A Tree.

A fixation for humankind since the beginning. It stands to reason. According to the story, the tree made its debut on the third day, three long days before man made his appearance. And trees are the most ecumenical of symbols; we have the Bodhi, Banyan, and scores of trees sacred to other beliefs.

A single tree always captures the human imagination. Consider this snippet from Edna St. Vincent Millay spotted recently in the Instagram feed of the Millaysociety:

Thus in the winter stands the lonely tree,

Not knows what birds have vanished one by one,

Yet knows its boughs more silent than before:

I cannot say what loves have come and gone,

I only know that summer sang in me

A little while, that in me sings no more.

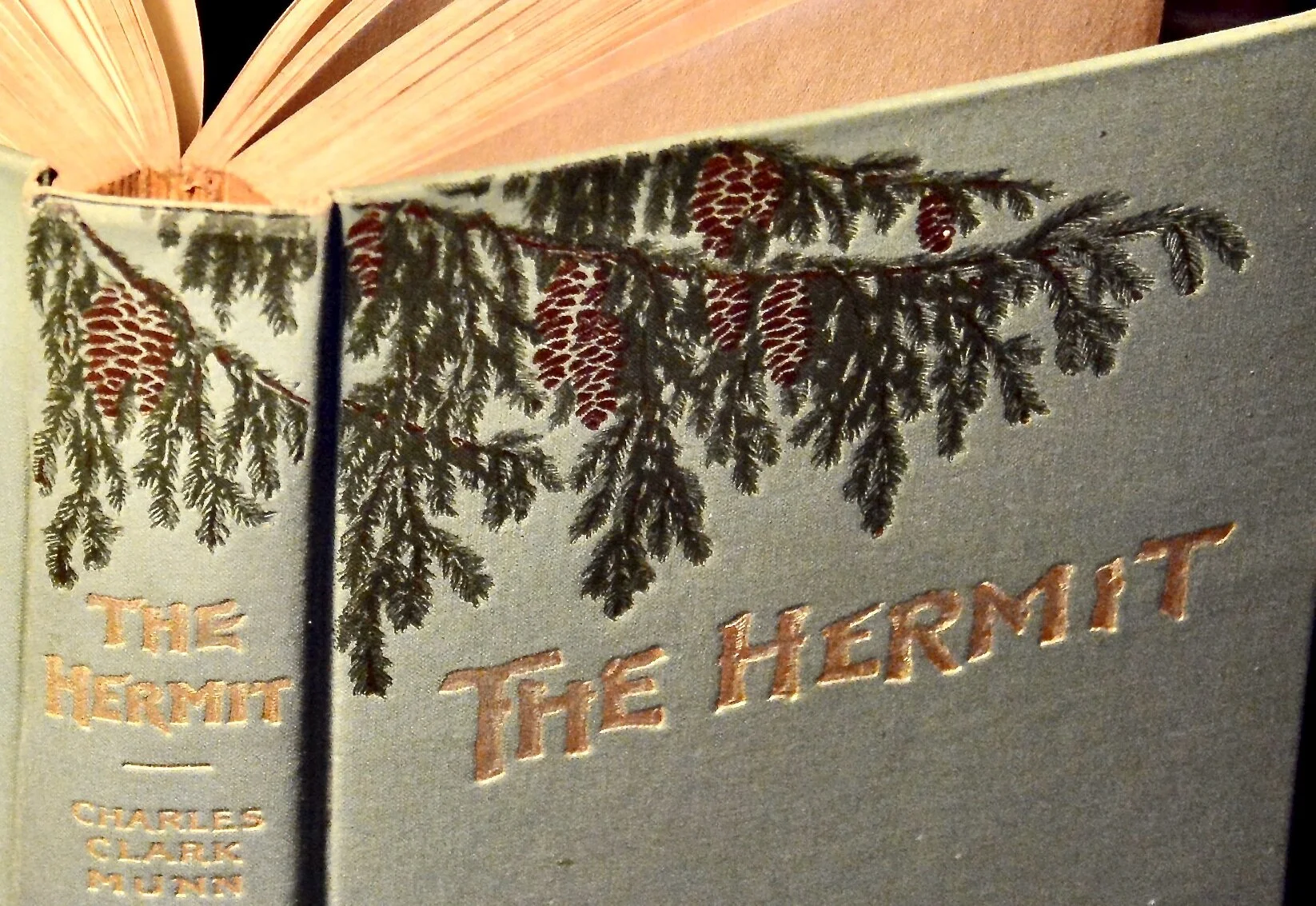

Against a backdrop that pre-exists humanity it is hard not to get drawn in by the cover of The Hermit, published in 1906 when dust jackets were still a relatively new phenomenon that had yet to suck all the decorative skill and craftsmanship off of the “boards” and onto the disposable and more fragile dust jacket.

The cover is both bold and simple. The title is well preserved bold gilt lettering in a woodsy font like hand-hewn lodge poles. The author’s name, also in gilt, is in type reminiscent of modern life in 1906. It could have appeared on the letterhead of the book’s protagonist, Martin, a man who had left small town North America to win fortune in the city in some vague but remunerative profession.

But the main decoration is a simple, detailed rendering of the bough of a tree, heavy with cones. It is dark, but rich, mainly green with some reddish brown peaking through on the cones. The blocking and embossing have texture and invite a touch. It very nearly smells of spruce.

But that is the best thing about the book

Munn’s descriptions of nature and topography are good, the relationships between the guides and the “sports” realistically, if awkwardly, describe the dymanic. And the relationships between men of equal status is plausible. Martin seems on a near par with Dr. Sol, his old school mate who remained in town, but a patronizing condescension pervades every other relationship. Editing and continuity are poor too. One thread that involved two lengthy trips into the woods, a gunfire riddled entanglement between a supposed murderer holed up in a booby-trapped cabin and two untrustworthy game wardens consumed a pair of chapters but ended abruptly with “it must be recorded that not until years later did Martin find out who really occupied this inhospitable cabin on the Moosehorn, or what the ultimate fate of McGuire was.” The bigger mystery is why it tied up fifty pages of text without having the slightest relationship to the remainder of the plot.

I read this book, cover to cover, because the cover art lured me in and because the book itself was in really good condition given its 114 years on shelves. It could be read without diminishing its market price (maybe ten dollars).

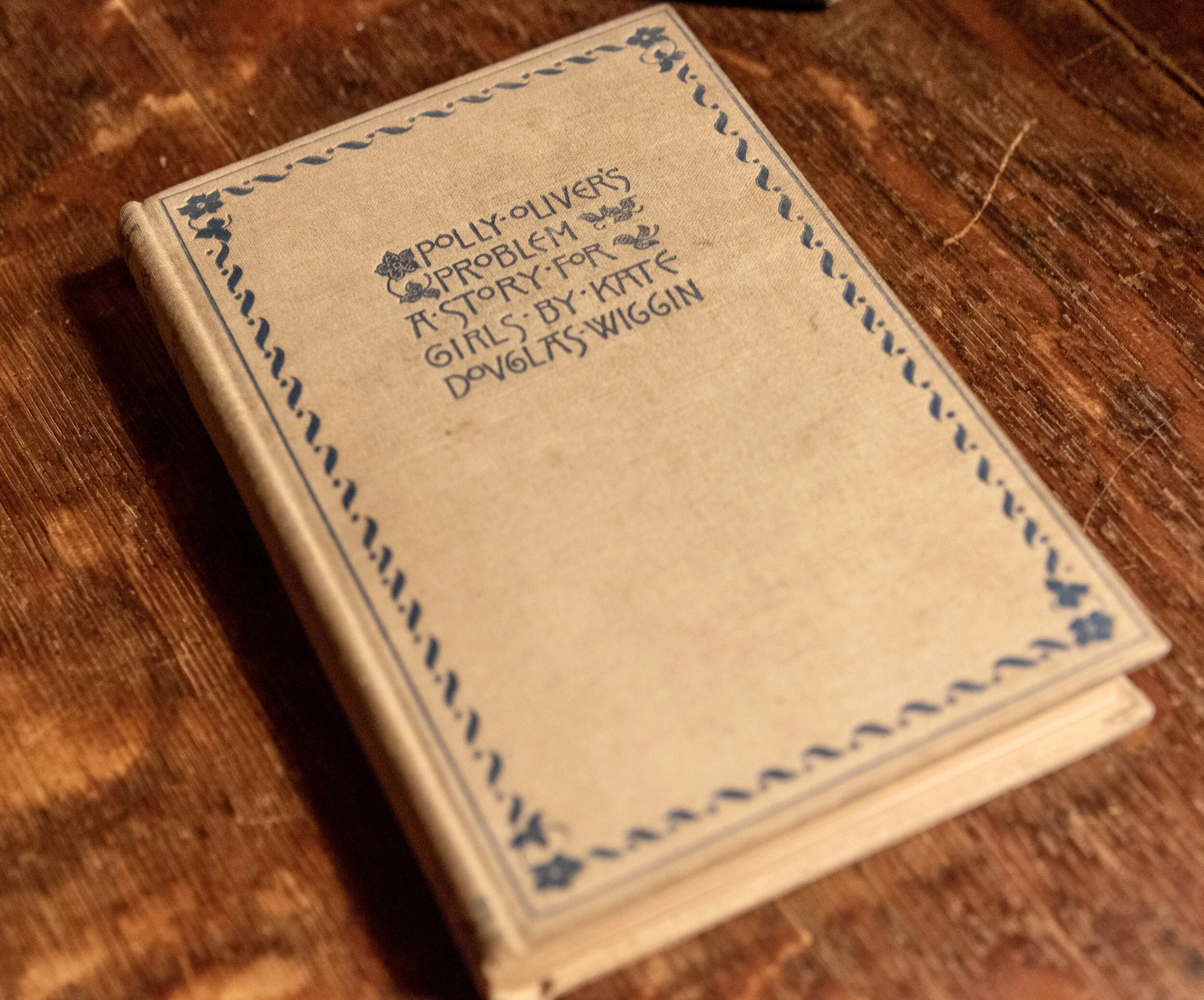

And that, according to rarebookschool.org, is the point: “Dust jackets were introduced near the end of the nineteenth century, and by the 1920s the jackets were decorated far more heavily than boards. But between 1830 and 1910, cloth covers were the first thing a customer saw, and bookbinders worked to make the covers attractive. The nineteenth century saw a wide range of decorative designs, fueled by the evolution of technology and taste. Each decade developed a recognizable style, which means that the date and often the intended use of a nineteenth century cloth-bound book can easily be judged by its cover.”

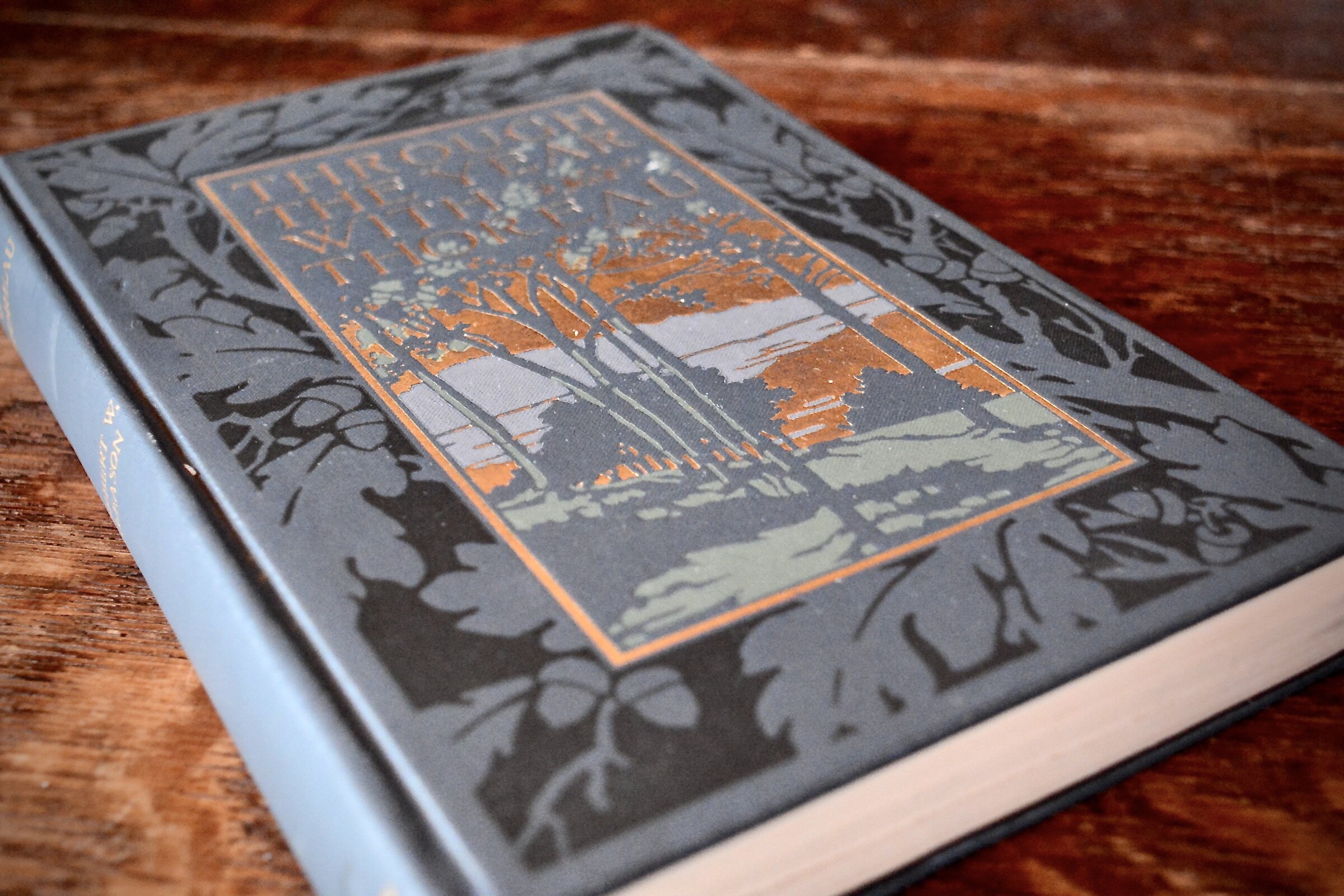

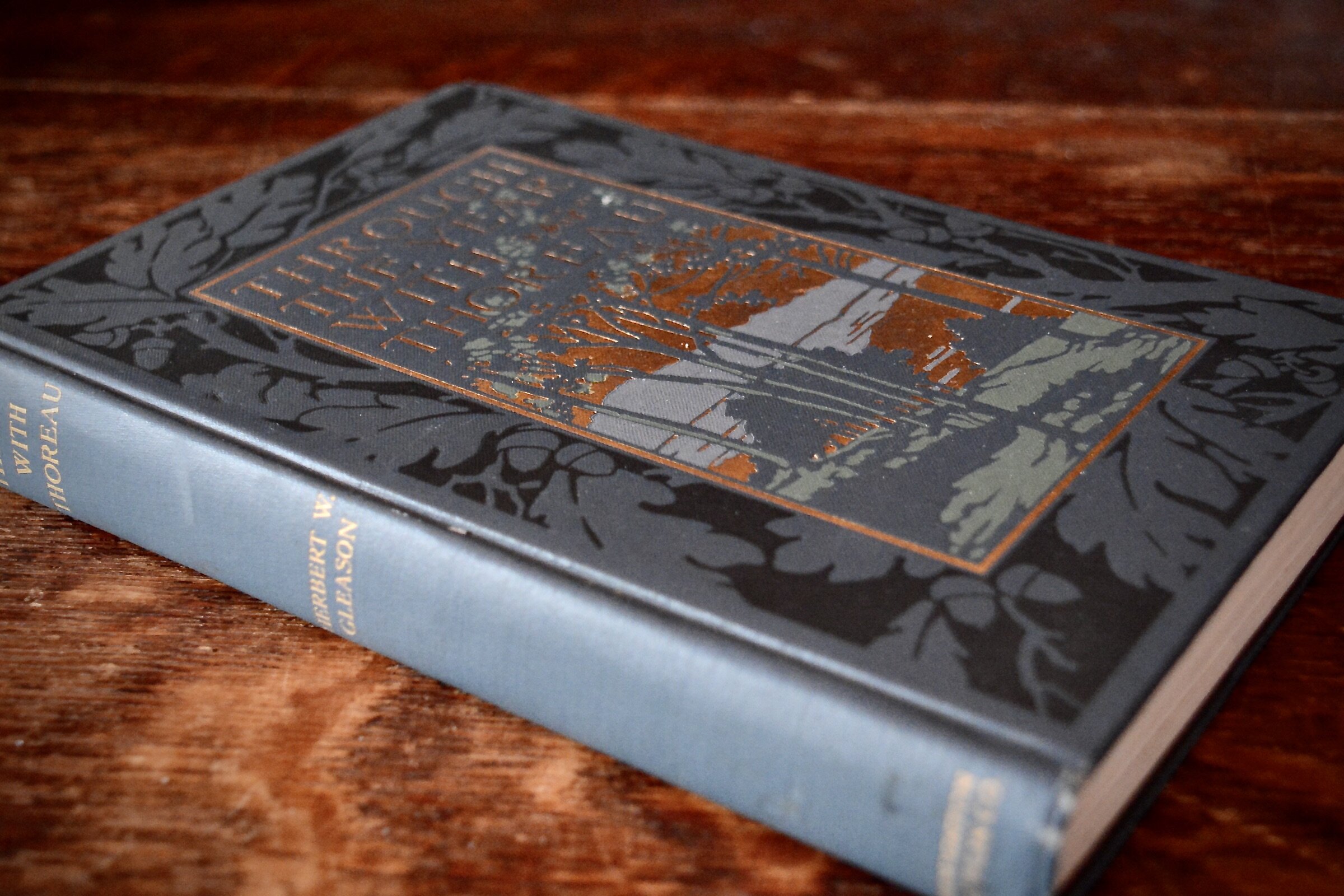

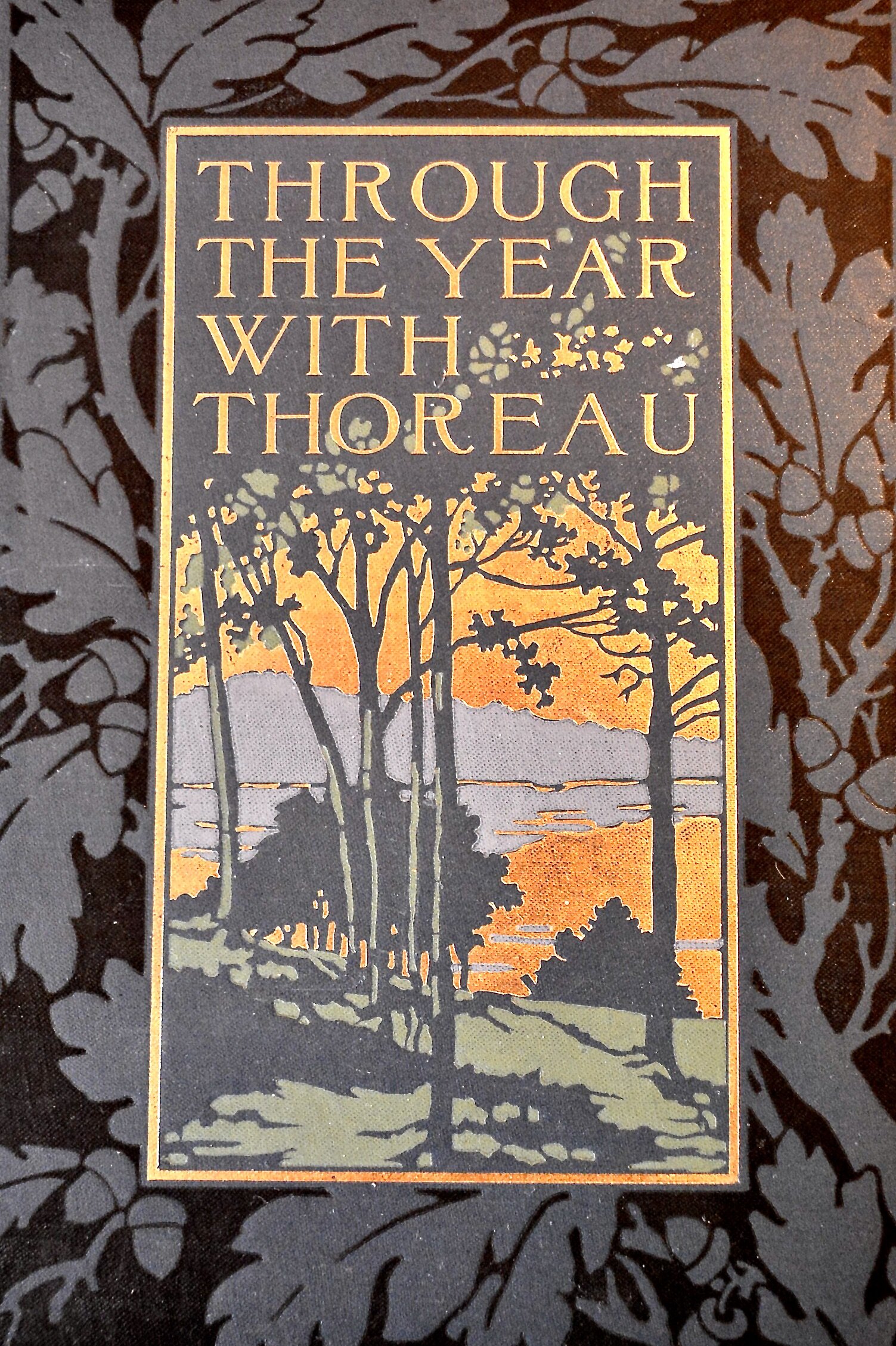

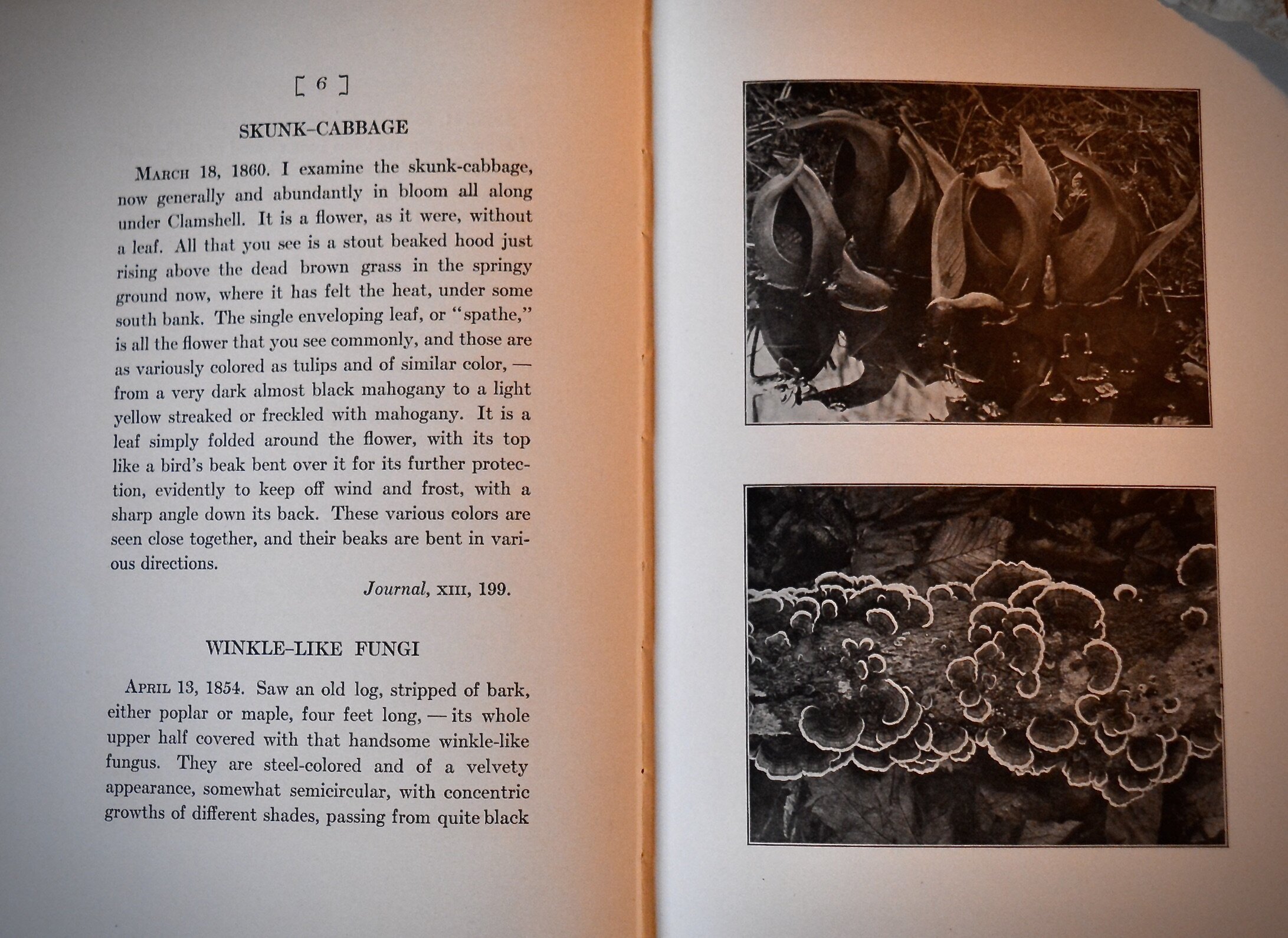

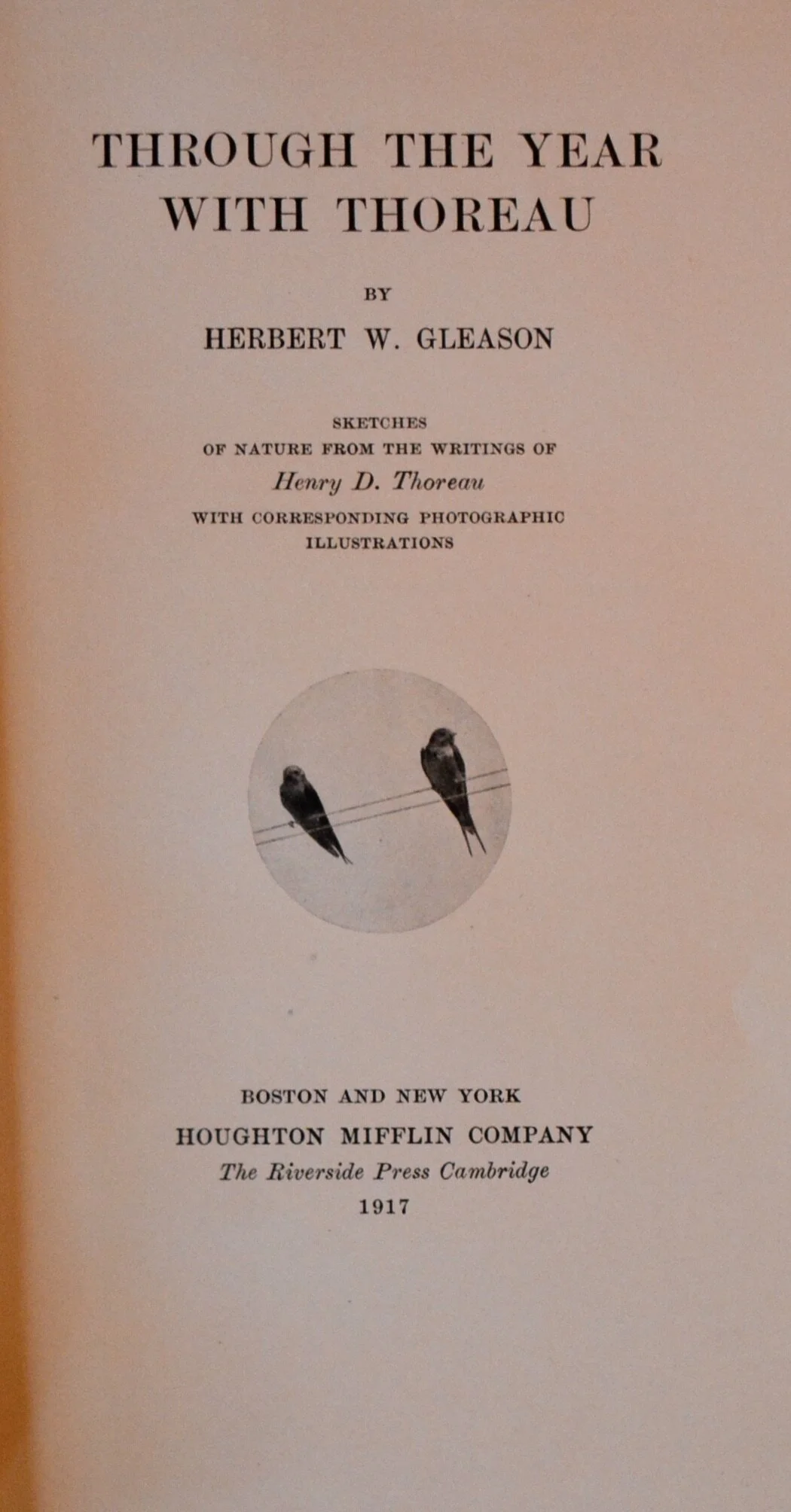

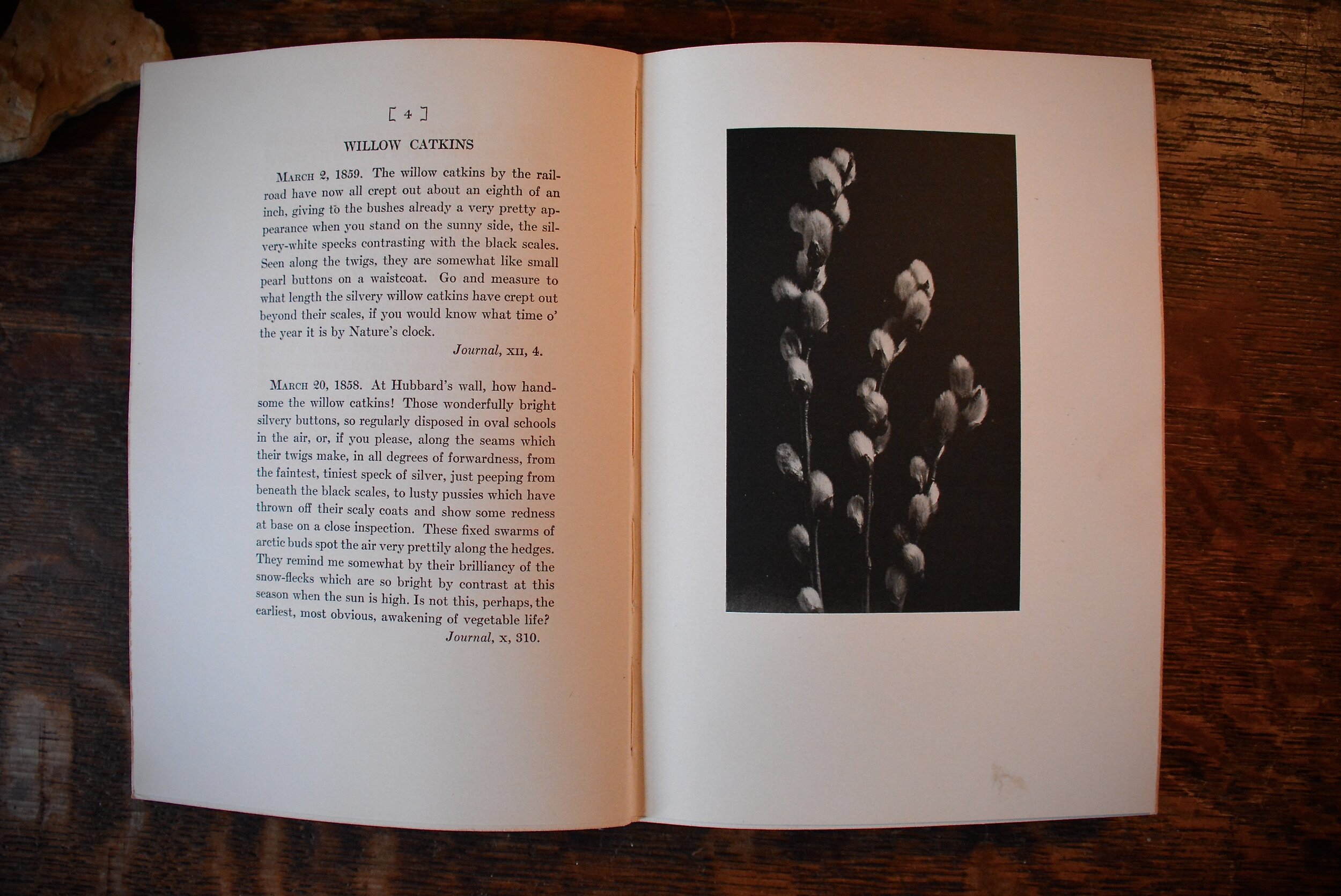

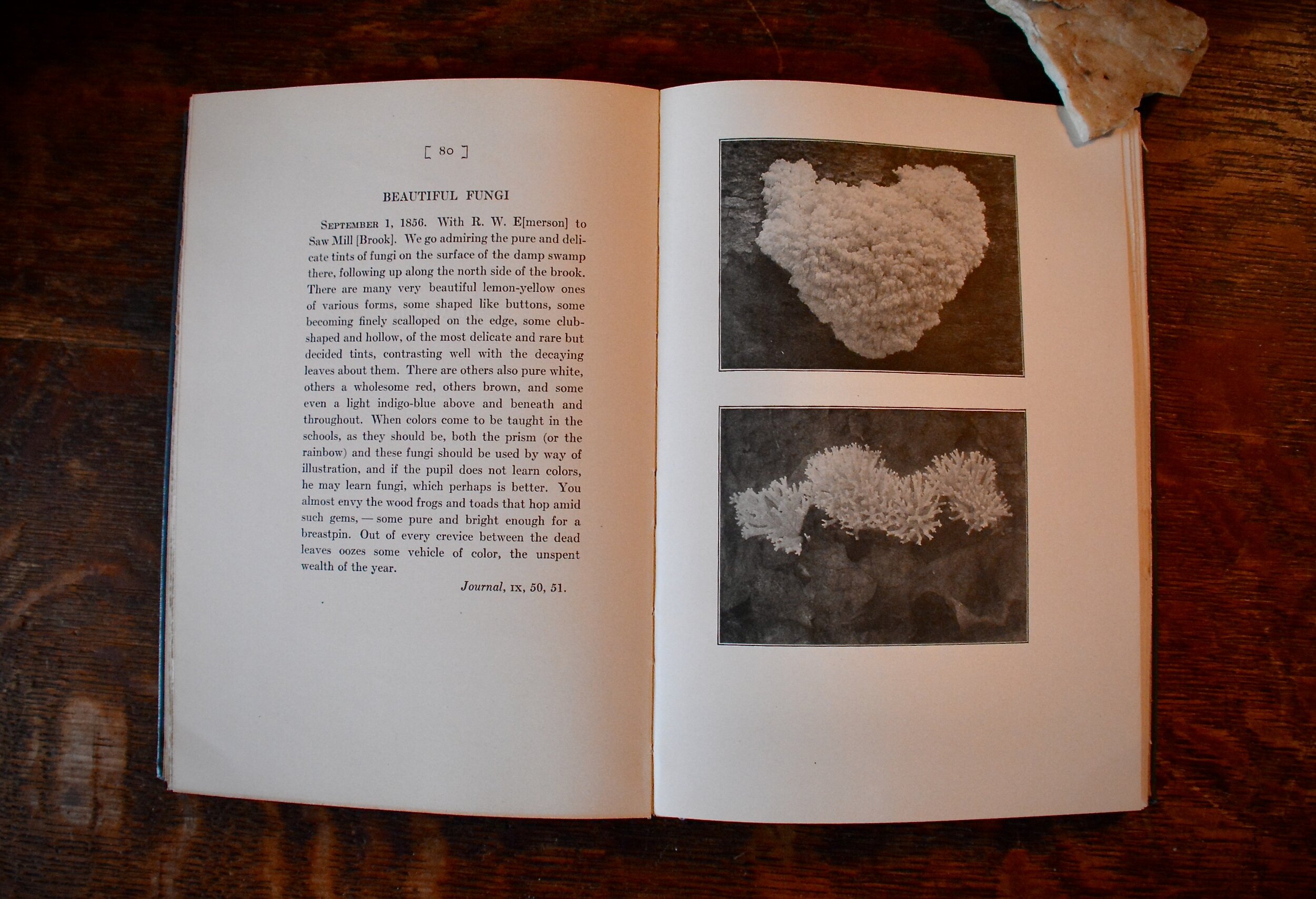

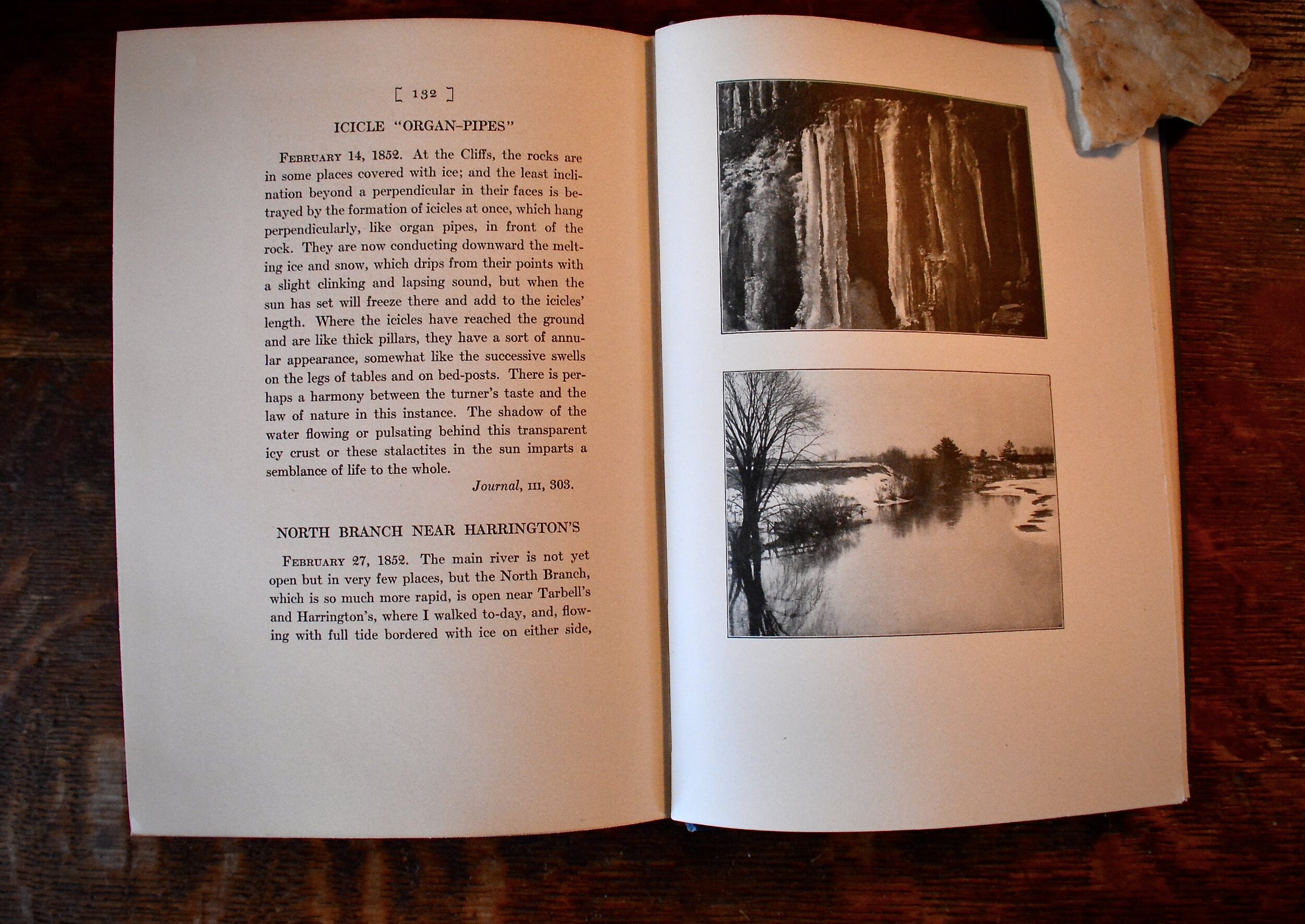

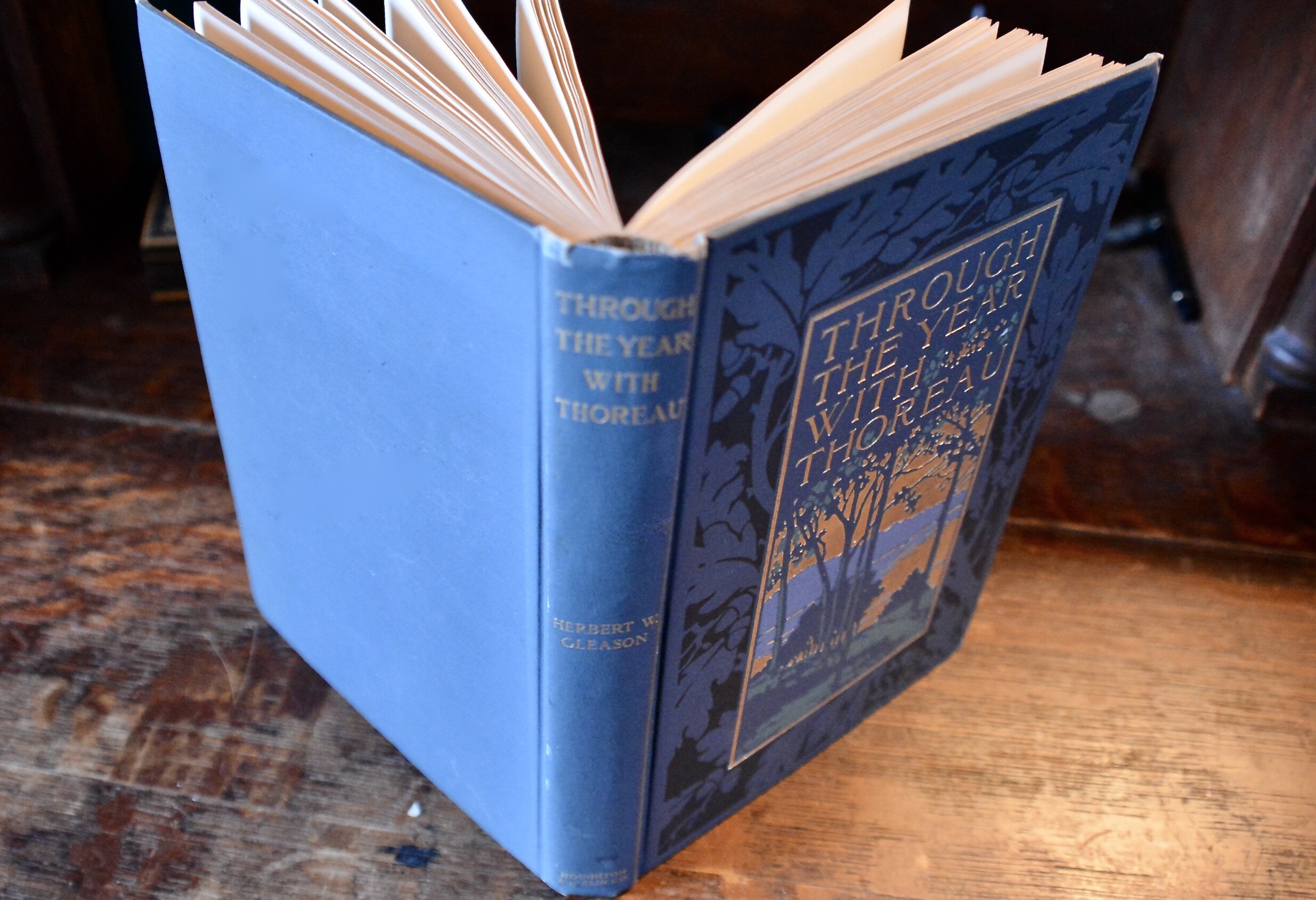

Another excellent example is photographer Herbert Gleason’s early twentieth century homage to Thoreau. Gleason followed several of Thoreaus perambulations and produced what we now call coffee table books. They tip the cap to literature and to Thoreau while providing a vehicle to showcase Gleason’s own photographic career. Through the Year With Thoreau is a loose month by month collection of Thoreau’s observations, coupled in each case with a matching photograph. For instance in early.April, Gleason matches Thoreaus paean to the skunk cabbage with some nice photos of—skunk cabbage.

(Gallery, nine images, click through)

A current online seller of the 1917 Houghton Mifflin edition focuses on the cover art. “Lovely pictorial decorated binding. Center of the front cover shows a woodland scene with lake with the title gold-stamped. This central tableau is surrounded by pine leaves and acorns in silhouette.”

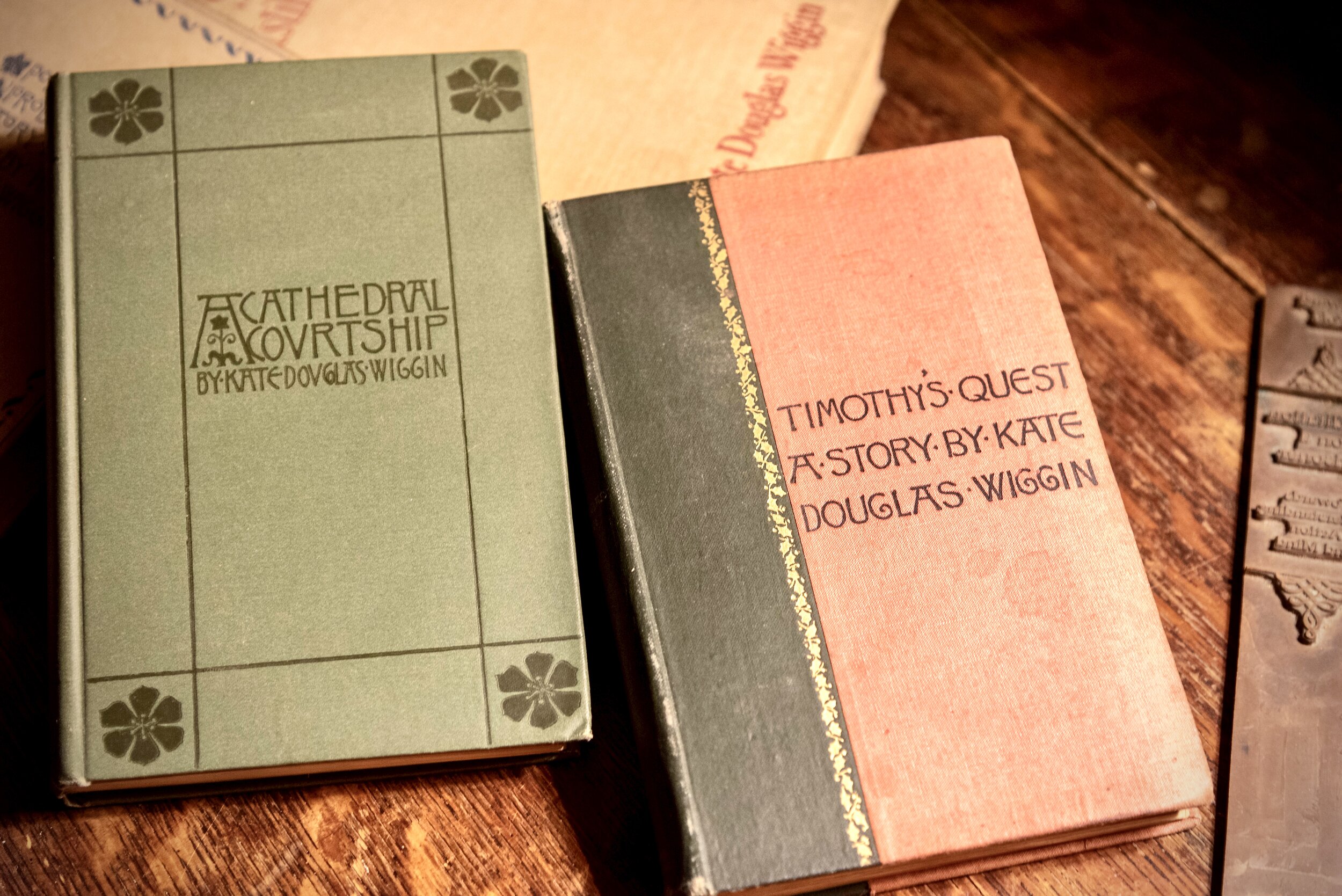

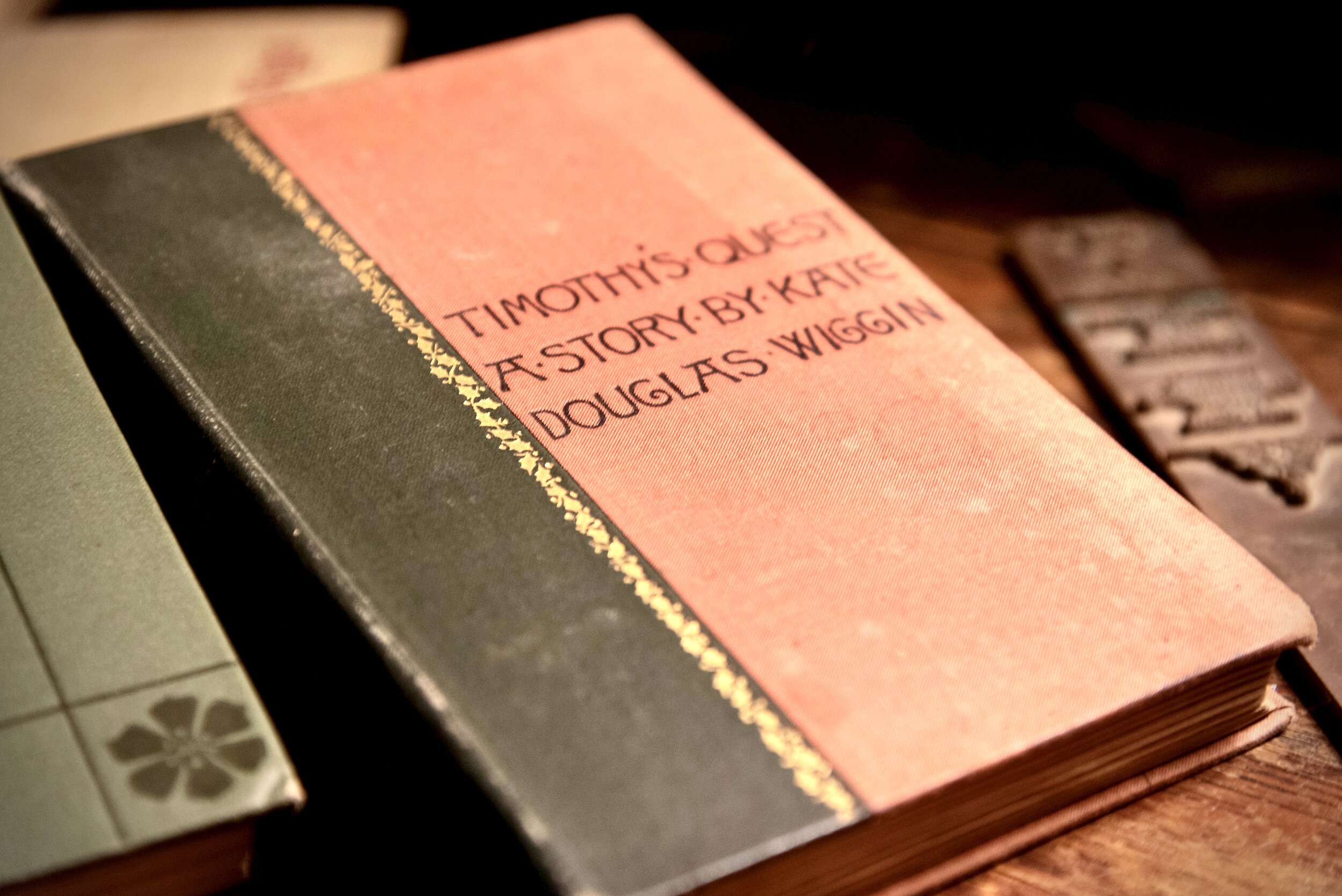

Another seller notes its copy has the rare dust jacket illustrated with the same illustration as is shown on the boards. Given the print date of 1917 it appears that cover illustration had reached its peak and was near its replacement by dust jackets alone. Every square inch of the front board on Through the Year With Thoreau is used. This contrasts with the relative spareness of the design on The Hermit and with much of some best known work of the previous two decades.

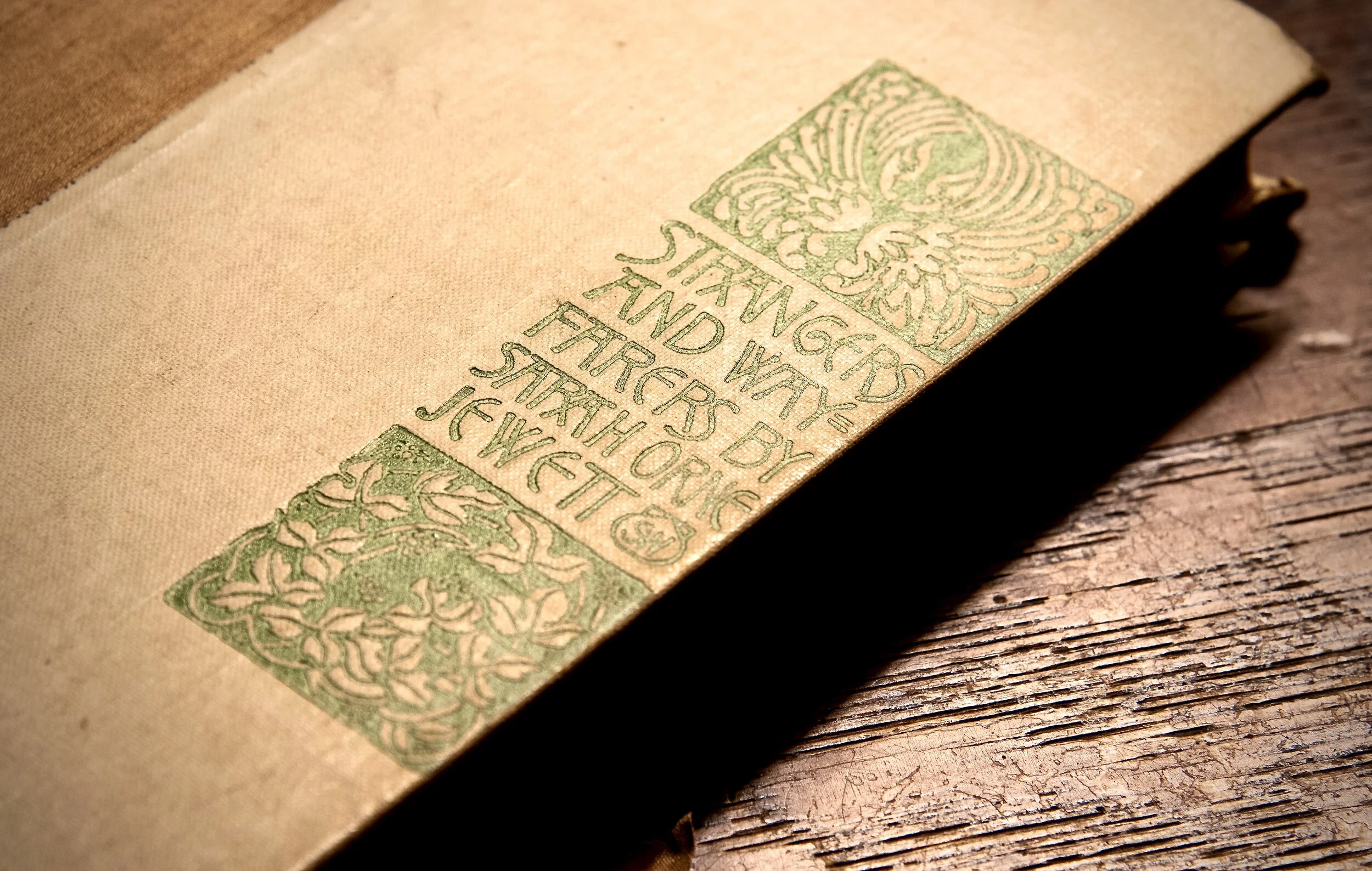

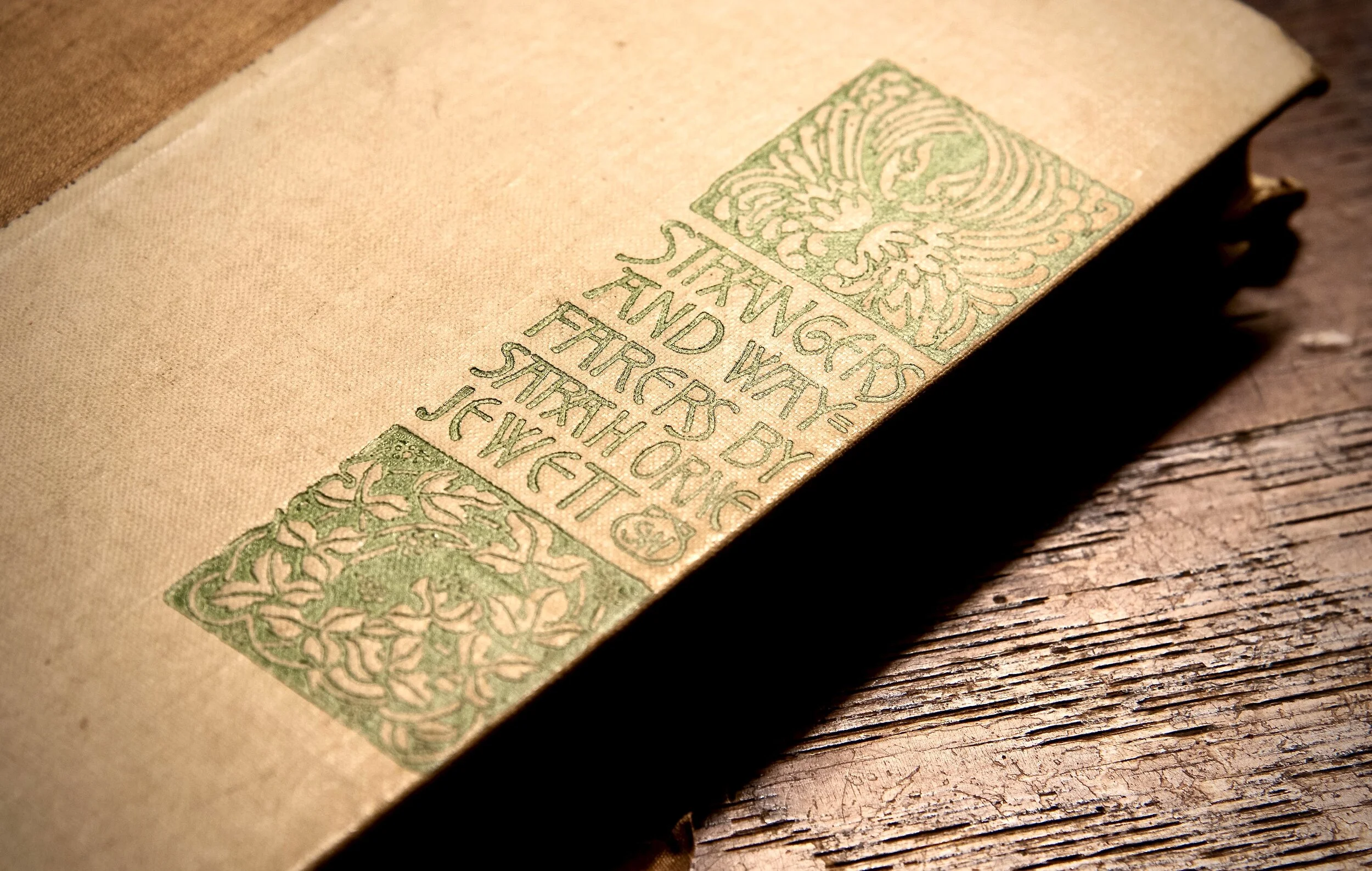

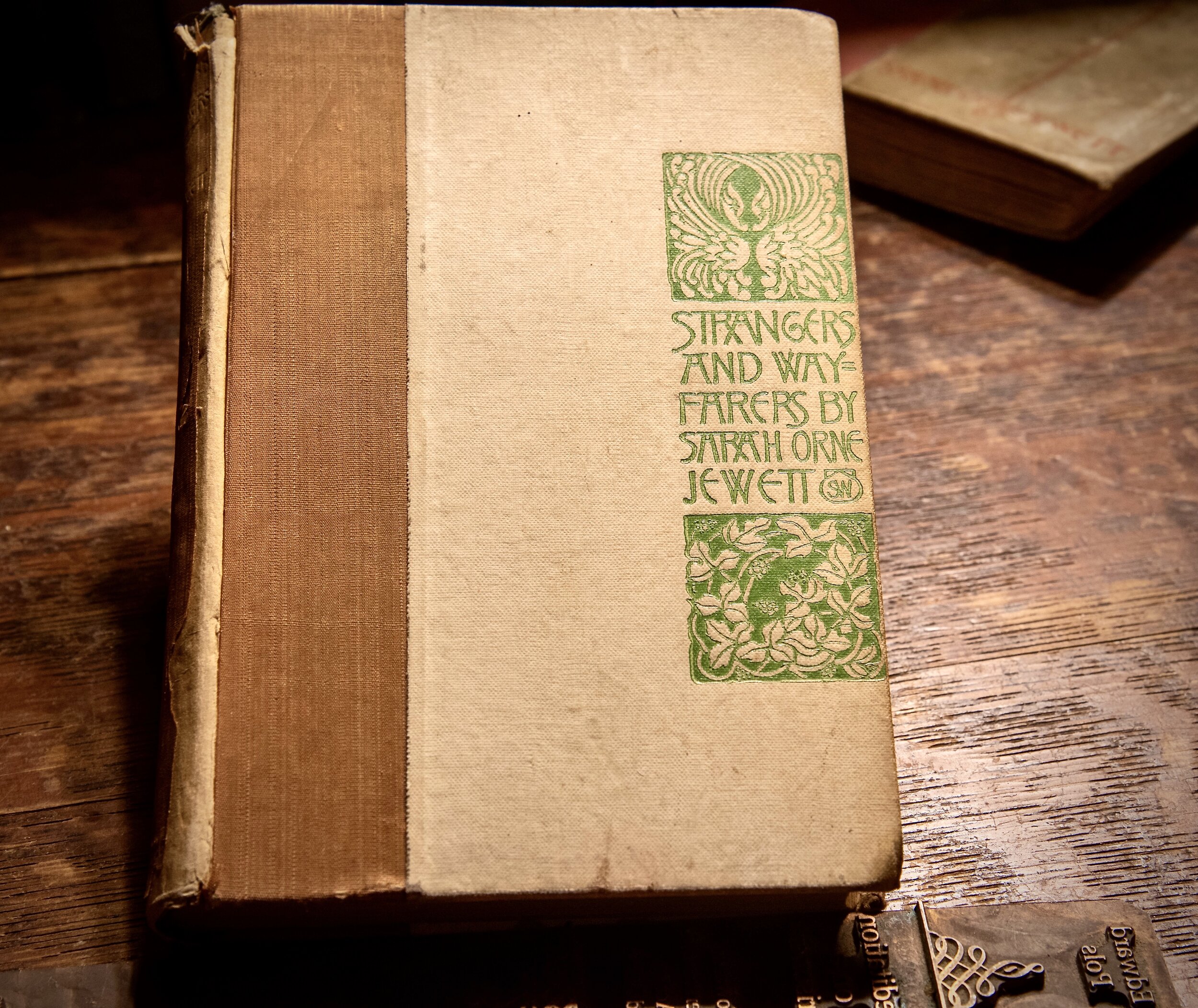

Sparseness, or subtlety, characterized the work of Sarah Wyman Whitman, a prolific cover designer bridging the nineteenth and early twentieth. Trees, or more generally, vegetation feature prominently in her work and she appears to have been among the first to be credited for her work, working the subtle monograph “SW” into her design. Whitman also received credit directly from one of the authors with whom she frequently collaborated, Sarah Orne Jewett. ‘In fact, Jewett, who only dedicated ten of her twenty books to her colleagues and friends, took great pleasure in inscribing her collection Strangers and Wayfarers to, “S.W: Painter of New England Men and Women/ New England Fields and Shores.”’ (see Publishers’s Online Covers linked below). By contrast in The Hermit and Gleason’s Thoreau tribute, as in most other illustrated books of the time, the illustrator is credited but the cover designer is anonymous.

Sarah Whitman’s “SW” can be seen in a circle just to the right of the author, Sarah Orne Jewett’s, name on the cover.

Whitman’s work is so central to the books she designed that the covers, in some cases, may be more important than the contents or authorship of the books themselves. A near complete collection of Whitman’s covers are in the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collection & Archives at Bowdoin College. Its collection of 328 covers is said to contain about 85% of Whitman’s complete works.

Completing this collection would make a compelling argument that—in some cases at least—a book should be judged by its cover.

—Benet Pols

(Gallery slideshow, click through)

Sources and other additional information:

Publishers’ Bindings Online details the collaboration between Sarah Whitman and Sarah Orne Jewett

The rarebookschool.org on judging 19th century book covers

Bowdoin notes its acquisition of a collection of Sarah Whitman’s covers

Nicole Morris details the realationship between Whitman’s book cover art and her stain glass work at the Worcester Central Congregational Church

A link to the Boston Public Library’s Flickr gallery of its Whitman covers.