I knew that I would miss him.

But I thought it would be an emotional thing, a tugging or a regret that perhaps I hadn’t held up my end. After all he had been there all along. I could not remember before him. What I did remember was that he was big and strong and solid even when I was just a child. I had known him well for nearly sixty years.

But I missed him immediately. It wasn’t subtle.

The following day the west side of the house a was blinding debilitating glare, its windows now a hideous basin of reflectivity. The formerly breezy second floor bathroom, once a retreat, was a stifling cauldron. Where evening western light had once filtered its way through the broad lower branches of his canopy before reaching our kitchen it now had time to coalesce in the side yard after emerging from behind the neighbors’s trees and blast through the window to waste my retina with thrombotic fury.

Linoleum, long held in place by the syrupy dampness of its decaying underlay immediately began to peel back at the seams. Plaster, freed from the gravitational pull of its moist surface, began to flake like the forehead of a pensioner.

What had I done?

The decision had been delayed for years. Each spring new translucent greenery appeared on fewer and fewer of his upper branches. Wincing I would turn away, as one does from recurrent doddering patter: I tried to find something else to think about until the awkwardness passed. A hammock purchased during the lockdown phase of the Covid pandemic only made things worse. Lying on my back I would be confronted by his crown looking like a patchy scalp.

But stick season would return—like spring in reverse—and bring plenty of companionship to the deadwood around his ears and buy me another five or six months of complacency.

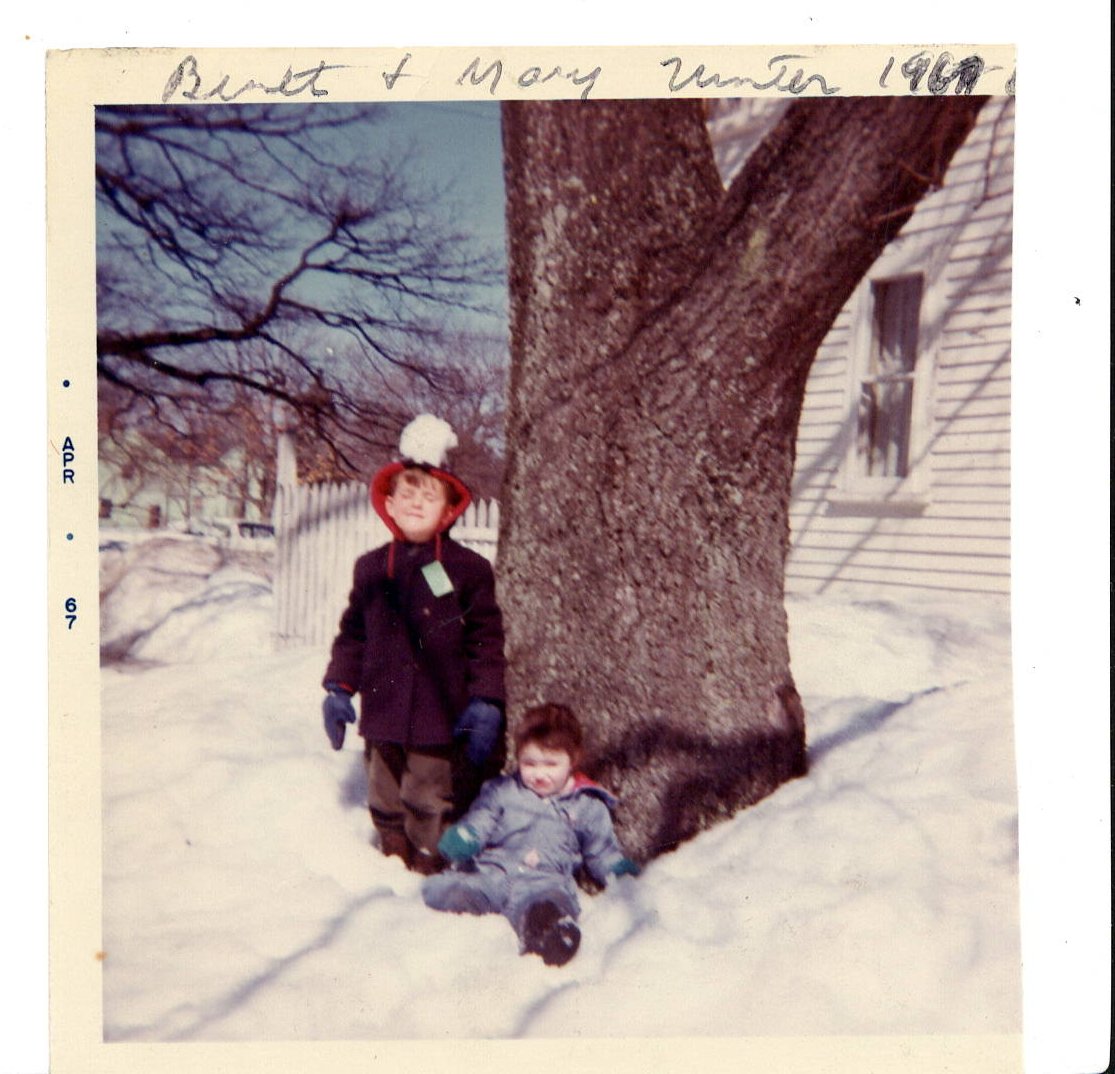

Here he is in the winter of 1967, probably seventy years old, or so, at the time. I am adorned by the snowball, my sister Mary, not yet three years old, sits in the snow. At this age, with the help of a ladder, or an old black Raleigh three-speed leaned against his trunk, getting to that vee and then working my way gradually up the right-hand stem was a possibility. Within a few years, with the help of a couple of burls and stronger hands, getting to the vee unaided was possible but challenging.

Ironically, another Oak on the east side had been bothering me for years. I could see the squirrels coming and going from an ample gap at its base. In 2014 the east oak was missing bark on a patch a foot or so wide and stretching up to my waist like a brutish stretch of varicose veins running up a calf from a swollen ankle. Squirrels exiting at its scarred base left trails, like Pigpen, of what looked like a cloud of sawdust.

Then there was the hen of the woods. Some sort of mushroom the hippies like was drawing crowds. My reading in the front room would be disturbed by abrupt braking by the bend in the road. The slam of a car door, motor still running, signaled a new visitor. Another wooly headed character would be fussing around at the base of my oak, looking furtively this way and that. Not wanting to discuss religion, or worse spirituality, I would keep a low profile until the Prius moved on.

This began to happen with some regularity. Eventually—this was back in 2014—I checked in with a friend, the owner of a local cycle shop. His Facebook stream was often a source of mycological tips and advice. “Yeah….your hen,” he has a way of drawing out the first part of a word as if whatever followed may be confidential. “People have been talking about your place, wondering if you’re going to harvest it. They’re worried about insect damage.” Within a matter of hours, through the good offices of the cycle shop, my hen of the woods was removed.

The visitors stopped but I learned that tradition holds that the hen’s appearance foretold sphacelation in the base of my tree.

So I called the tree guy.

Same tree guy my father had always called. And then I called again, and again. I did get a call back one day—he said he’d be around soon. As soon move along the years I called again. Eventually Tree Guy Number One did stop by. Driving by, he made the mistake of meeting my eyes while I did some side yard chore. Having no clear evasive path, he stopped and with a sheepish expression said he knew he owed me a call. But still, no action was to be taken on my tree. He did peal back a long swatch of bark and throw it in the grass. I also heard lengthy remarks on how bad one of my sisters’s neighbor’s oaks was. It required the full court press. My tree, housing a menagerie and sprouting fungal wonders, could just stand there.

After all, it had stood on this side of my house a long time.

I finally moved on to another tree guy. Tree Guy Number Two had a daughter in my boy’s class but was reputed to be a touch on the pricey side. But he returned the call promptly and came over at the appointed hour. He held clip board and some sort of gadget, which gave me confidence. He thumped on the trunk for a bit and pealed off a long swatch of bark which he dropped in the grass. They all do this.

I was not to worry about the squirrels. I may have learned that if the oak was to fall, its expected path would not be through my roof, or through the neighbors driveway to smash his vintage Buick Electra. Its expected path was out into the street. So, so long as no one was there, all would be well. I may have inferred the last bit. I also learned that some of the mycological traditionalists can conflate correlation with causation.

Either way, for now that tree would stay. Tree Guy Number Two’s assessment seemed fact based and had involved some sort of analysis. And it always gives you confidence when someone declines an offer to be paid for services because in their opinion the service isn’t necessary. Tree Guy Two affirmed Tree Guy Number One’s recalcitrance with a rationale that I could comprehend.

Even now, another decade on, Tree Guy Number two’s assessment of my easterly oak still stands.

But the easterly oak never had the same emotional pull as the westerly tree. It’s right on the boundary; in fact over the years it has cleaved the boundary line laid out a hundred and twenty years ago with marble scavenged from some demolition project at the college where the first owner of my house had worked. Always with one foot in the neighbor’s yard, this oak wasn’t really a part of the family. Its trunk, straight and branchless until above the roofline, offered nothing to a young scrambler. Even its leaves end up in the neighbors’ yard. You saw it as you looked at the house from a distance, but from within the house you looked past it.

The shadow on the western wall of the house shows how tall he was even in 1923. The horse, who once lived in my barn, is Phil. In the wagon are Catherine Johnson, who sold the house to my parents in 1952, and Arthur and Maisie Wheeler. All are relations of my fifth grade teacher, the source of this photo. Catherine’s husband, John Franklin Johnson, moved the core of the house from the lot on the corner of Boody and Maine Streets where 260 Maine Street now stands. Frank Johnson got the house from the estate of Rebecca Packard and moved it around 1905. The house is believed to have been built—at Maine and Boody—around 1857 and occupied by the Packard family. It was damaged by fire sometime before the move. Interestingly the first “Town House” was also located near the corner of Maine and Boody, it was destroyed by fire in 1857. In my childhood an oval sign stood on that lot commemorating the first Town House.

The age of the trees is always a question. A good bet is that they went in around 1905. I got the 1923 photo in an indirect route from my fifth grade teacher who, as it happens, was the grandchild of the man who had moved a good portion of my house a few blocks from over by the college. Mr. Johnson was a factotum of some sort at the college and got the house from the estate of a Mrs. Rebecca Packard.

My fifth grade teacher, Mary, who still lives in my neighborhood, had spent a good deal of her youth on Longfellow Avenue in the home of her grandmother, Catherine, who sold this house to my parents in 1952. Mary had heard stories of the house, and the horses—Phil and Major—who had lived in the barn. These tales illuminated her childhood the way scrambling up the western oak illuminated mine. Not long after I bought the house from my father my old teacher rang me up. She badly wanted to see inside the house, to look around the rooms she’d heard about, to see inside the barn where the horse stories grew. She had been reluctant to pester my parents knowing they were older and not having the direct connection she had to me. She had photos she wanted to give me and stories to share. She could tell me the horses names and what each was known for.

I have had the 1923 photo for close to twenty years now, but the shadow of the oak, the one on the west side, the guardian, was something I fell to just recently.

This past spring, some three years after I put that hammock out back, I came home from work to find orange cones in the street ensconcing a giant chipper parked in front of another neighbor’s house. A procession of oaks that had lined the curbside of his double lot and a handful of trees out back were down. Huge piles of logs filled the gap between the two houses on his property and logs smaller than six inches in diameter were being hustled into the maw of the chipper with Fargo-esque zeal.

Seven trees in all. None of the trees had had the majestic girth of my oak but they were all just as tall. I knew the yard well. I had spent my youth in it; these oaks had provided years worth of ammunition for acorn fights. Instructed to pick the sharp little remains of the style off the ends “so no one gets hurt,” we fired away at each other like Sandy Koufax.

Three thousand dollars my neighbor, David, told me. I asked why. It didn’t seem possible that any of the trees in the side yard would have been a danger to any structures.

“Benny,” he said—no one but David calls me Benny but he has been doing it for nearly sixty years so I let go—“I’m 86, I’m tired of raking leaves and acorns. Can’t do it.” He bemoaned the fee while I thought about my two oaks and imagined I might throw in a string of scraggly white pines on the backline. In a strong wind those pines whip back and forth like seaweed in waves. I’d have gladly gone twice his three thousand to take down the oaks and neaten up the pines.

From above the hammock, August 2023.

I chatted with the foreman for a bit and he explained that if I called the number on the side of the truck one of the girls would set up an appointment. Someone would come out and give me a number. I took a photos of the side of the truck—I didn’t really need to do it because this outfit has more yard signs around town than your average gubernatorial candidate. You can’t run down a street in town without reading the fellow’s name and number on plasticized corrugate.

But I did call the number. A person answered. I told them where I was—right next a big job they had going on now, a $3000 job I emphasized.

Tree Guy Number Three had a very nice looking truck, no signs of any scratches, or dirt, one of those rigs that has four passenger doors and flies on by on 95 hauling shiny snow mobiles or Bayliners. He also wore Carhartts. Crisp Carhartts.

But he also had a clipboard and a gadget so we talked for a bit. Turned out he had once worked for Tree Guy Number One, and also for Tree Guy Number Two.

I explained how the westerly Oak had become my first priority but wondered if there were economies of scale involved—for instance the use of a crane or some other heavy equipment—would it might make sense for me to have them do both trees at once as I had just seen with the neighbor’s seven oaks? He peeled off a swatch of bark from the eastern oak and threw it on the grass. The bare spot on the tree has progressed these last ten years. It’s now above me head and a couple feet wide. The squirrels still come and go.

We looked it all over and he had a look at my line of scraggly white pines too.

Those pines.

You’d have thought they were named Omaha, Utah, Gold, and Juno because it was going to take Eisenhower and the entire allied command to wrestle them down. First a big chunk of the fence at the front of the yard had to come down (we may be able to put it back up). And then probably a few of the hemlocks that make up the front hedge (good riddance, but can you spare the lilacs?).

Perplexing because the driveway seemed like the logical entry point to me, a non-tree guy. Carhartt gently advised me that the problem with my approach was that huge dying oak tree right next to the driveway. The one just to the west side of my house.

The estimate came. My first impulse was to run over to my David’s house to cheer him up about the three thousand he’d spent on his seven oaks. It seemed that each one of my oaks was going to cost more than all seven of his. And oh those pines.

It is possible that Carhartt mistook my willingness to talk about a lot of trees as an indication of something else altogether. As the scope of the job went up somehow the price of each of its constituent parts went up too.

Diseconomies of scale.

All those yard signs must be pricey.

I thought that maybe stick season, just five months away might make me feel better and put the proposal aside. I vowed not to use the hammock.

In July a bluebird caught my attention atop one of the dead limbs high above what remained of his leafy crown. He was spinning a virtuoso bluebird yarn so I stepped inside to grab my binoculars. Sibley says, “During the breeding season males sing, usually from an exposed perch or the tree canopy, to signal territorial possession to prospective mates as well as rival males.” I followed the blue bird around the tree from place top place with my field glasses when I spotted it.

A widow maker.

Eight feet long or so, maybe five inches in diameter, covered with lichen, detached at both ends from the tree itself and just lying there. Perfectly horizontal, dead as could be and above the second floor windows, suspended in the branches it had landed amongst when it separated from the rest of the tree who knows when.

I emailed Tree Guy Number Two. Tree Guy Number Two’s daughter plays lacrosse and I had seen him at a game a few weeks earlier and we chatted, he remembered my easterly oak, but I told him my current concern was a different tree, “Oh that big oak by your driveway?” he recalled.

The eastern oak could be deferred, the western oak could be saved with some heavy trimming and some cabling which would probably cost nearly as much as the removal costs now. And ultimately he would succumb so the judgement was pay now, or pay now and pay again later.

The line of white pines could also wait. Tree Guy Number Two glanced at the pines but focused on his notes about the driveway oak.

“Do you burn wood?” he asked. I would save $375 by keeping all the wood too large to go through the chipper. I do own a wood stove and a chimney intended for it but—but the chimney is probably occupied by bats or chimney swifts now—and, at the moment, the stove and the chimney aren’t mated. I hesitated, and mentioned that a brother in-law burns wood and had expressed interest; I’d make inquiries. A wry look crossed his brow but he said nothing for a couple of beats. No worries, people often hope to make use of the wood but call later to get the larger wood removed. It would cost the same $375 either way.

The plan was for tree guy two to clear some of the weight from the crown in late summer and come back for the trunk and major stems in November. A cancellation saw the whole crew in my driveway in late August. Looking over the paperwork the arborist asked me if I intended to keep the larger wood or if they’d come back to haul it away. When I explained that my brother-in-law would rent a splitter and haul the wood the same wry look crossed the arborist’s face, but his ground crew, hauling implements off the truck just laughed. “If you do need us to come back and get it, it will be easier if he leaves it in long pieces.”