1812. A War.

For an American anyway, I may know a lot about the War of 1812. As a Mainer, I have seen the masts of Old Ironsides, the USS Constitution, flickering in my periphery between the trusses of the Mystic River Bridge and the rooftops of Charlestown while headed to Boston. There she sits, everything there is to know about the War of 1812. I may even have visited her as a child on a school trip. After some thought, I can also tell you James Madison was president during this war; this, I know, because his wife Dolley, of snack cake fame, is reported to have rescued a painting of George Washington from the White House before the British arrived to burn it.

I do remain a little unclear on how the United States ended up “winning” a war in which the opposing side first managed to invade the capital, drive out the President, and burn down his house. It may have been connected to the fact that the British were also busy fighting the French and Napoleon in a separate war back on their side of the ocean. That’s a war I know less about.

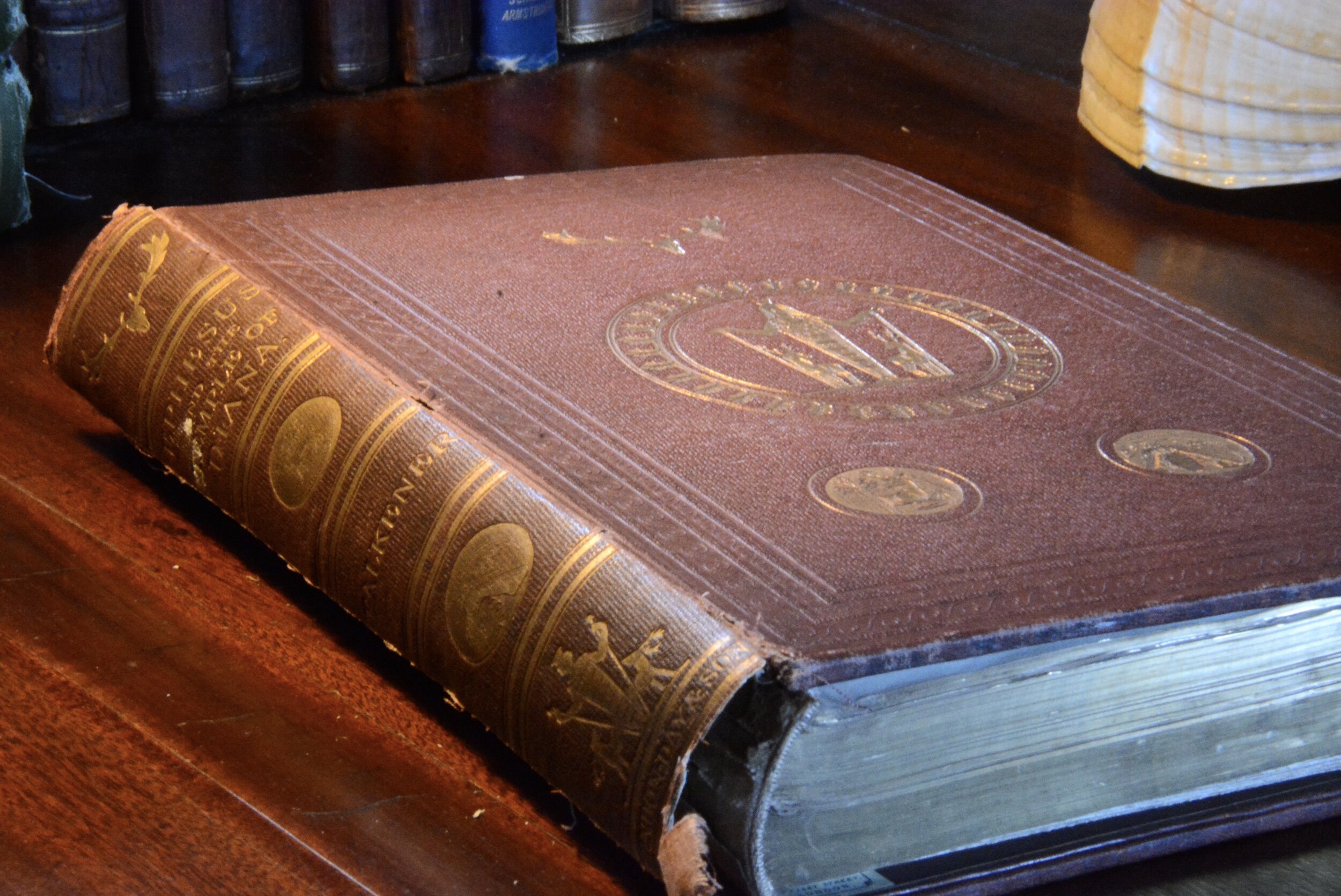

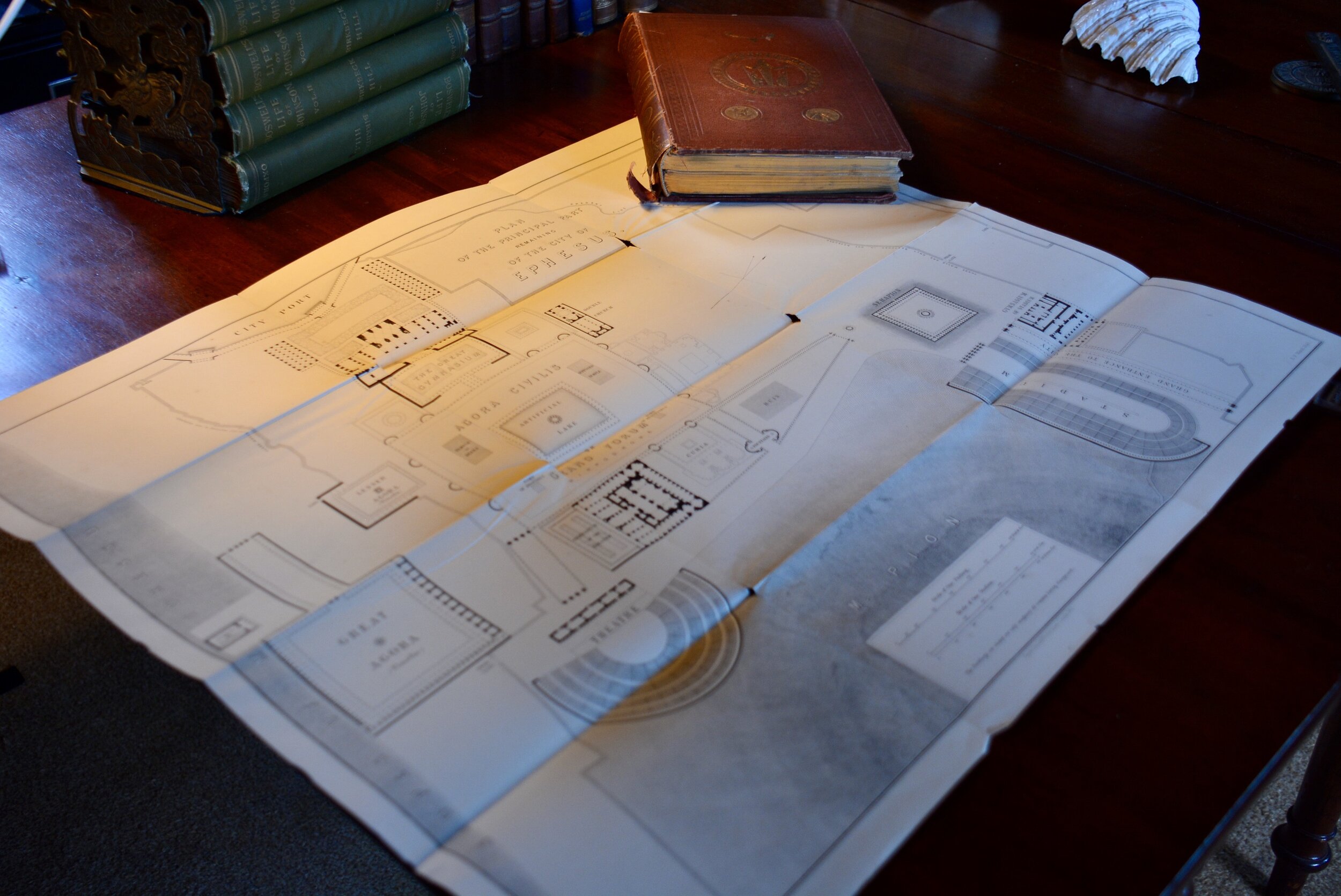

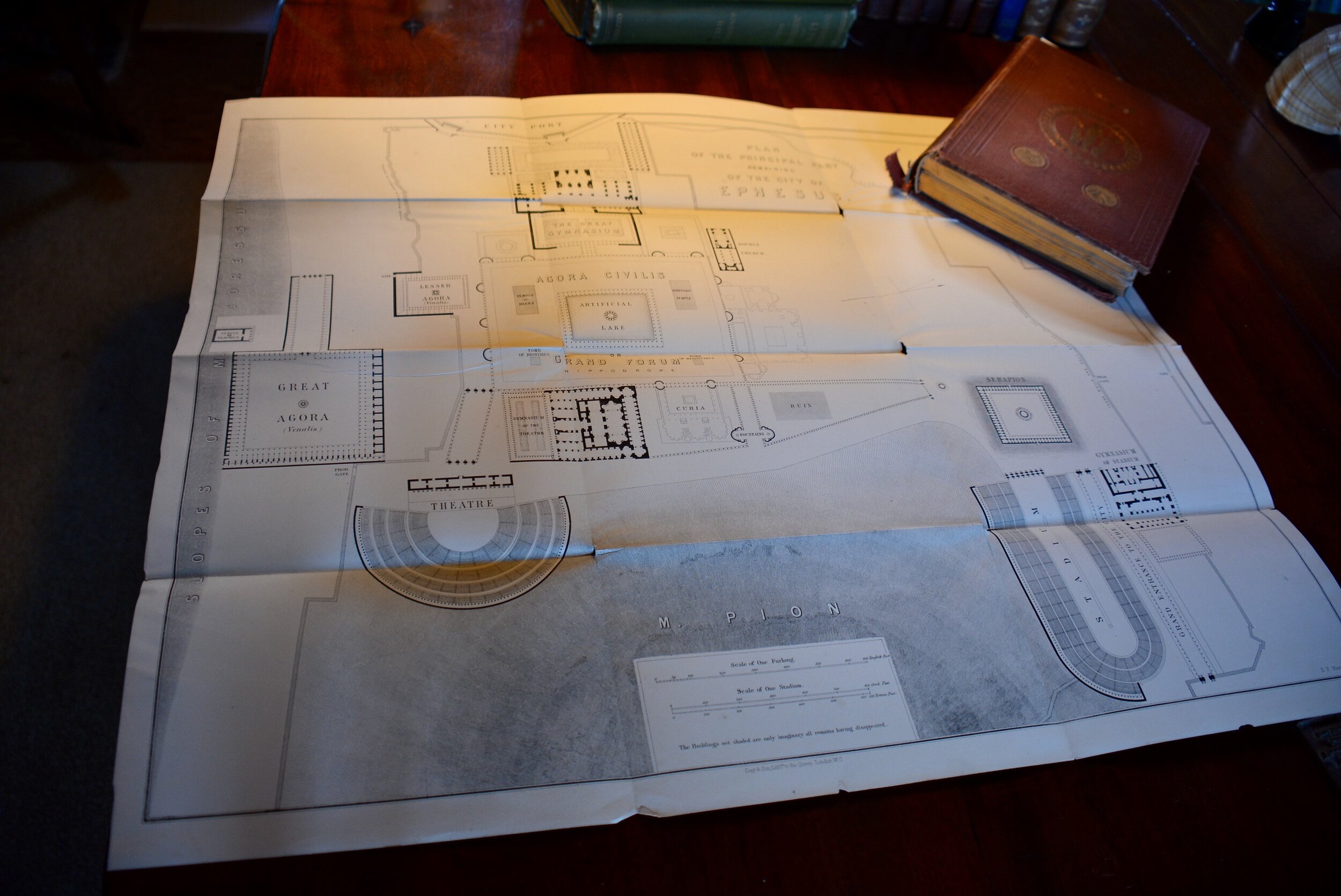

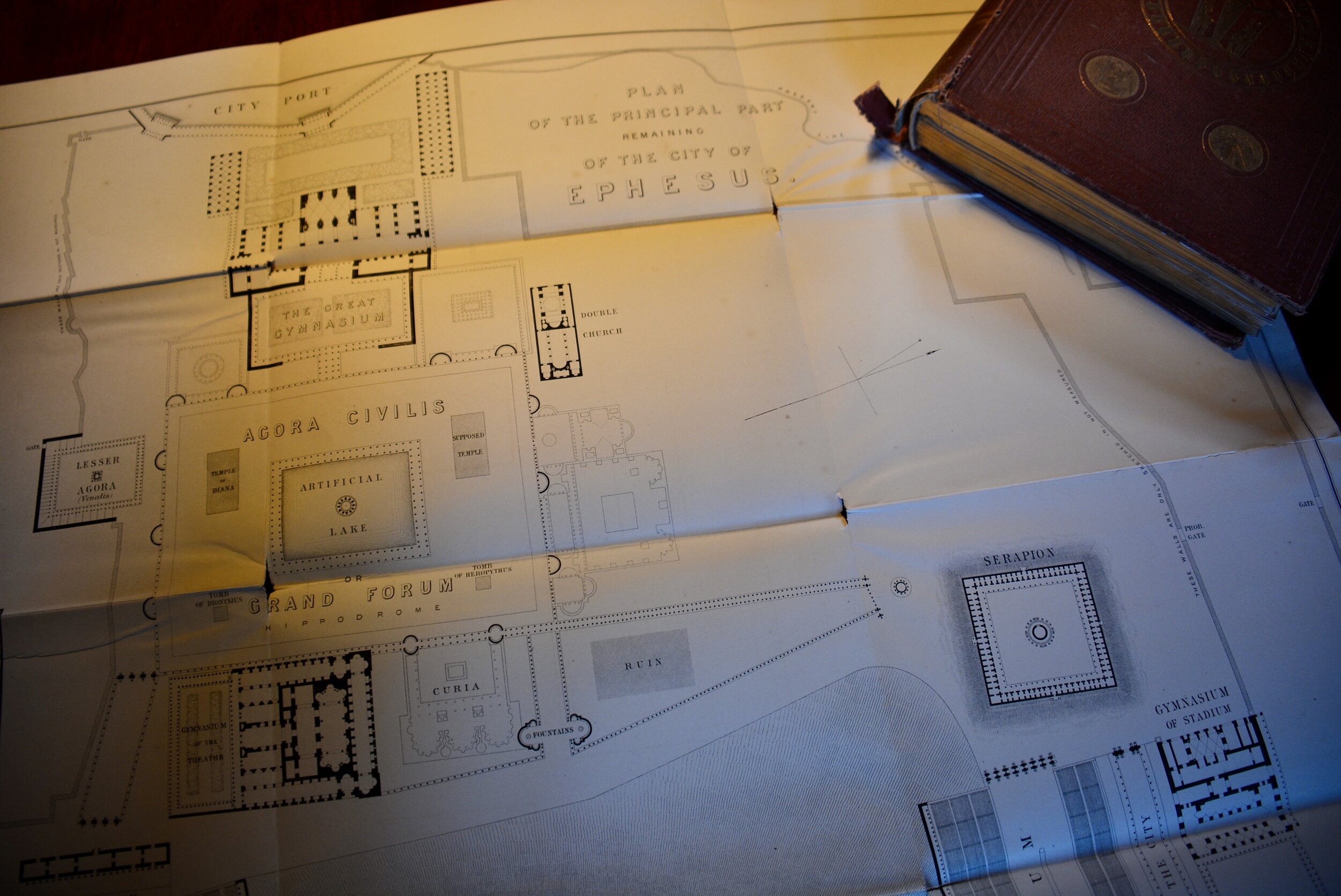

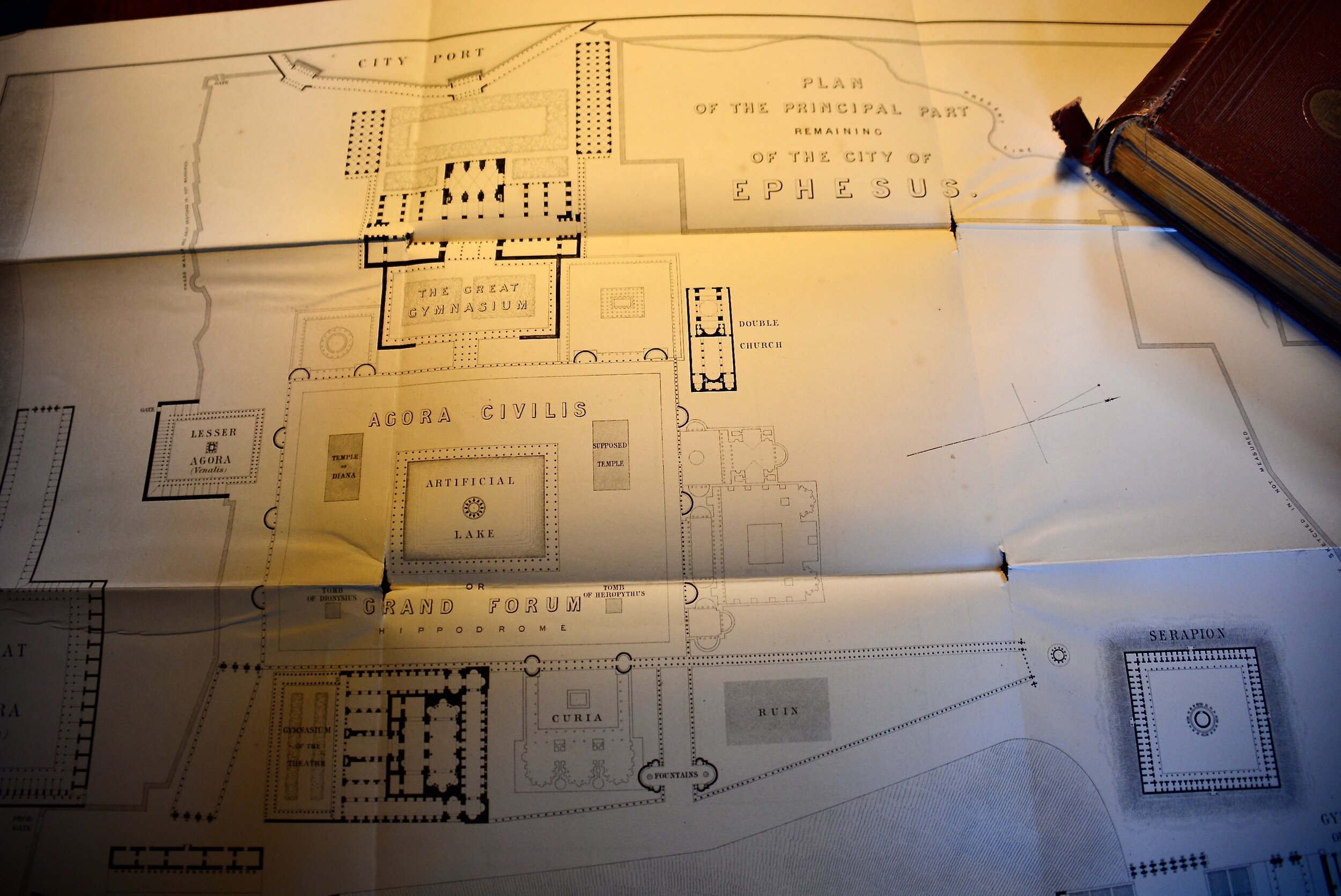

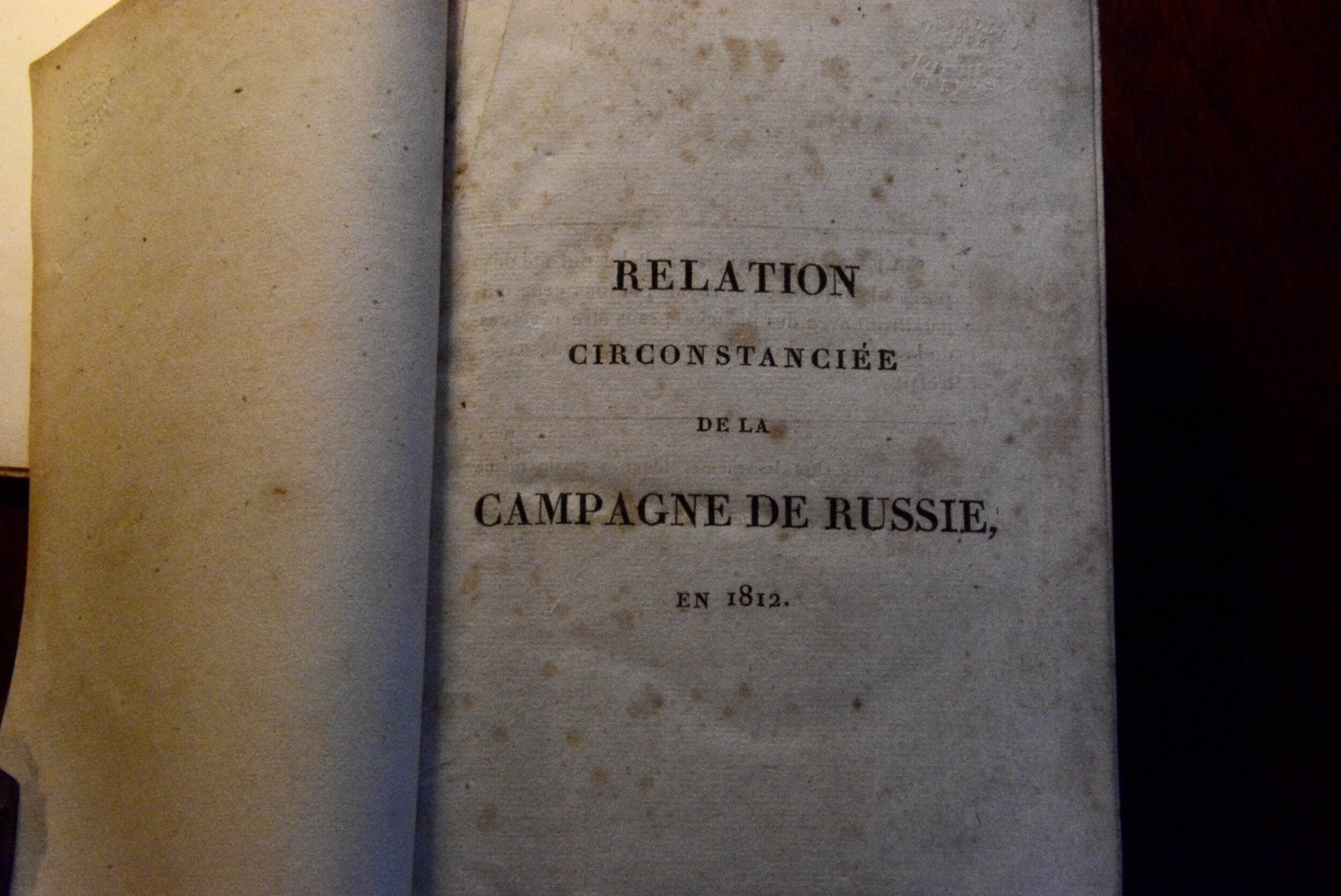

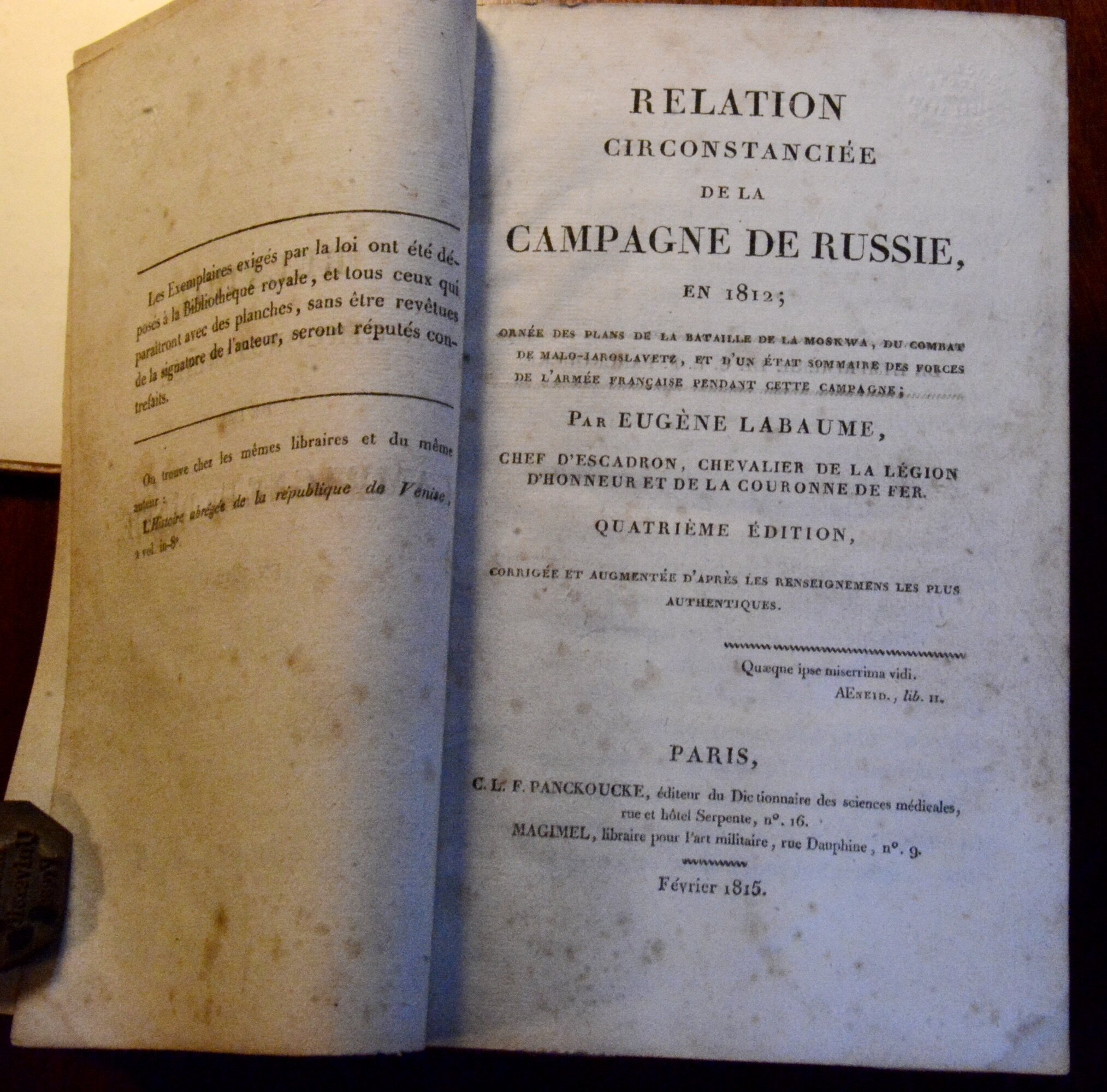

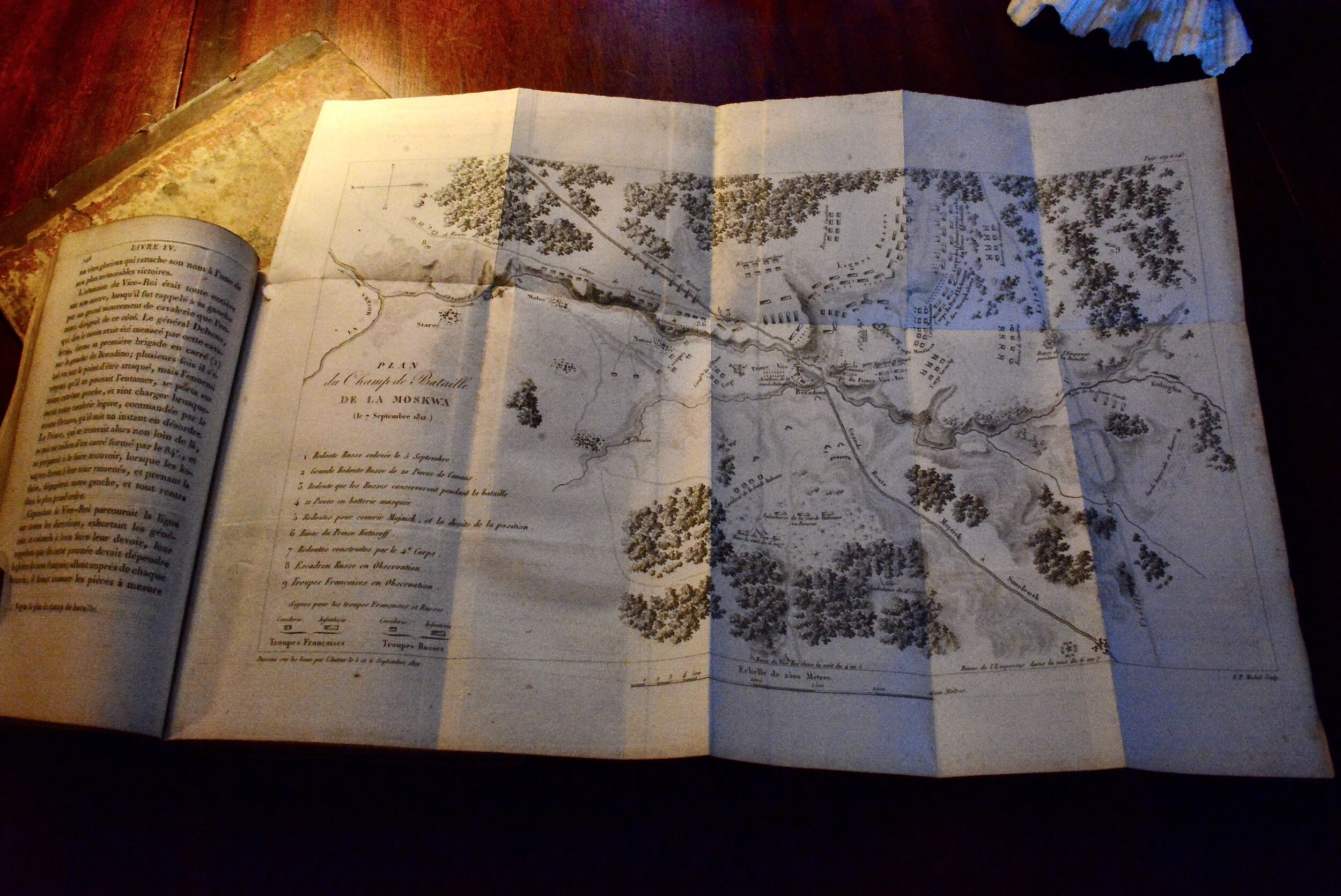

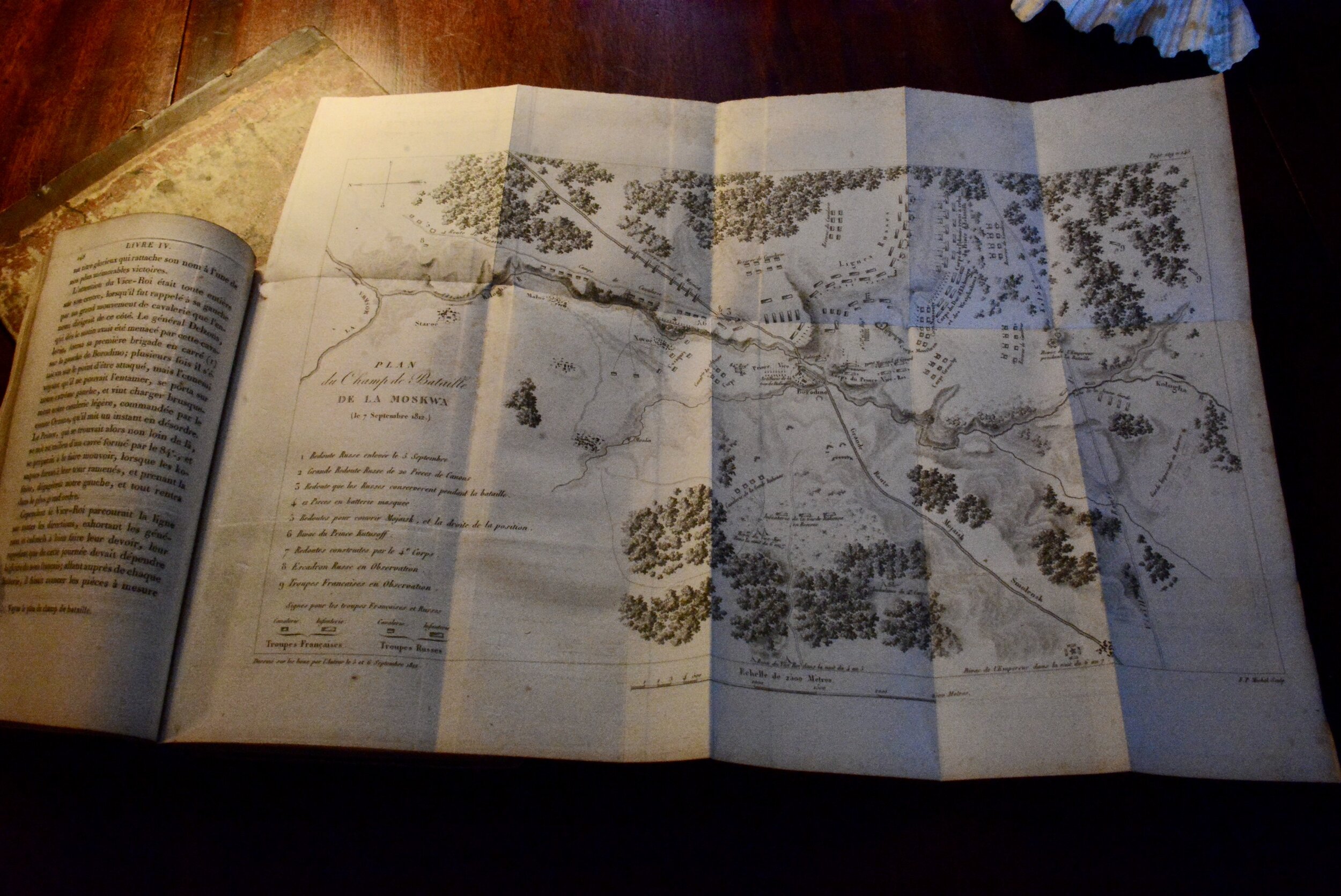

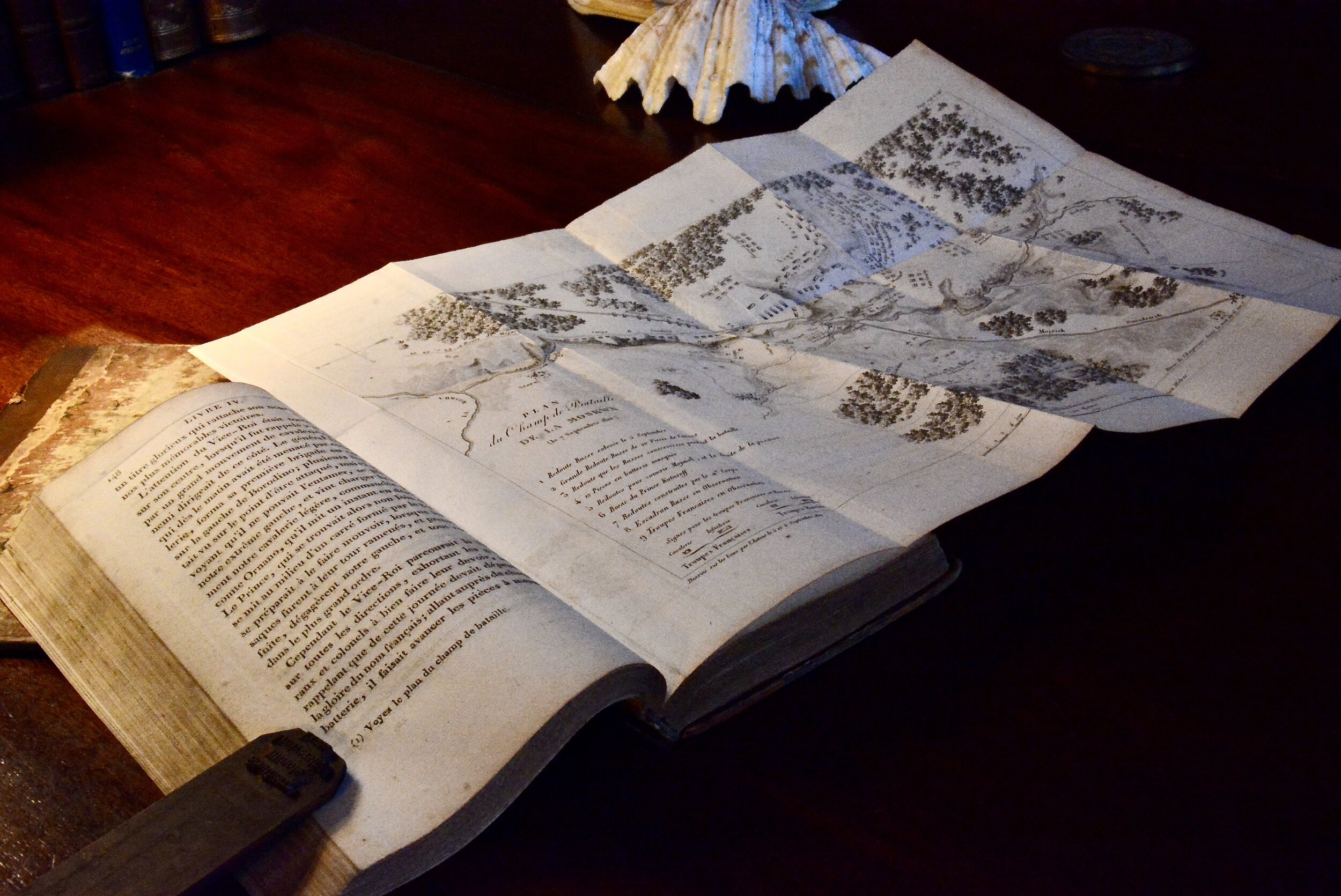

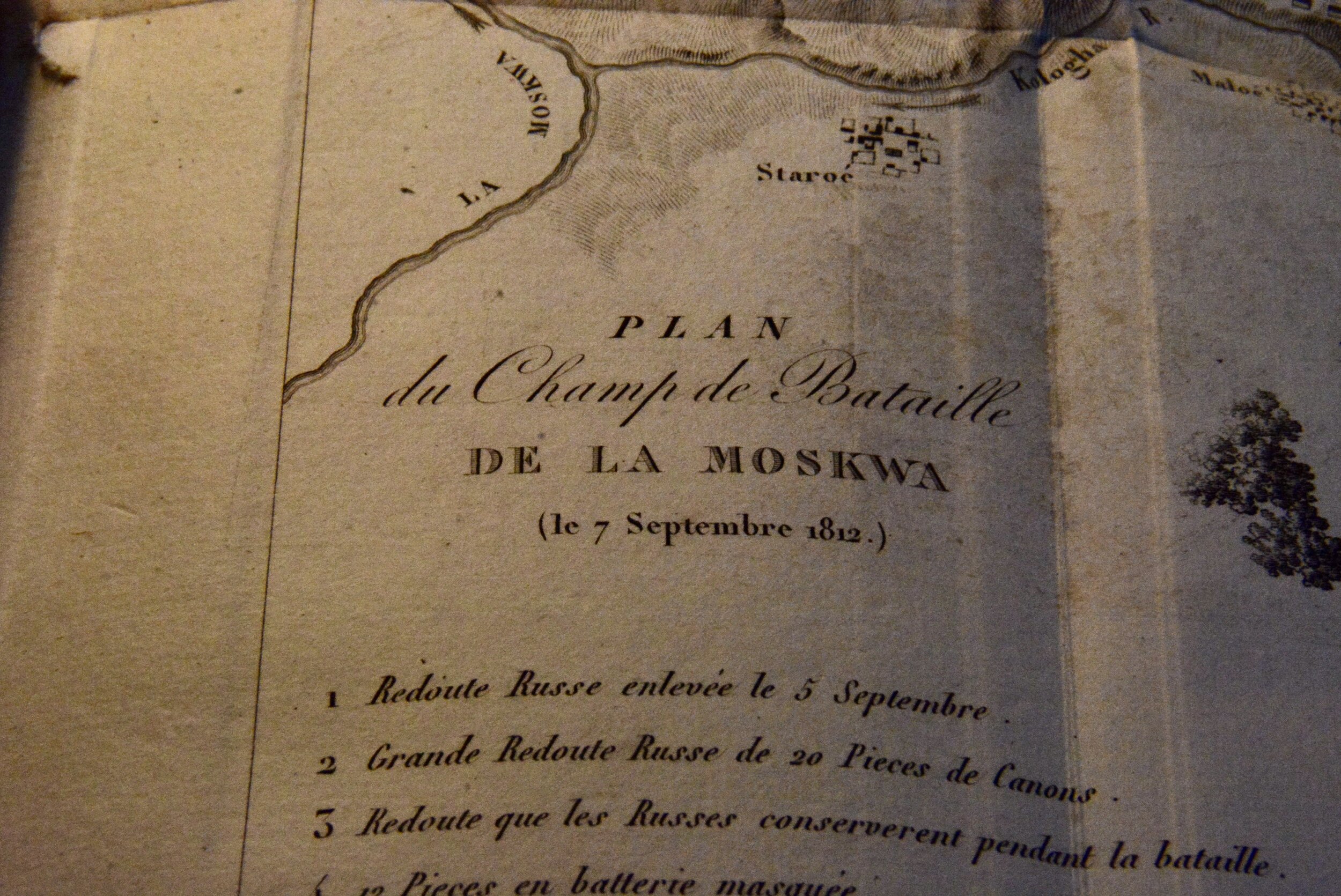

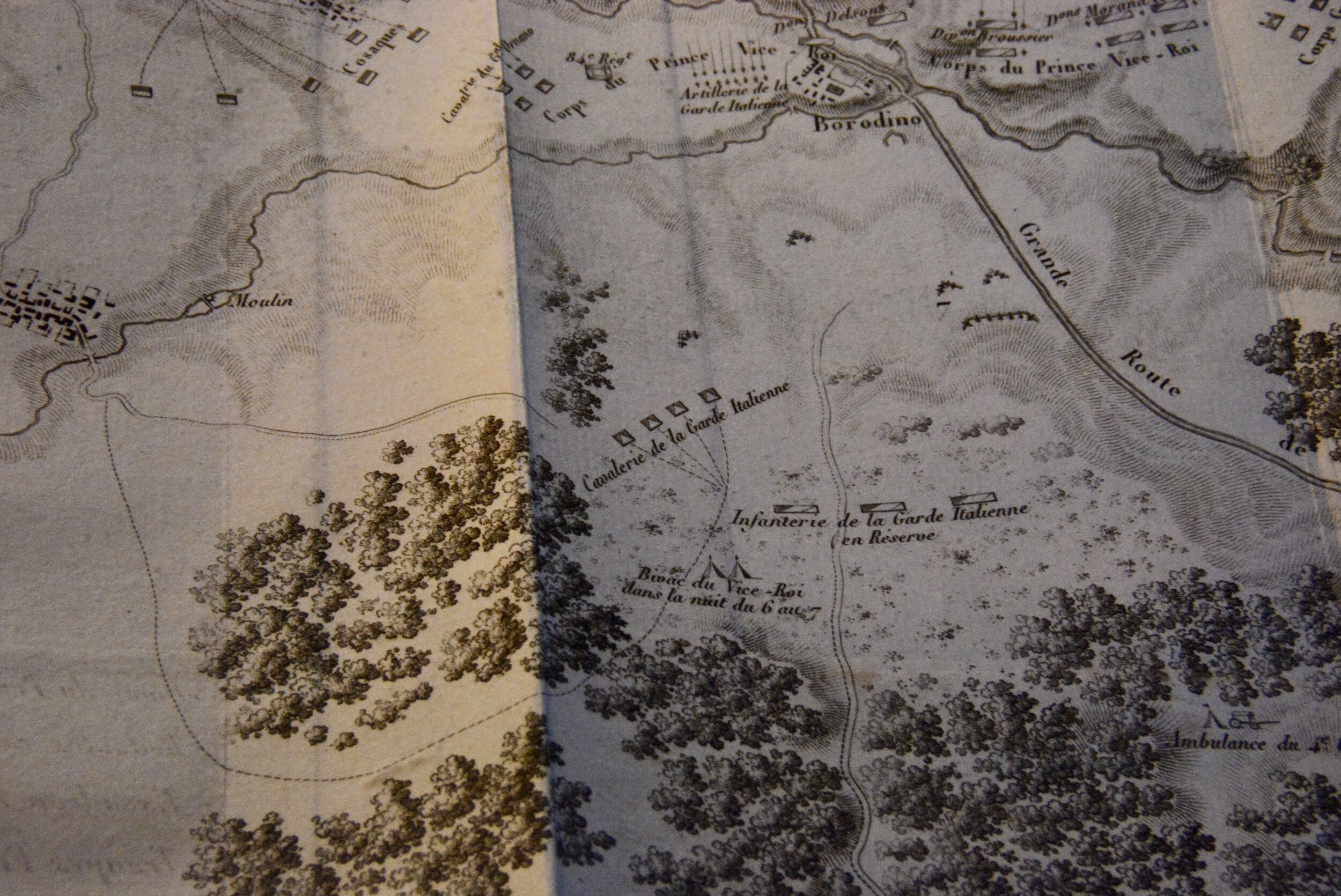

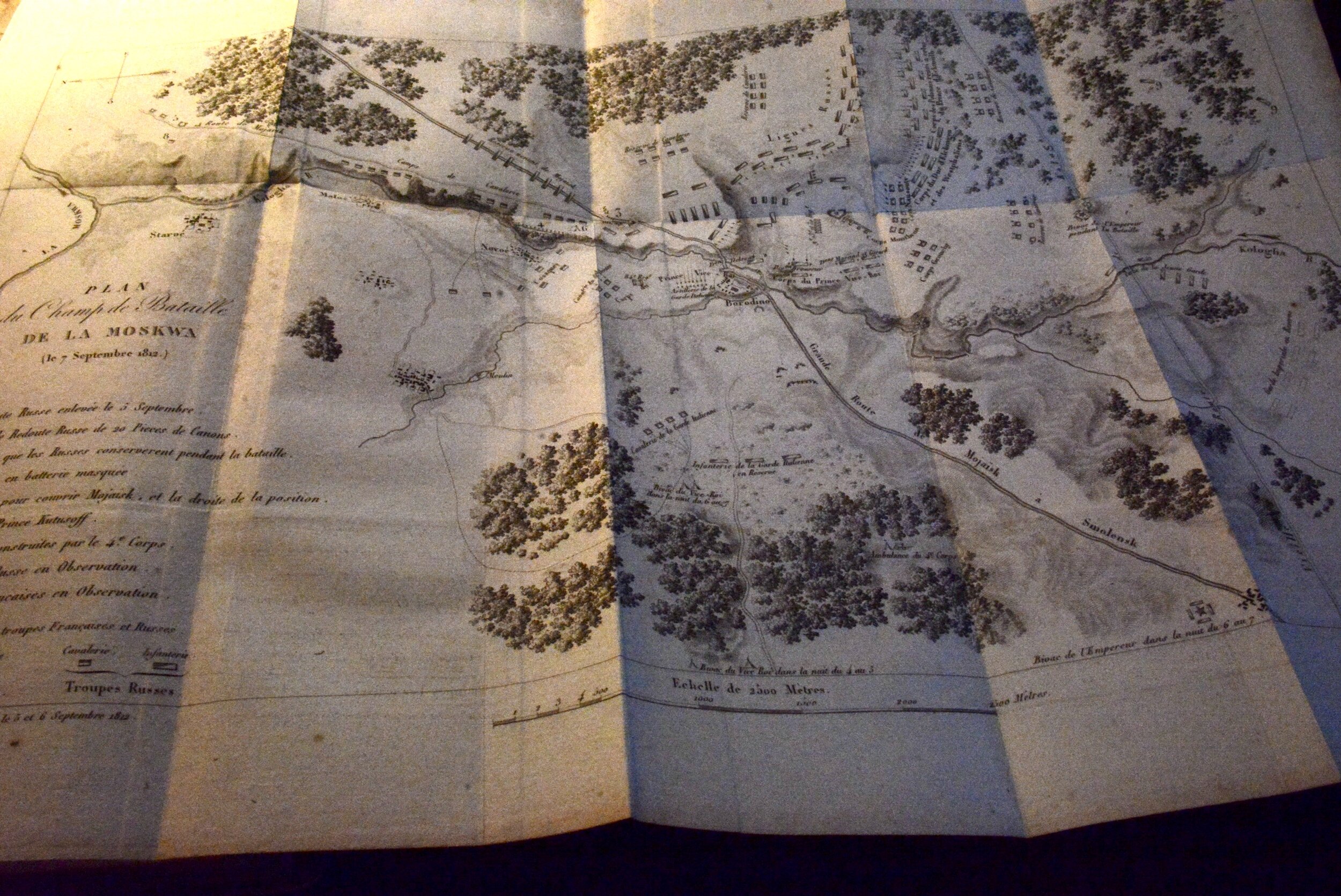

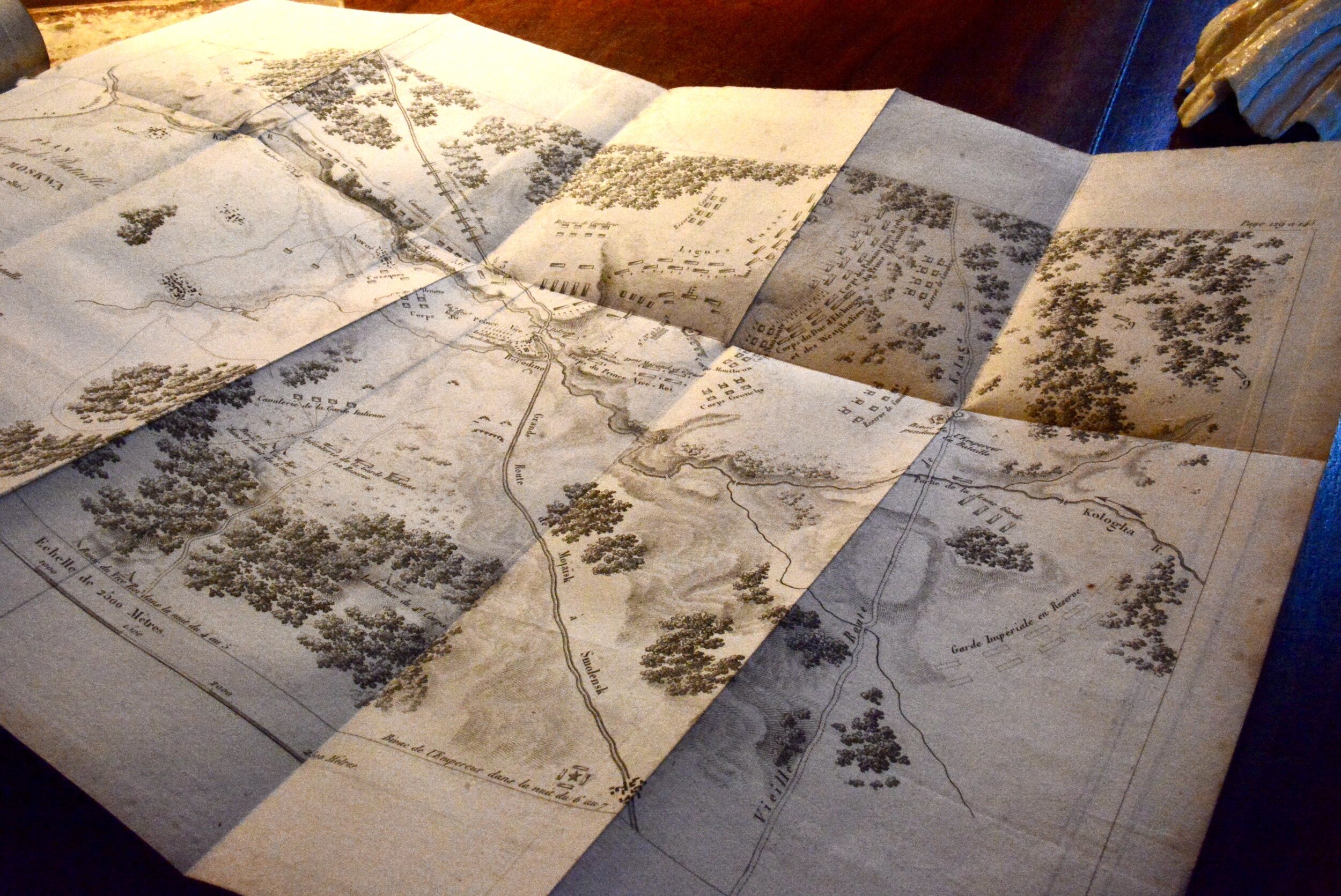

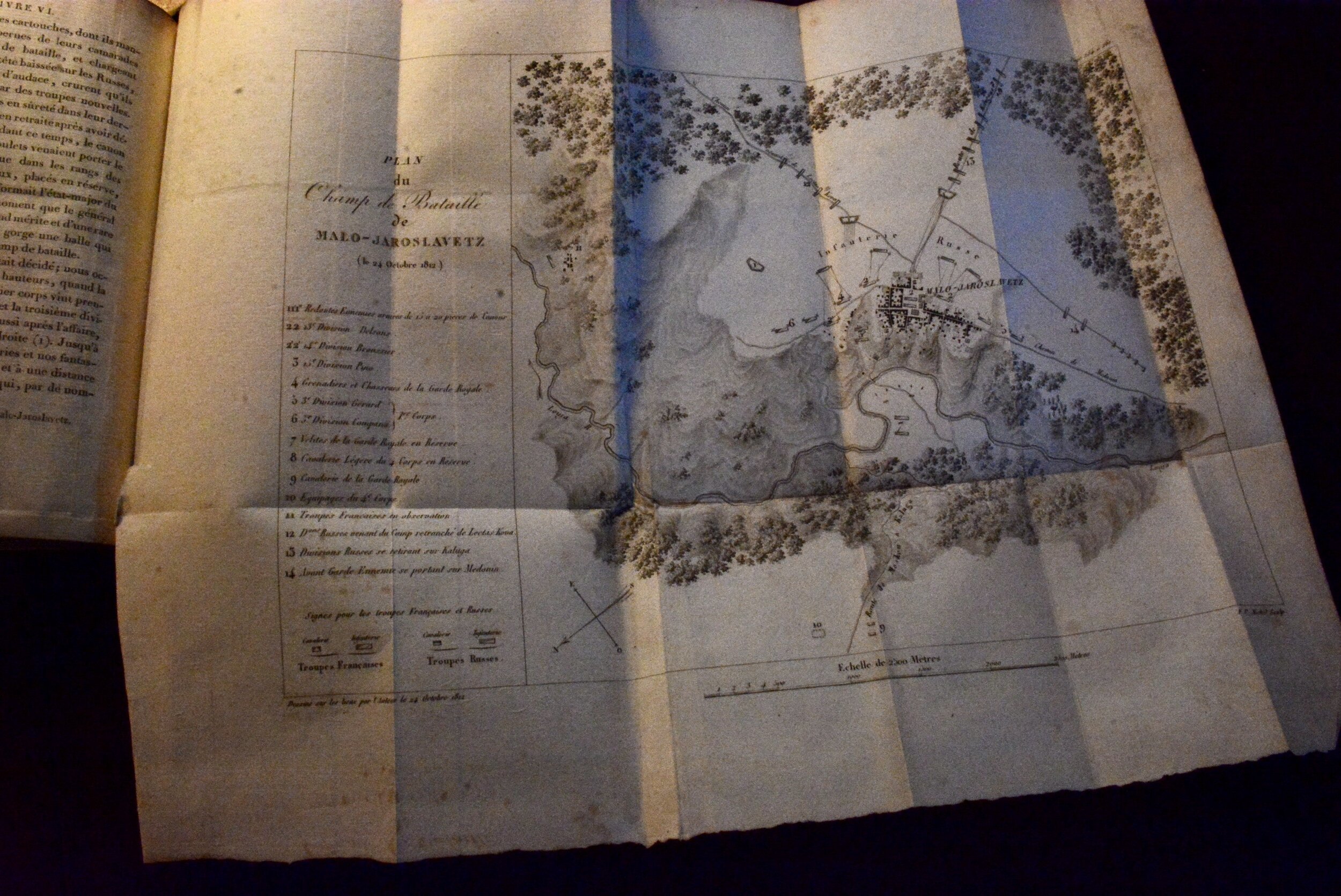

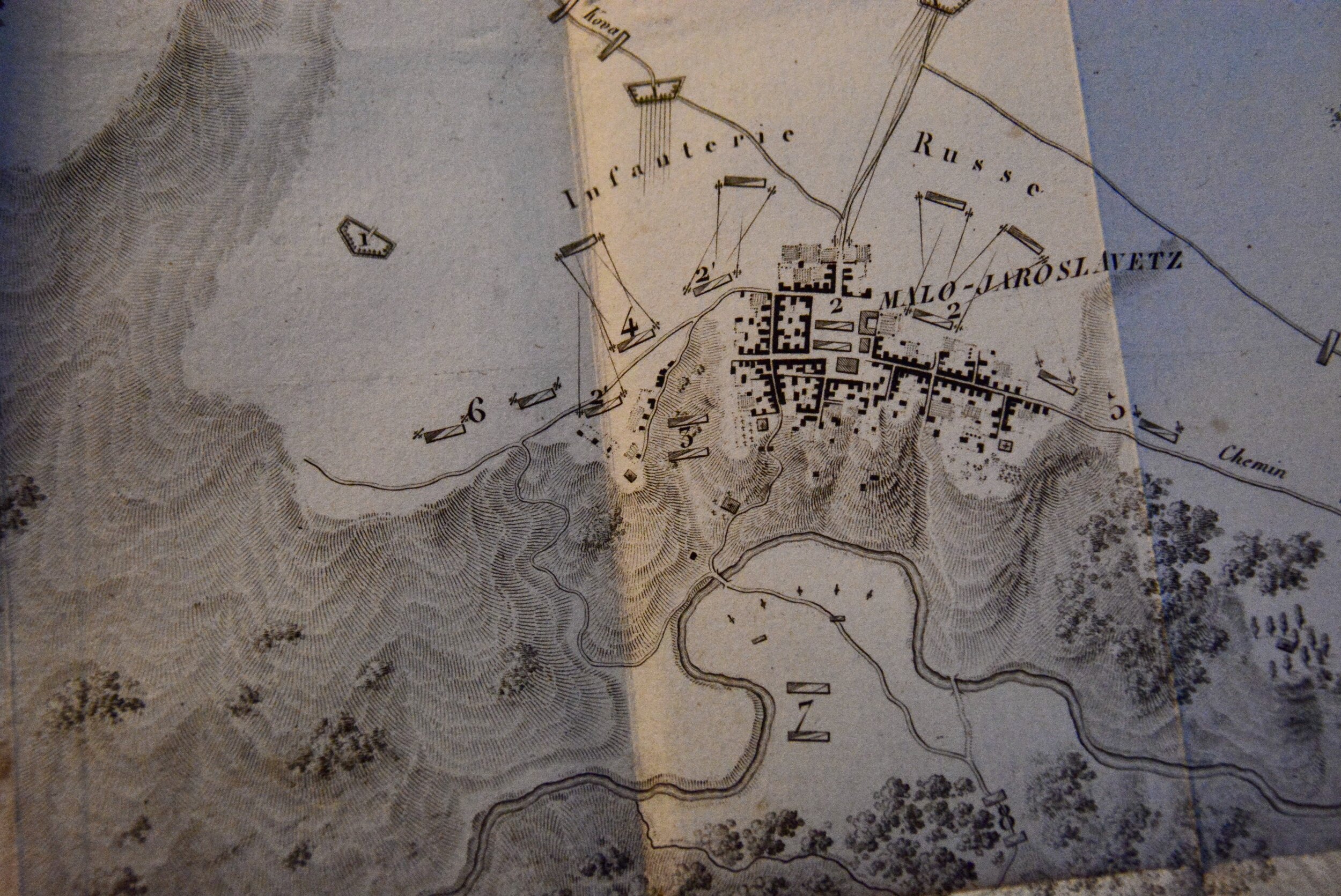

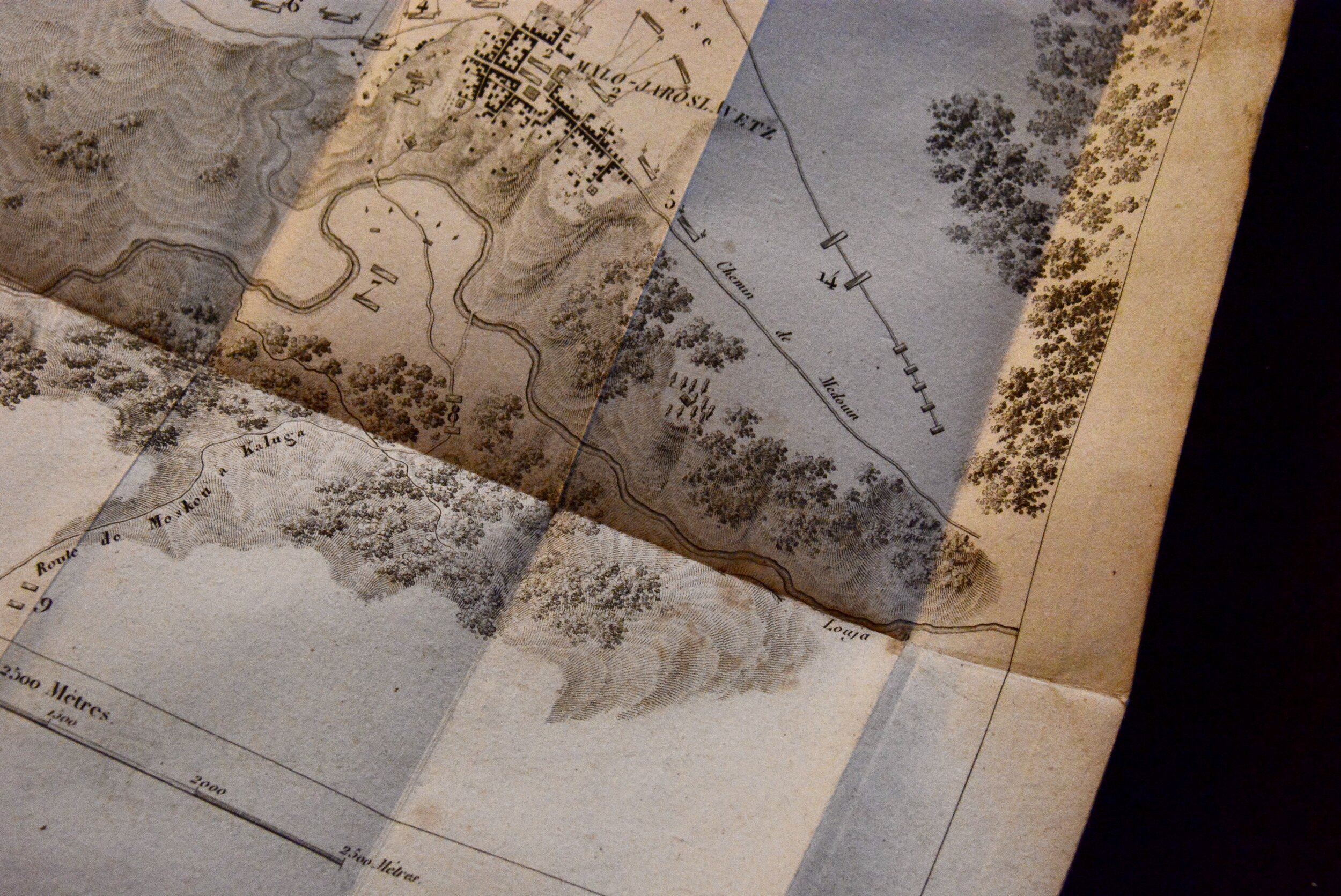

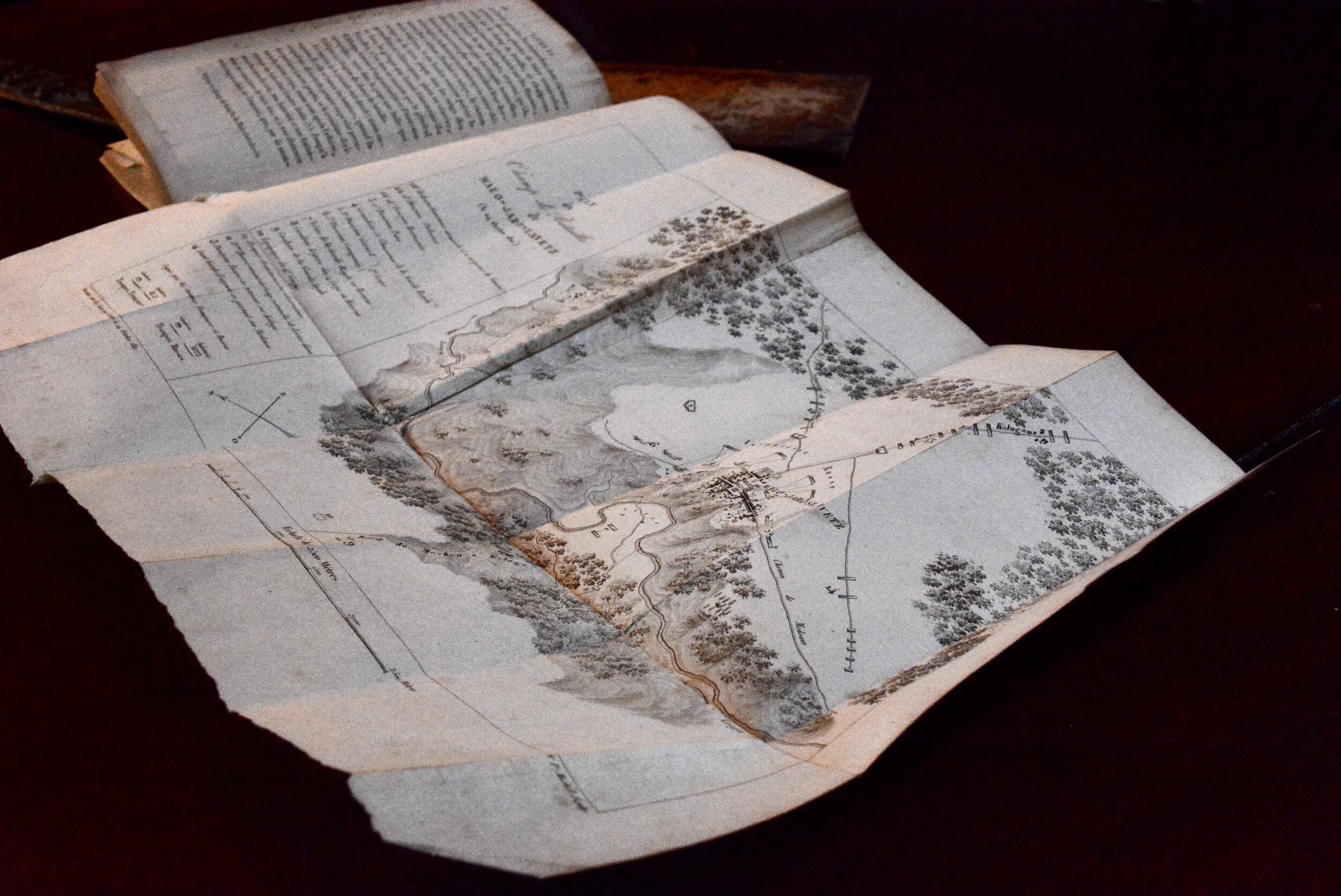

But while assessing some books for listing I ran into several with large fold out maps. Among them Relation Circonstanciée de la Campagne de Russie 1812, a French history of Napoleon’s ill-fated 1812 invasion of Russia, Edward Falkener’s 1862 work on the Temple of Diana at Ephesus, and Samuel Parker’s 1838 Exploring Tour Beyond the Rockies, recounting his travels to the Oregon Territory.

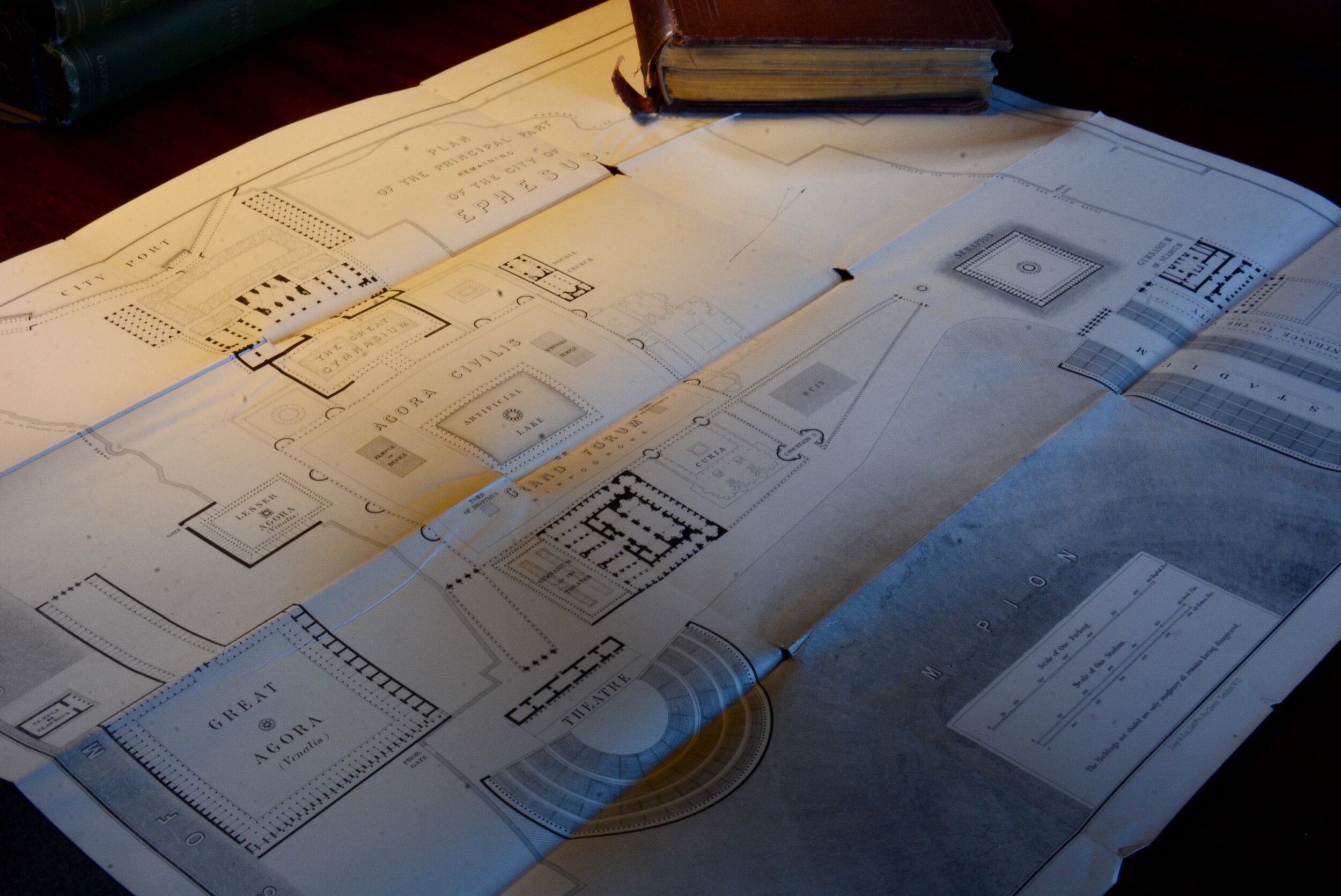

Old books with maps and charts are interesting. One on hand they send you further down the rabbit hole looking for meaning, history, accuracy, and context. On the other hand the they add another layer to the question of the book’s value; their folds, creases, different methods of insertion and placements almost always lead to questions about the book’s condition. They are often missing altogether.

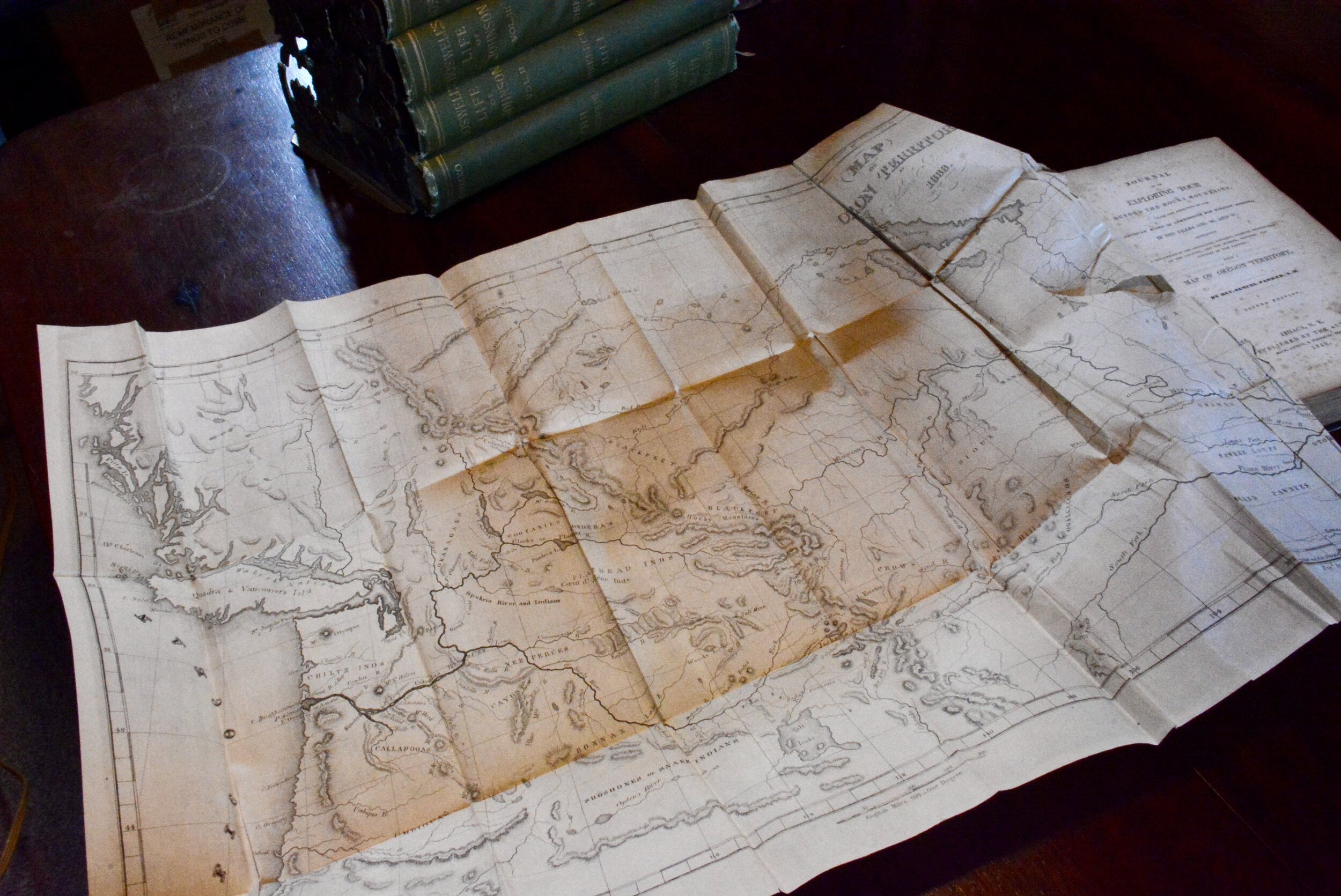

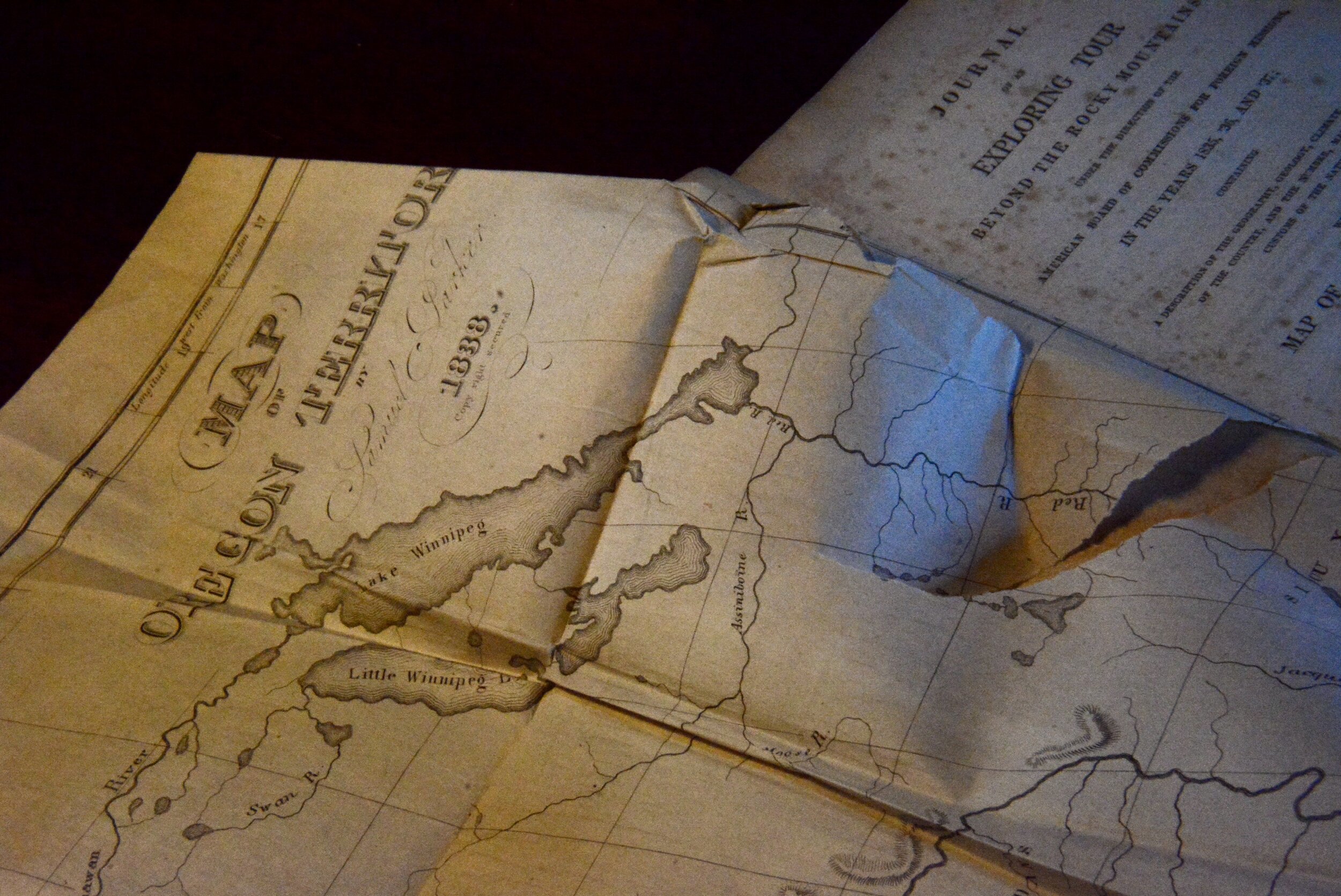

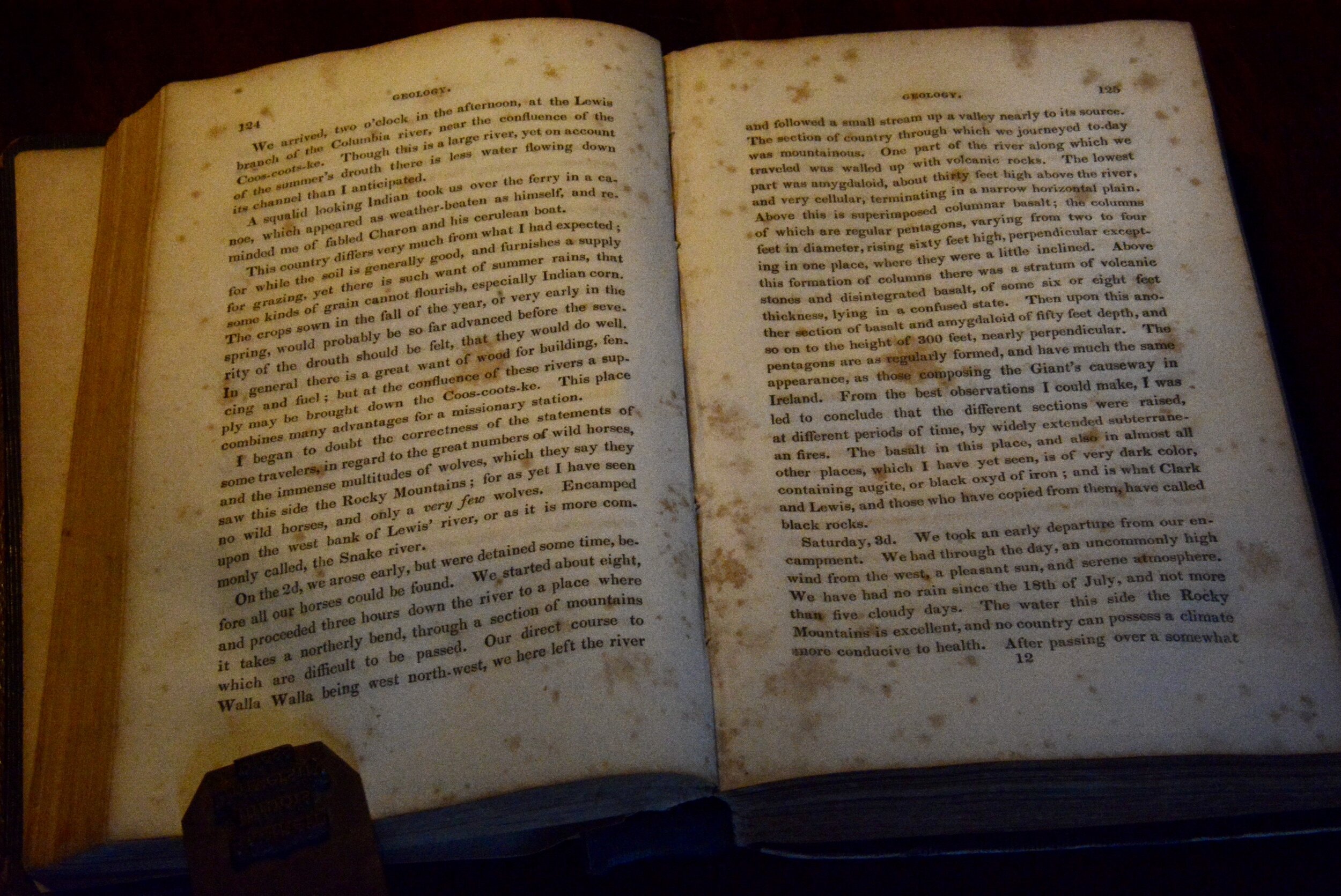

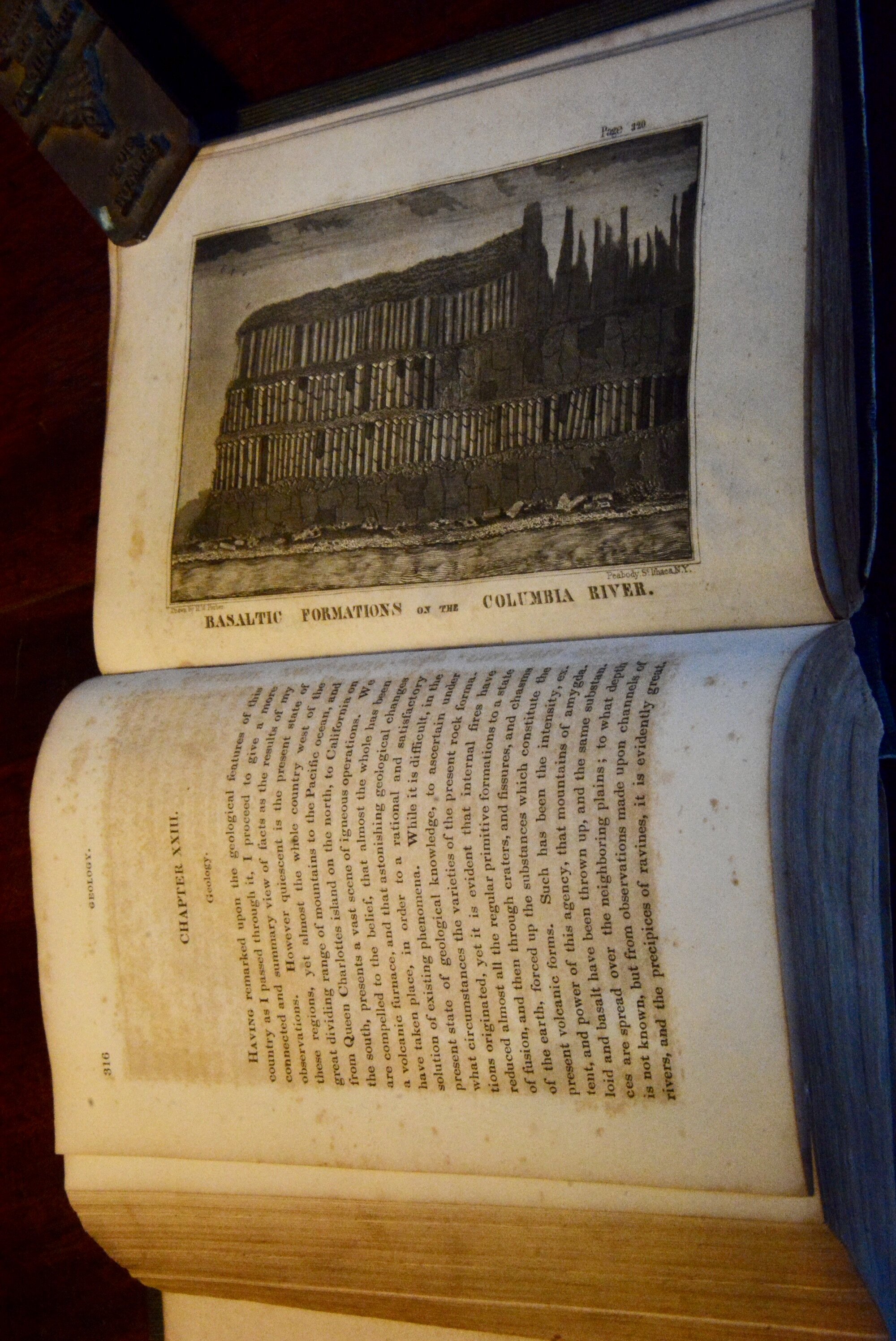

The map accompanying the last is reputed to be the first reliable map of the interior of Oregon territory. Parker was on a religious mission pursuing locations, and presumably people to bring into his particular fold. According to the Washington State University digital library site which contains an online version of the map, “In 1834, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions appointed Rev. Samuel Parker to go to the Oregon Territory and scout locations for missions there. Parker traveled overland to Oregon in 1835, and traveled as far north as Colville while locating sites for missions near Spokane, Lewiston, and Walla Walla. Eventually, he traveled to Fort Vancouver, and from their obtained free passage by ship to Hawaii, and after some delay there he returned to Boston via Cape Horn. In 1838, he published this map, and the book from which it was taken, as an aid and inducement to future settlers.” The Wikipedia entry on the ABCFM is fascinating.

This map is reputed to be the earliest reliable map of the interior of the Oregon Territory. Folds in the map and its insertion within the text are points where—over its nearly two centuries on the planet—weakness and small tears have developed.

The description of this map as the “earliest reliable source, made from personal observation” is attributed to The Plains and the Rockies: A Critical Bibliography of Exploration, Adventure and Travel in the American West, 1800-1865, begun by Henry R. Wagner and continued by Charles L. Camp and Robert H. Becker. Book and map sellers most often refer to this source as “Wagner-Camp.”

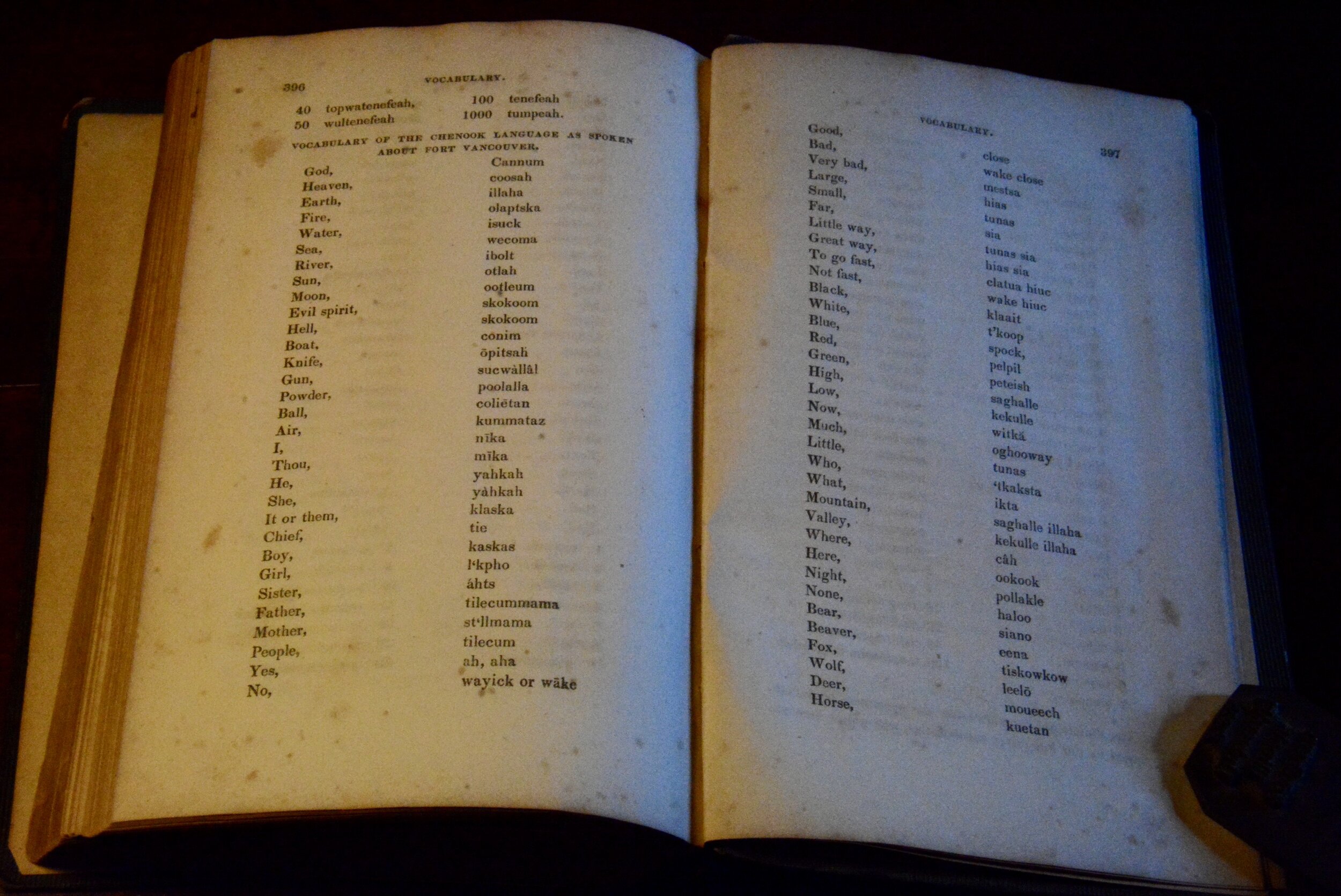

In addition to its map the book contains a glossary of native terminology with English equivalents, and various climatological data.

Click images for a Slideshow

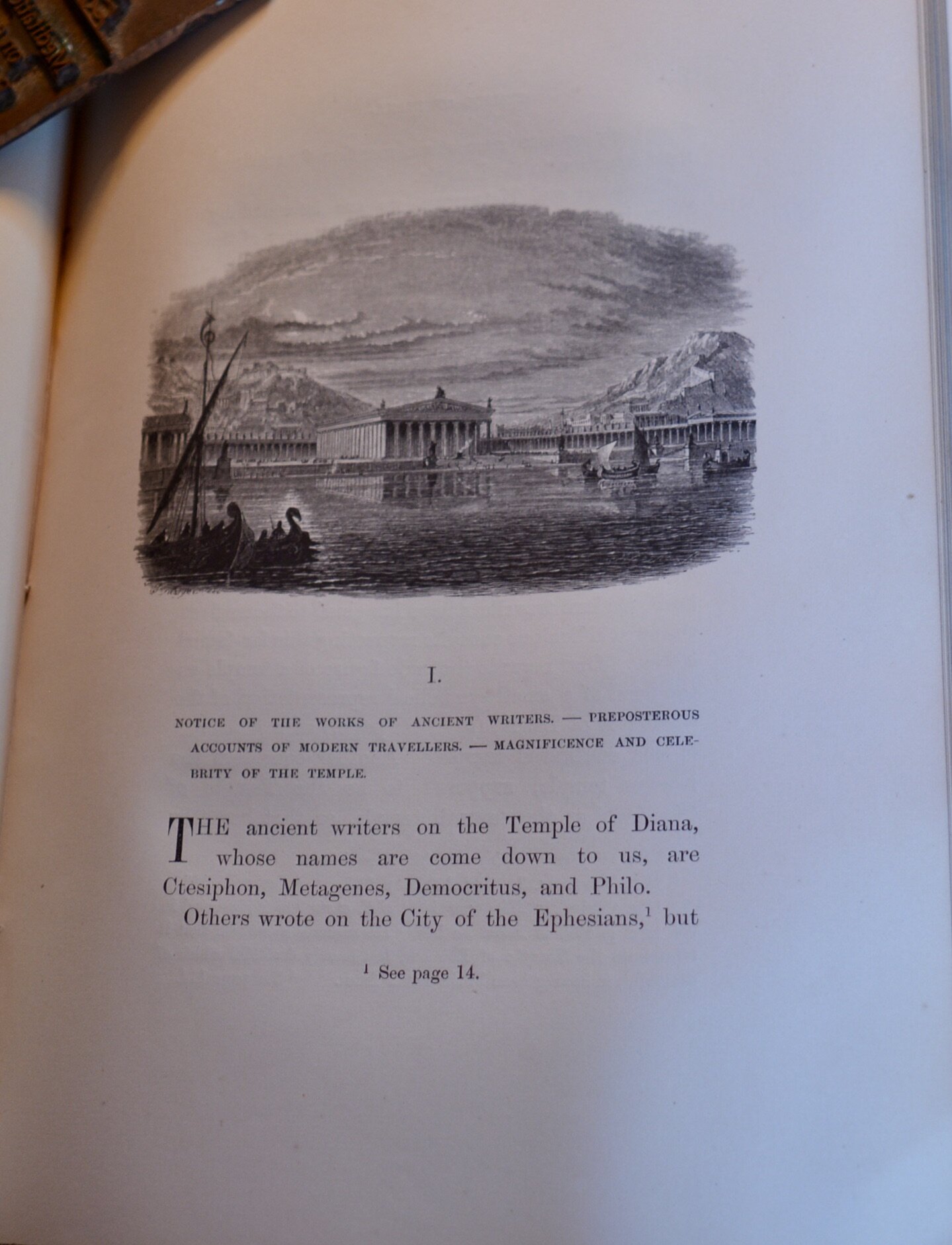

Falkener, was a drawer, artist, and draftsman so his work, The Temple of Diana at Ephesus, is notable not just for its large fold-out map, and many smaller interior maps, but for its colored plates. They are the equivalent of a current architect’s renderings with scenes of the archeological sites as imagined in their day, beautiful and detailed.

The Temple of Diana as a name for the structure itself is no longer in favor. Wikipedia’s page on the Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, notes that it is less precisely known as the Temple of Diana; Diana was the Roman equivalent of the name Artemis

Both the colored plates and the maps and other schematics from Falkener’s work are frequently reproduced and available for sale through various reprint services. At least one of the plates even shows up on a tee-shirt. All of this makes my efforts at photographing the plates carefully—I didn’t want to use the scanner for fear of further damaging the brittle binding—seem vaguely pointless.

Slideshow

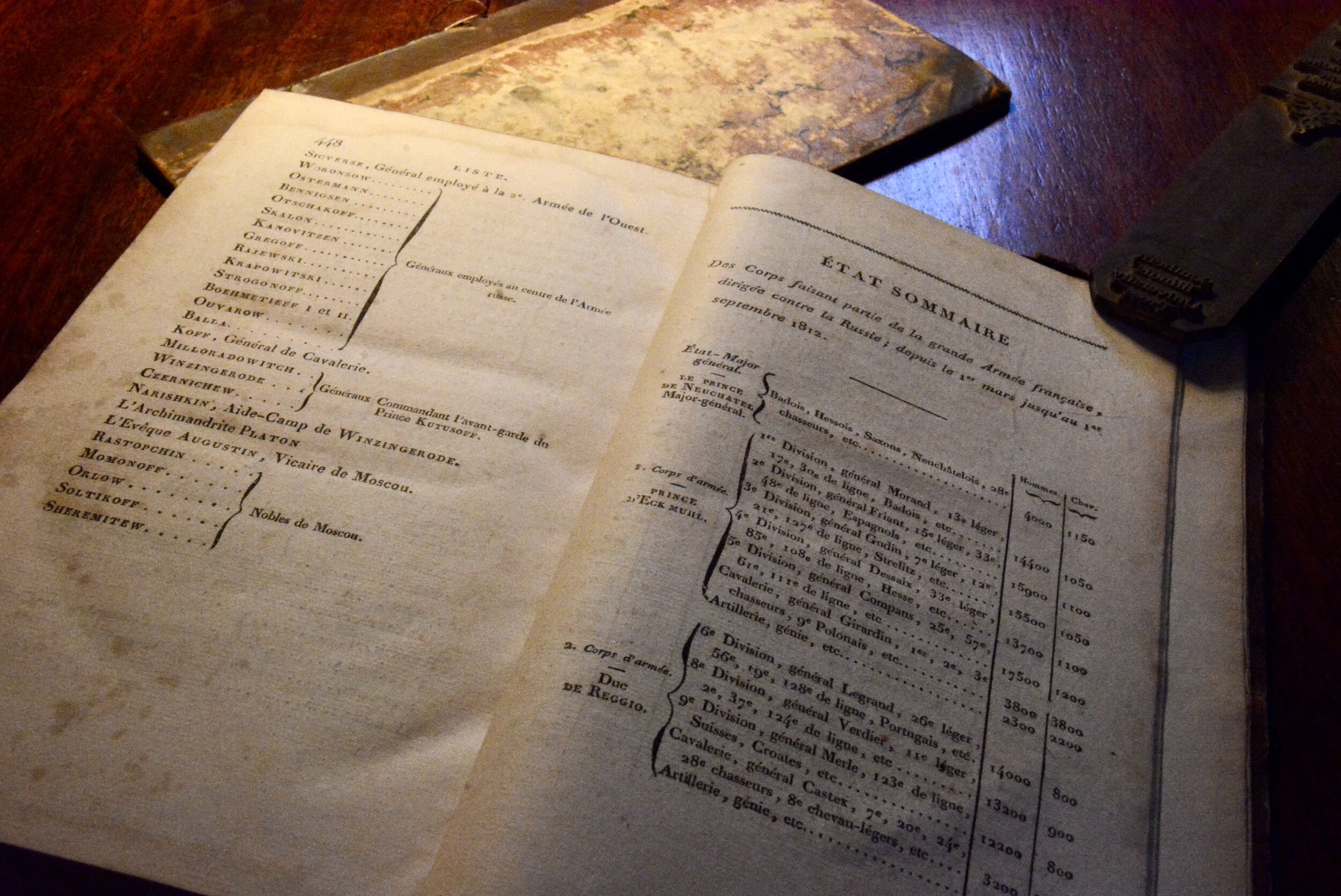

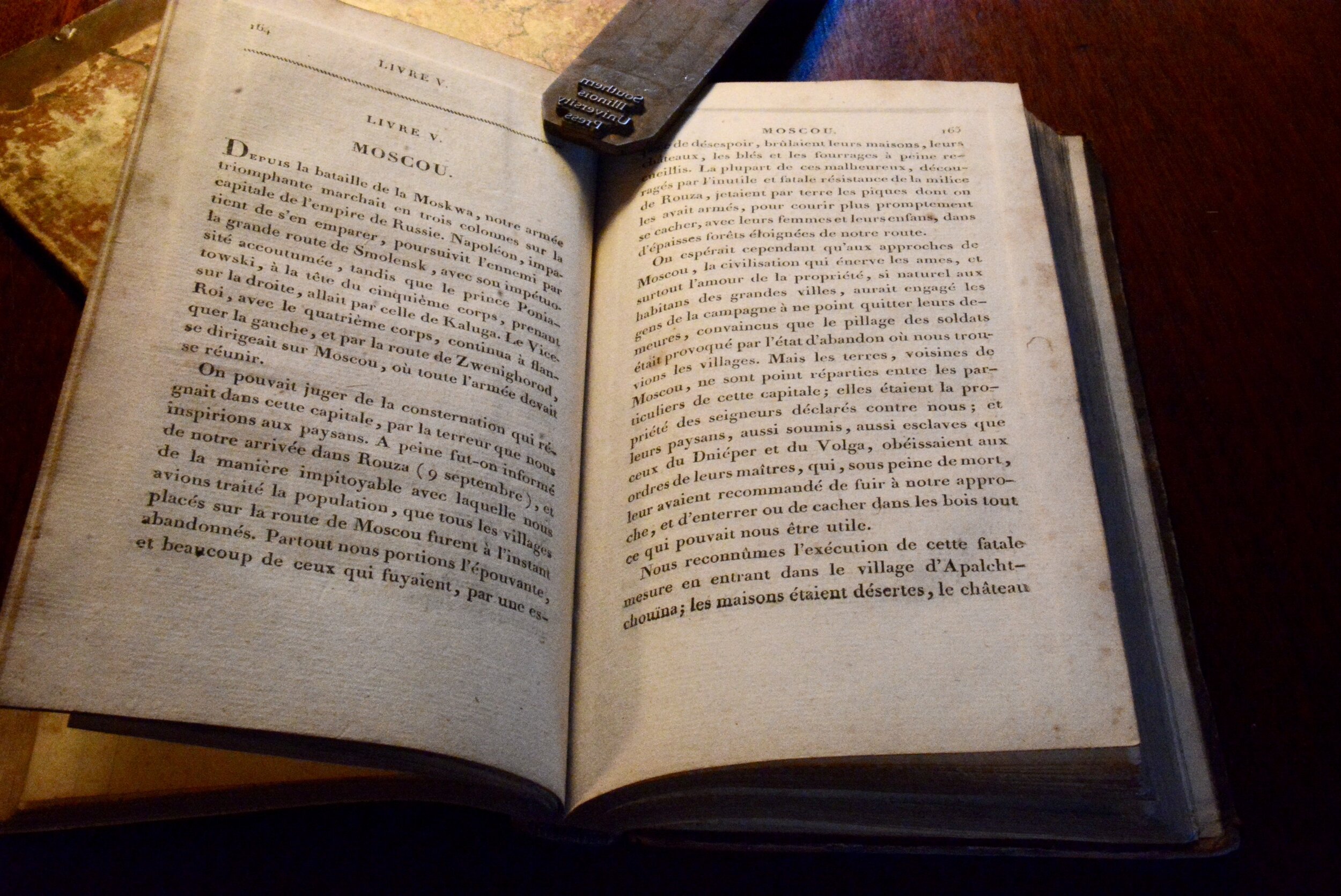

Campagne de Russie 1812, in addition to its maps, is filled with data. The work was obviously popular in its time as even my rudimentary French told me this February 1815 edition was the fourth edition of the work. It also suggested further research in english. As I plowed through the Wikipedia entries on Napoleon’s reckless caper to Moscow, I was first astonished by the apparent irrationality of the campaign: Wikipedia suggests the reason for the campaign against Russia was to stop the Russians from trading with the English which in turn would make his simultaneous war with England a little easier.

My second realization was that most of what I know of the Napoleonic Wars, and the American War of 1812, I learned from historical fiction, notably the sea-faring novels of Patrick O”Brian. As a result, with the exception of the Battle of Waterloo, burned forever into my nine year old consciousness by the brutal battle scenes depicted in Sergei Bondarchuk’s Waterloo during an ill-advised childhood trip to Portland Maine’s State Theatre, I know mainly about the naval engagements of the wars rather than the political intrigues and land based battles.

Slideshow

It is a long way to Moscow

I know about Nelson and the Nile. I know about blockades at Toulon and Brest. I know about Gibraltar, still shimmering in my mind from the one time I actually laid eyes upon it—late at night in 1960s while passing it in the Italian liner Raffaello. And I know about the USS Constitution and its taking of the British frigate Java. In The Fortunes of War O’Brian’s primary character, Capatin Jack Aubrey, was conveniently placed as a guest onboard Java at the time of the battle. And of course I catch a quick view of it off my left shoulder when headed to Boston.

And now, thanks to my travels down the rare book rabbit hole, I know that Wellington’s English and Bluecher’ s Prussians were not the only ones to defeat Napoleon.

Relation Circonstanciée de la Campagne de Russie 1812, a French history of Napoleon’s ill-fated 1812 invasion of Russia. $88 AbeBooks.

Edward Falkener’s 1862 work on the Temple of Diana at Ephesus. $88 Abebooks.

Samuel Parker’s 1838 Exploring Tour Beyond the Rockies, recounting his travels to the Oregon Territory. $88 Abebooks. (SOLD)