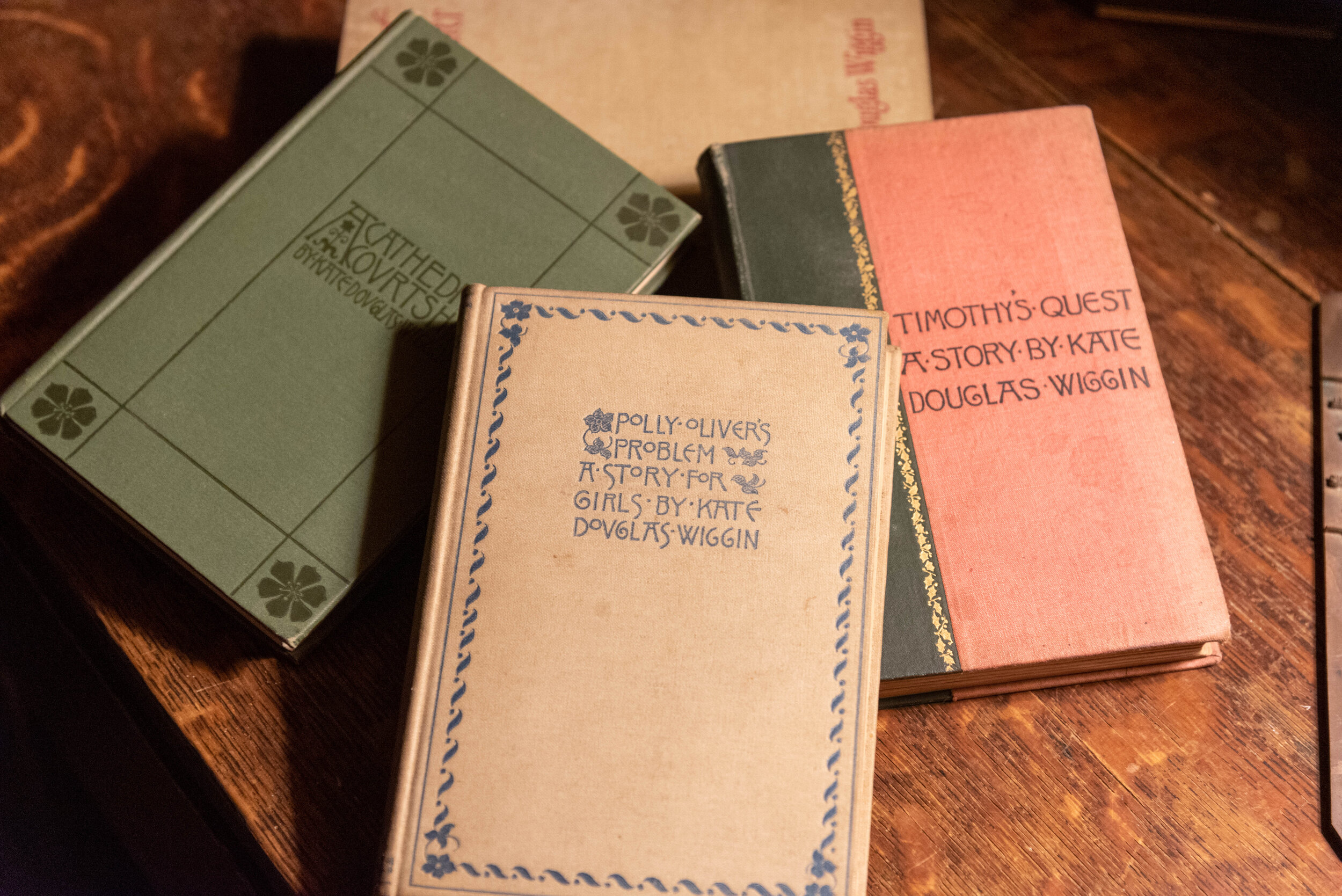

These books come from the collection of Bessie Singer, herself a graduate of the Gorham Normal School and my wife’s grandmother. She and her husband were avid book-collectors. Their home in Bath, when acquired by us, was lined with built-in bookshelves on a common wall in the living room adjoining the neighboring property. In addition rough-hewn make-shift shelves lined the hallways, spare rooms, and many of the interior walls of the house. Regrettably many of these books were damaged beyond preservation or use as the result of a plumbing failure before we acquired the house. Only those books on the built-in shelves against the common wall were salvageable. Dominating this collection was a substantial store of local interest, often by Maine authors, or about Maine, together with a collection of various American works from the nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth.

Distractions in Inventory Control: What was Polly Oliver’s Problem?

After posting some of these photos on Instagram I got an inquiry, what was Polly Oliver’s Problem?

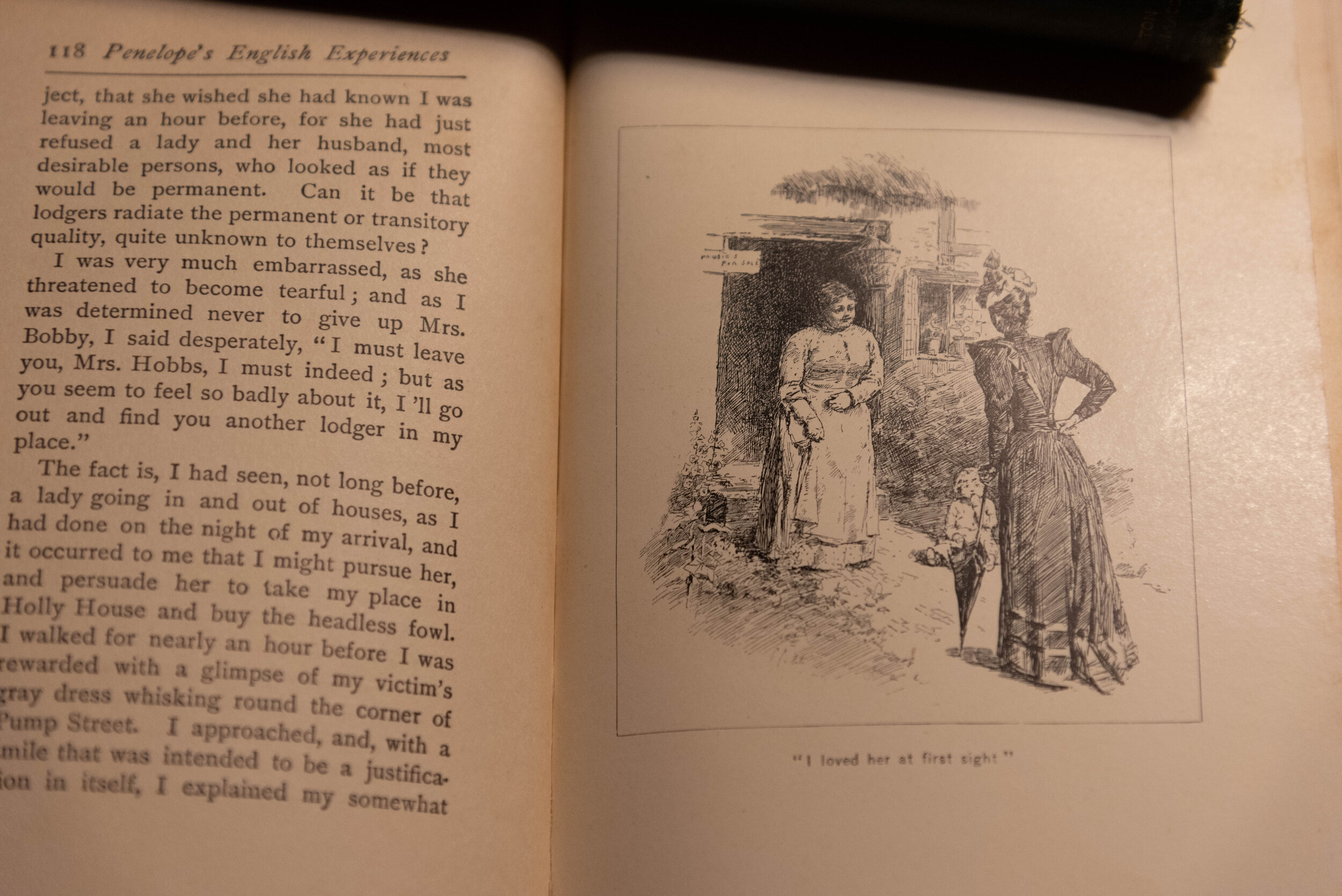

I wondered if it might be of the medical variety based on the title of chapter 3: “The Doctor Gives Polly A Prescription.” But exploring the first few pages a little more carefully it seems apparent that her problem was either “the boarders,” or the “Chinese.” As she plots to rid her house of boarders, Polly contemplates a banner, “‘The Boarders Must Go!’ to hasten their departure and then considers “To a California girl it is every bit as inspiring as ‘The Chinese Must Go!’” This slogan was common in cartooning and anti-chinese propaganda of Wiggin’s nineteenth century west coast experience. Wiggin makes a play on it as she remonstrates with her mother about the burden of keeping a boarding house.

“The Chinese never did go,” her mother informs her.

“Oh, that’s a trifle; they had a treaty or something, and besides, there are so many of them, and they have such an object in staying.”

Well. Whatever Polly’s problem was it certainly was not political correctness. I have yet to fully explore her problem. In any event, I expect everything will turn out well enough.

As it happens I am deep in another nineteenth century work connected to Maine invited by its woodsy cover art, The Hermit, a 1903 work by Charles Clark Munn. Its binding is in fine shape and the pages of this Grosset and Dunlap edition flow just as smoothly as something printed in the last couple of years. I have little fear of diminishing its value as I read it.

The Yearbook.

Sometime in the fall or winter of 1979-80 I went to the Bowdoin admissions department for an interview. Admissions was then housed in the two story building across the plaza from Coles Tower, which was then known as “the senior center.” The decor was vaguely Danish modern and the low slung table in the waiting room held a collection of yearbooks and other college paraphernalia spanning the years. As a faculty brat I’d seen a lot of it before, we had a decent collection of yearbooks in the house by which we marked the passage of the years by my father’s progression from young turk to distinguished lion of faculty.

I knew which one I needed to see. 1979. I even knew about where in the book to find her. I didn’t have the page number memorized, but I knew she was toward the front of the seniors section in the upper left-hand corner of a page on the left.

She was gone. Scissored out. A perfect 4” by 6” gap where she belonged. I lifted my eyes and was met with the tight lipped smile of the admissions department secretary. Yes, she admitted. She had cut a photo out. “Not everybody needs to see everything.”

Was this some sort of test? Part of the admissions gambit, root the perverts out early? Or was it just to put the pressure on immediately to raise the anxiety level for the meeting with the admissions officer. Calm down. Not everyone coming through these doors knew what was on page 102 of the 1979 Bowdoin Bugle. In fact, maybe only I did.

How did this woman in the admissions department, unknown to me to that point, know I would look right there?

I sat there bereft and gradually grew indignant at this act of vandalism? What about the kid on the other side of the page? Not right. You’ve denied some student their chance at immortality here in the admissions department. What about that person, having their senior picture cut out because the secretary found the flip-side a little racy? The injustice. I was enraged on behalf of the missing student from the class of 1979.

I do not recall any of the other details of my interview, but I was admitted. I still have that 1979 yearbook. Intact. On the back side of page 102, at the top of page 101 is an uncaptioned candid of three girls laughing, standing by a car, its doors flung open, on the road side. It is terribly over-exposed; the detail in the girls’ faces is completely lost. Probably only they will even recognize themselves in the photo.

1979 Bowdoin Bugle, barely edited