Forty dollars, it turns out. Scores of this set are listed on eBay, ABEBooks.com, and biblio.com. Not only will there be no eureka moment, but lunch money will be hard to find in this lot.

My father, who once owned these 2000 volumes, knew this. He’d wound down his book business as best he could during the last fifteen years of his life. He had not acquired any new titles since the early 1990s. Of course there were books given to him, gifts, and things thrust on him in his professional capacity as a writer and professor of philosophy. And of course he read, so many of those books linger too (a nearly complete collection of the works of Patrick O’Brian, some soft-covered, some hardbacks). And he did get fooled into the Gibbon, but that is another story.

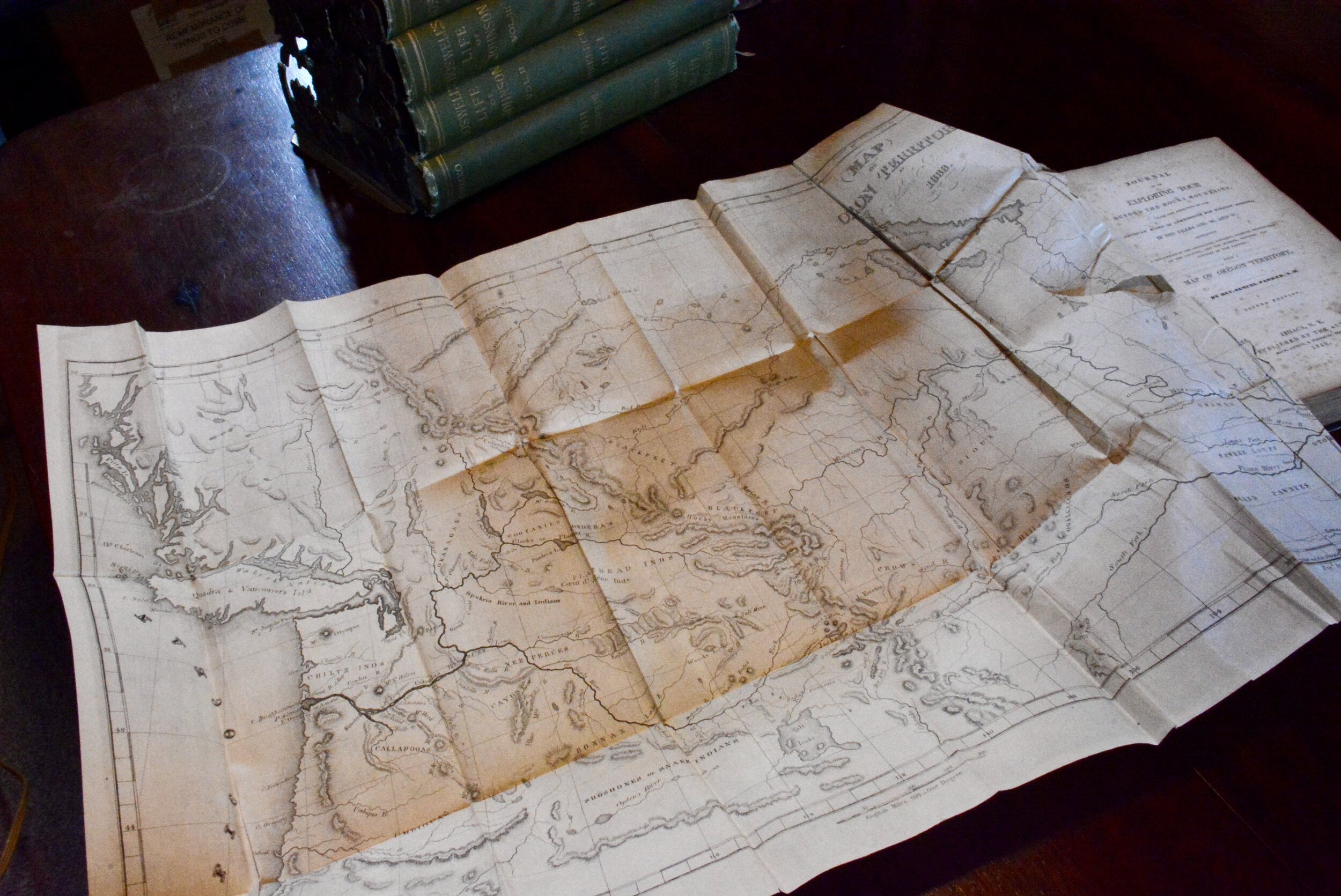

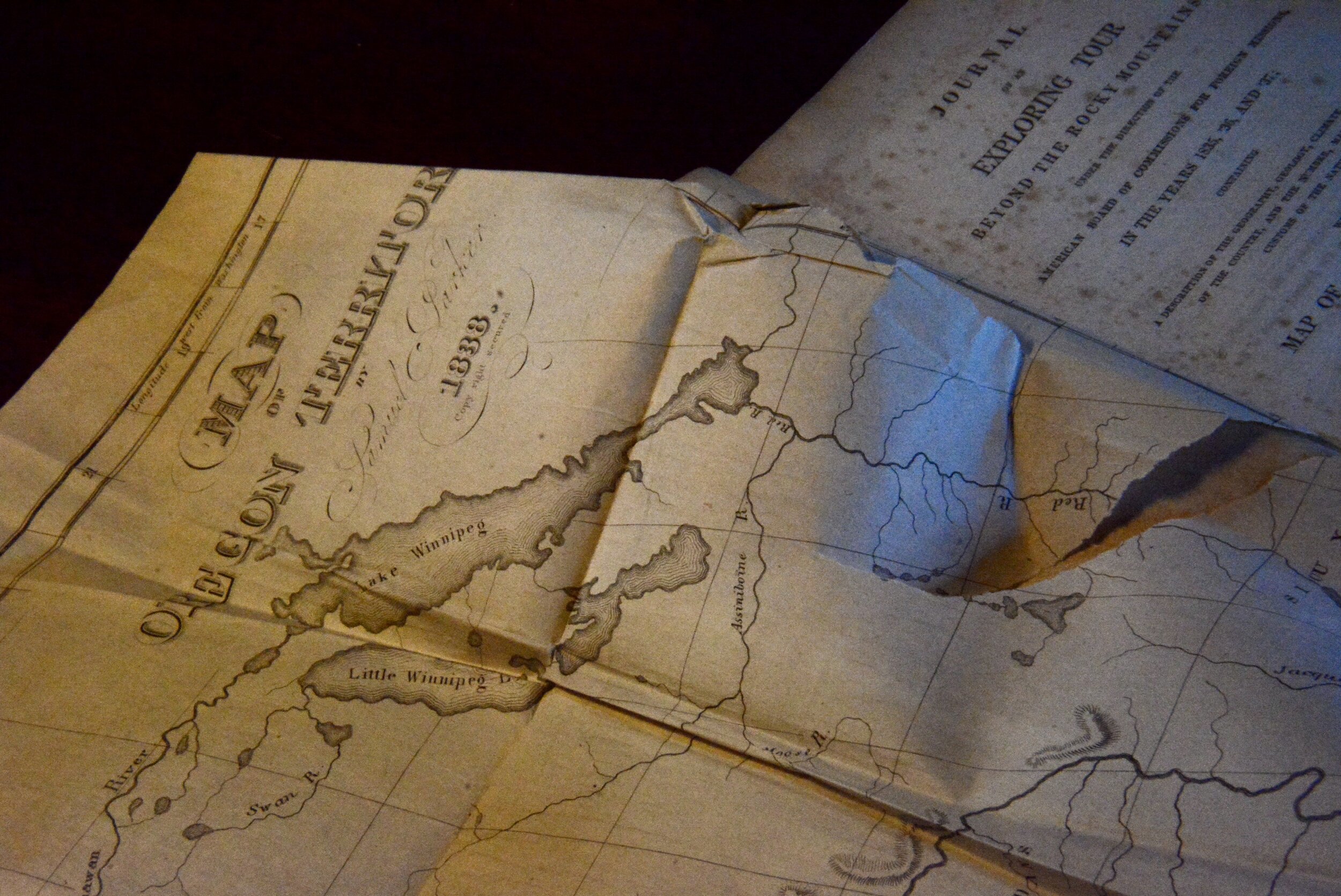

His wartime correspondence with my mother, and his good friend Dick Tansey (Gardner’s Art Through the Ages) always contained tidbits about what book one of them had seen recently, and much perseveration over prices. So book collecting and book hunting were hobbies from his earliest days and loosely connected to his career as an academic. Eventually it blossomed into a business of sorts, Editio Princeps. By the 1960s and through the 1970s he spent good chunks of his spare time wandering the winding and rolling backroads of Northern New England looking for that dusty old jewel.

Every family trip “up the coast” was just an excuse to poke around some nearby “Antiques & Books” place just for “five minutes or so.” These rambles were not completely without interest for my younger sister and me. Captives of our age and lack of independence we, unlike our older siblings, were lured, or dragged along under some pretense.

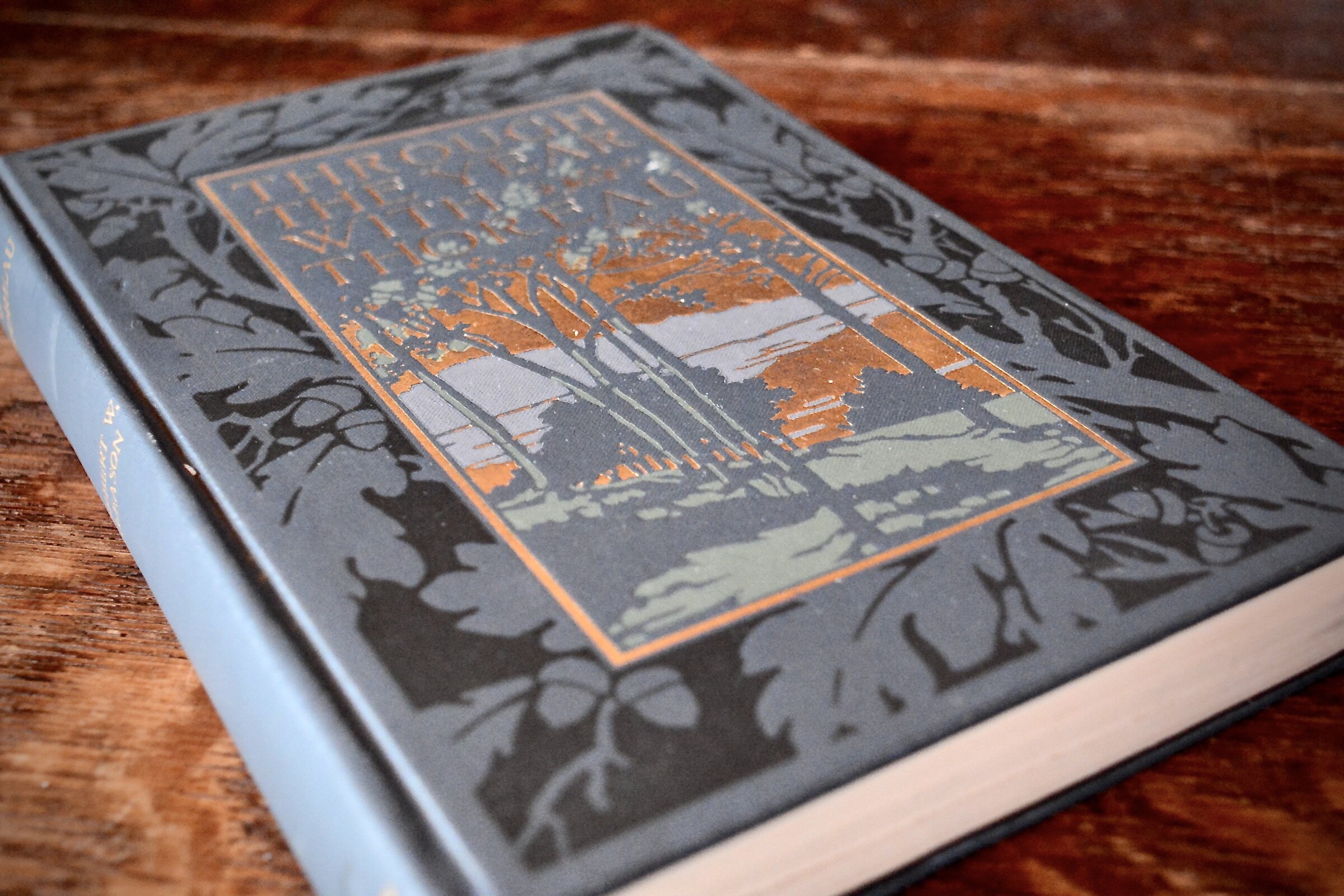

The book barns might be in interesting ocean-side communities or the less traveled parts of Maine. The dank out-buildings held curiosities: ship-models, old fire-arms, uniforms, the colored blown glass balls, riddled with imperfections that once floated fishing gear, or ancient doll houses. Even books—the Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew, Tom Swift—boxes of them, National Geographics so old they had no cover photos. Flea markets had tables lined with old coins, baseball cards, vintage toys, or records. The carnival like atmosphere didn’t suit serious book hunting however. Walden wasn’t going to be found next to an early Elvis statue. The stops in flea markets were likely a sop to my mother who might briefly eye some lamps, old linens, or a decent old soup tureen.

But as it became clear that none of these things were coming back out to Sylvia, the Mercury that my oldest sister hand repainted with a brush in a vain effort to conceal some malfeasance, or the Fiat, itself a mobile curio, we lost interest and drifted back out to fidget under a tree or sit in the back seat disturbing our mother’s reading . My father’s “just five more minutes” grew to consume entire afternoons. Mother had already satisfied herself that the single odd piece of decent silver was owned by a dealer too vulgar to converse with, and that the textiles smelled too moldy to be rescued.

As we traipsed from crossroad to village a couple things always seemed true: the buildings smelled the same, and we were never going to get anything good to eat. Why stop at Round Top Ice Cream when there’s half a package of Stoned Wheat Thins and some ham right in the car?

The dealers were always stashed in an oddly placed barn, or an outbuilding leaning against the side of a declining old New England house. They seemed to coalesce in the smaller towns, bunched near one another like a gasoline alley for old things. The whiff—mouse, foxed papers, the dry sills and space between windows, punky floorboards—was always more or less the same.

The estate sales—auctions generally—might have been in a stately old shingle cottage on a bluff near the water or in a decrepit Italianate place in one of Maine’s smaller mill towns. Sixty years would have passed since the man that built the mill shuffled off leaving his name on the lintel of a nearby school and the once grand family home in the hands of his last matron sister. In turn the old pile ended up owned by a collection of scattered grandnieces and nephews left to claim a few baubles and turn the remnant over to an auctioneer.. With luck this auction would have evaded the attention of the Portland or Massachusetts set—too far inland, no big lake or old summer colony nearby, or maybe it was just November.

Eventually the pretense of a trip up the coast had lost its allure for even my mother. We were left behind and my father was free to adopt a more strategic and business-like approach to his collecting in the 1970s. And Editio Princeps hummed along for fifteen years or so.

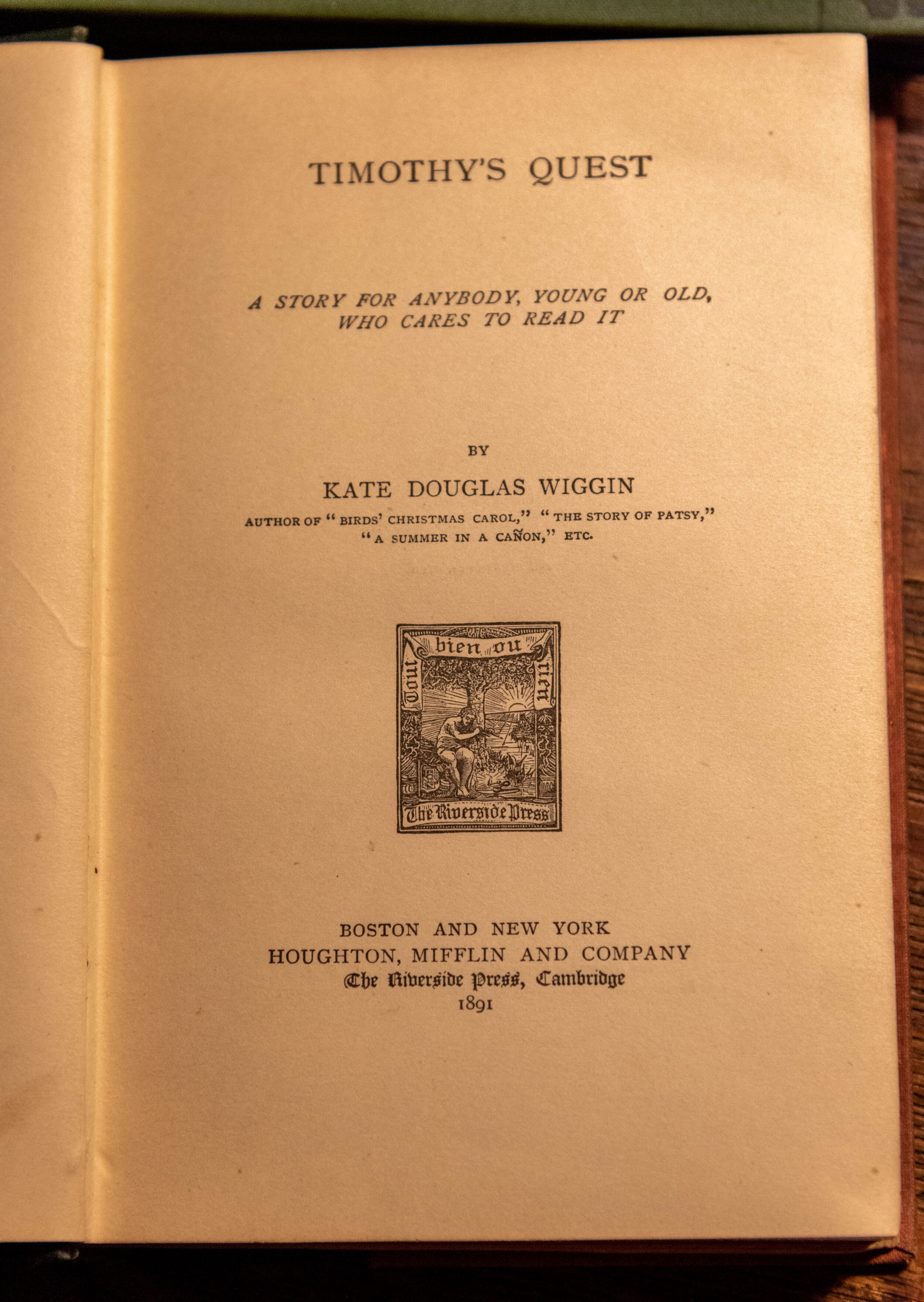

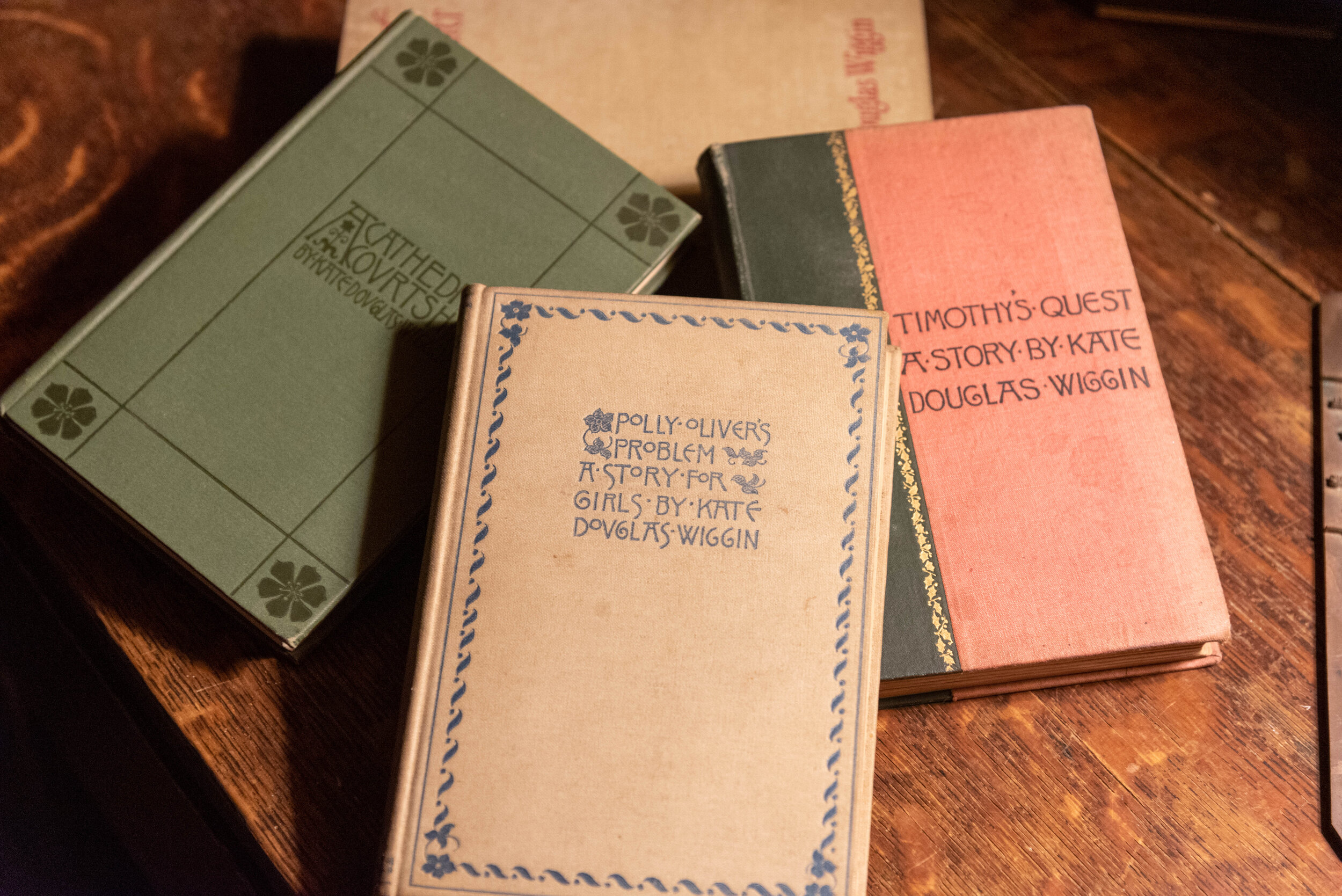

By the 1990s the value of continuing to shop individual titles to buyers and institutions had diminished. My father’s desire to look for new material had pretty much petered out in the 1980s, and shelf space became rare—sure he would still poke into a junk store if he found himself in a new town for a speaking engagement or a college visit, but the days of actively looking for books were over. His “hot” titles had been sold and he was left with a collection of mid-level interest. The effort of marketing far outweighed the payback. In an effort to shed clutter he had begun shipping large lots—“children’s books 1880s”—to auction houses like Swann Galleries (thirty years later, I still get mail from Swann). A periodic check for a few hundred dollars would appear with the mail—his cut, less commissions, fees, and the costs of packing and returning the relict back to Maine.

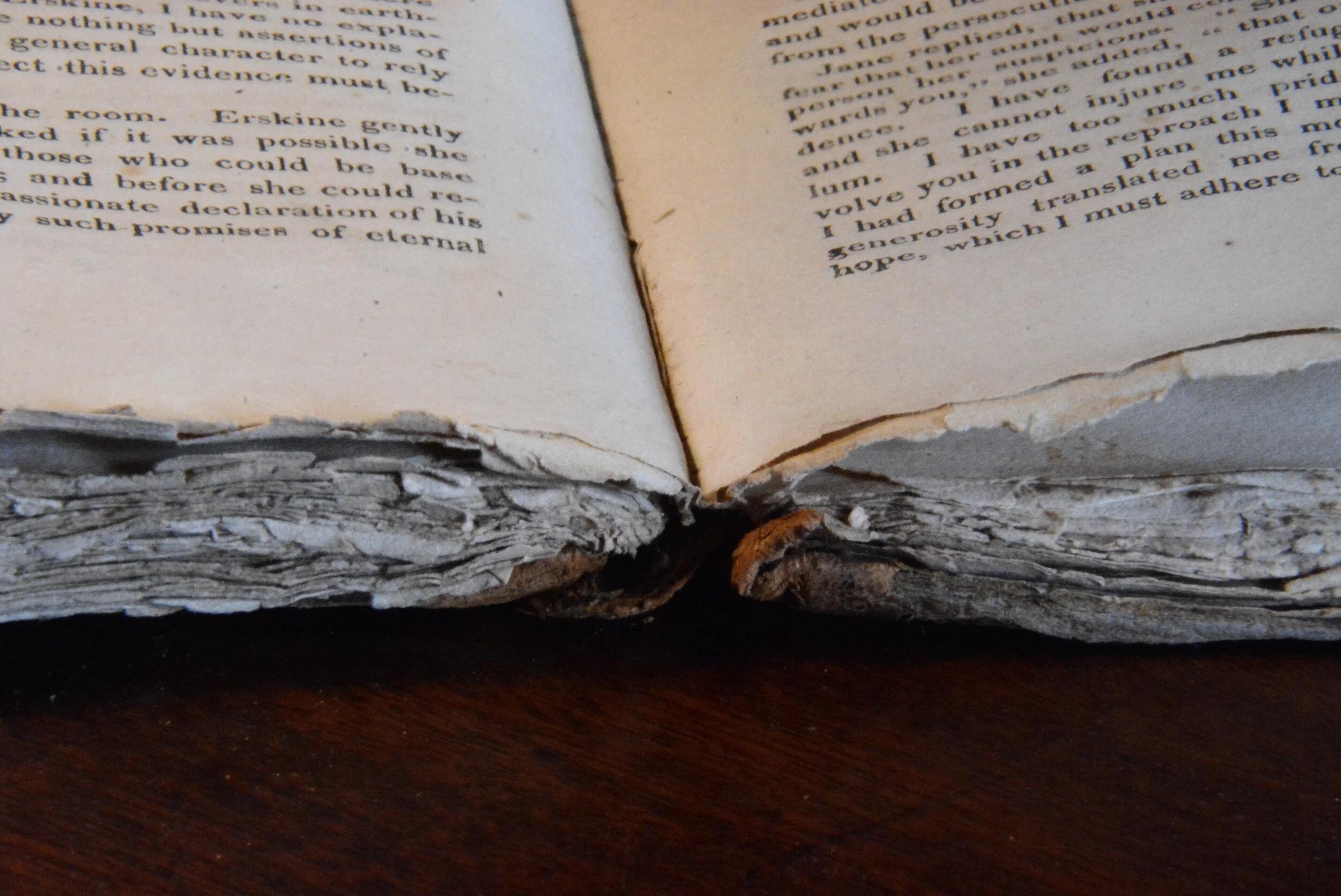

Which relict, always of diminishing interest and value, was returned to the shelves without any effort to re-index or organize, and generally a little worse for its travels. As the millennium ground to a close so too did even these efforts.

Editio Princeps had run its course. The post-office box in the neighboring town was given up, tax write-offs for the Barn Chamber where the books were stored ceased. All that remains is half a box of nicely printed business sized envelopes.

And the books. The Relict.

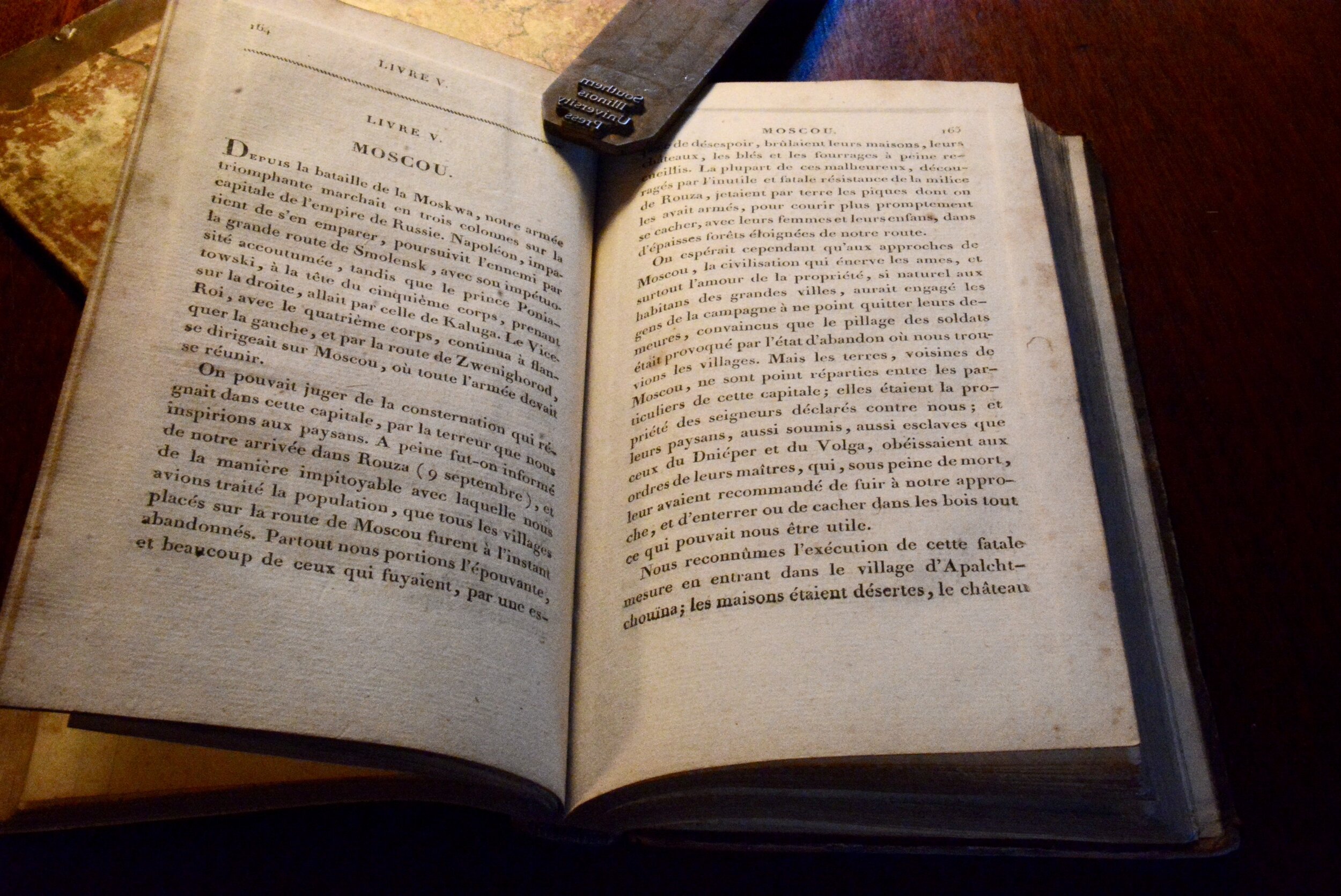

It’s an apt term. The book business has more than a whiff of the church-yard to it: reticence, bordering on secretiveness, ritual, and arcane terminology.

For my father monetizing, as we say now, what started as a hobby borne of his intellectual pursuits was crass at some level. His reluctance to publicly embrace the pursuit verged on embarrassment. Did he feel his friends and colleagues would be on-guard as he eyed their book shelves during faculty get togethers? Was it curiosity or avarice?

On another level he needed to keep his identity as a connoisseur shrouded to succeed. So long as the dealers, flea marketeers, and estate auctioneers took him for a rube he might score. Just as a restaurant critic needs anonymity , my father often bought whole crates of books labelled “lot $10” rather than arouse suspicion by asking for just that one slim Henry James and leaving the rest behind. It made him uneasy: the mild omissions were diminishing. And so the post office box was rented in Topsham away from the curious throng of Brunswick, and a pseudonym underscored all the correspondence.

And what correspondence. Catching a fish is one thing, finding a buyer is another. Finding collections on particular topics at colleges, universities, historical societies, trade associations, and fraternal organizations took leg work.

There was no internet. The internet for book dealers and collectors was a newsletter that appeared on a weekly basis in the old bike basket that served as a mail box on our front porch. The AB Bookman’s Weekly, AB for Antiquarian Bookseller. With a cover page of newsy briefs, it was mainly a source to place and read classified advertisements. I’d eyeball it the same way I might read a cereal box or the “Talk of the Town” in the New Yorker: just idly. I might offer helpful advice, “If you ever found a copy of Alice in Wonderland you’d be rich.”

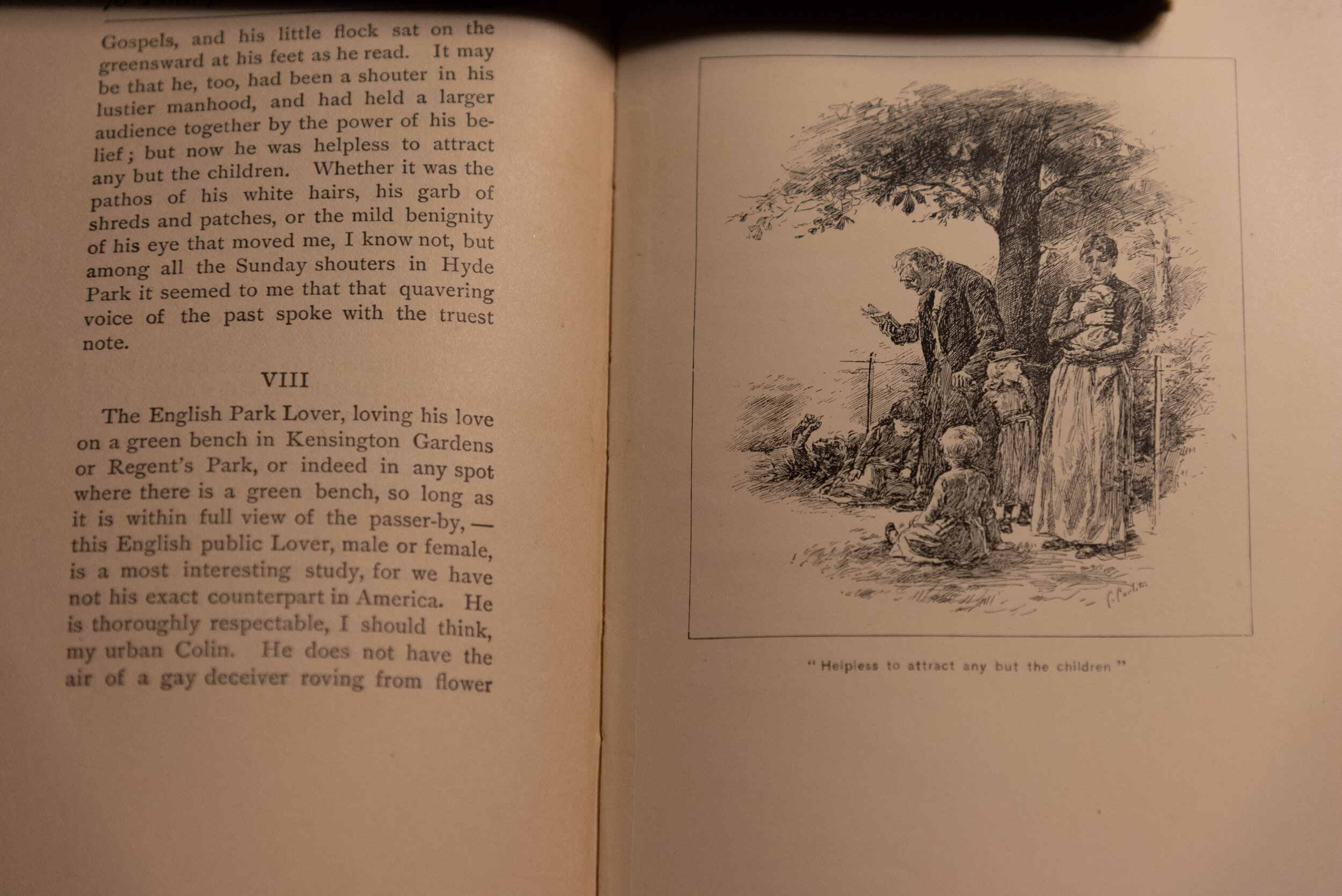

The remoteness and the unfamiliarity of the correspondents led to some stilted language in the offer letters. “Gentleman, we are in possession of, and offer for your consideration, a near fine copy of The Atlantic Monthly, February 1862, Vol IX containing some important work, not frequently found.” As if the offices of Editio Princeps were staffed by a coterie of diligent scholars with an entire department devoted just to civil war literature. As if to name the Battle Hymm of the Republic would curse the deal. As if “we” are not selling something, merely offering it.

The return correspondence was just as strained.

To be sure, Editio Princeps had its victories. A slim volume picked up at a junk store in Livermore, or Jay, for maybe thirty-five cents, sold to a collector far, far away for $715, plenty of other wins in the several hundred dollar range. But plenty of duds too. The unabridged Century dictionary in 14 volumes with companion volumes on proper names and geographic names graces a full shelf and half in my home. It’s old and looks impressive. You can find it listed for two-hundred dollars or so. One-fifty seems like the low end of what current owners hope for so I might aim even lower. But at three feet of shelving and weighing in at eighty-four pounds it is difficult to see the margin. After shipping and the hassle of packaging are considered, the effort and cost of getting it to a buyer make the curb seem like a likely option. But I suppose it can sit there for another three years while I grind through the rest looking for the odd single volumes I can list for forty dollars.

On my half birthday, looking once again at this relict, as I have nearly every day for the past fifteen years, it dawned on me that if I did not do something about it soon it will become my children’s problem. Like the grand nieces and nephews of that mill owner in Norridgewock or Canton, my kids may sell the whole lot, grand shelves included, to a junk dealer.

So down the rabbit hole I have gone. I am giving myself eighteen months to make a credible dent.

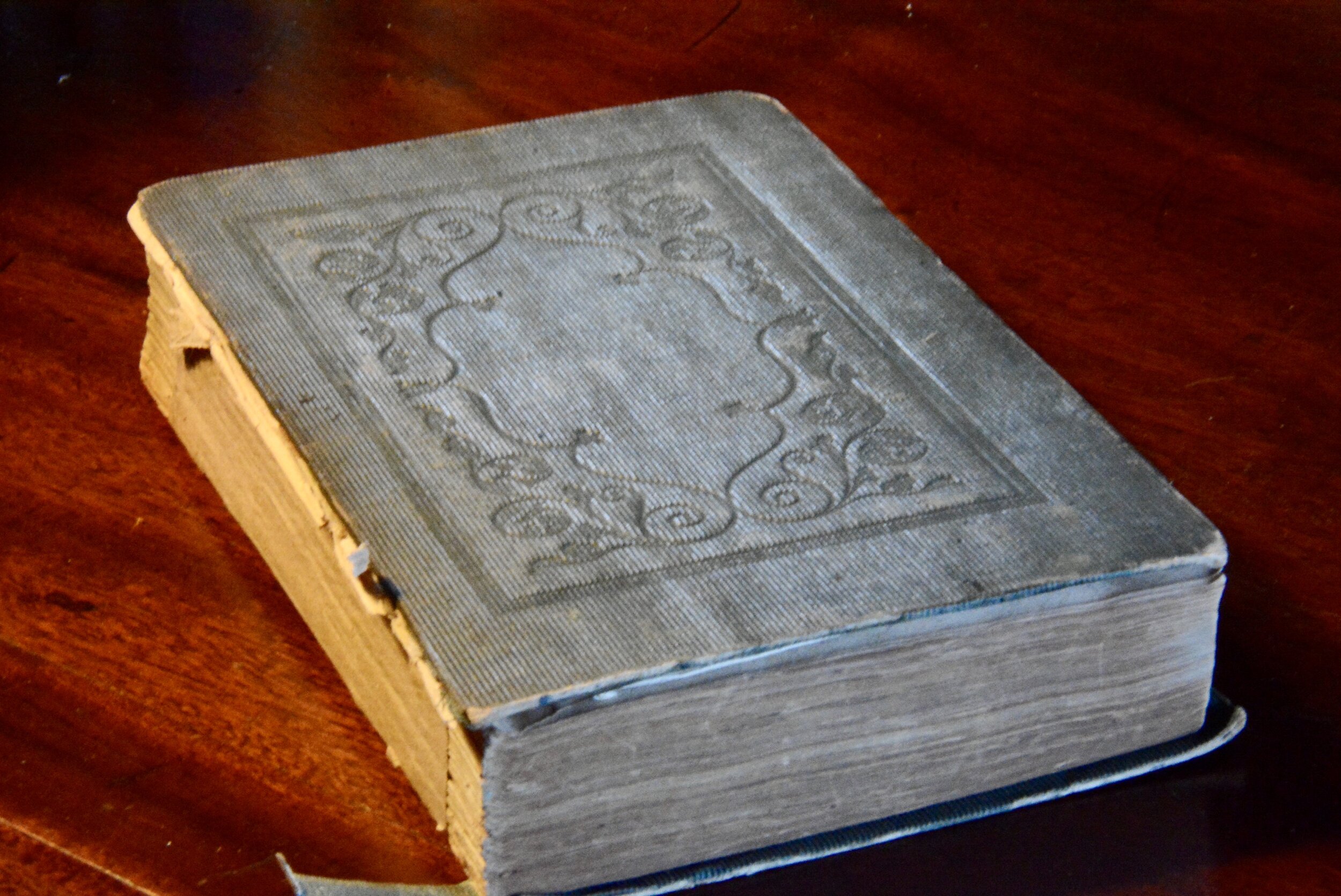

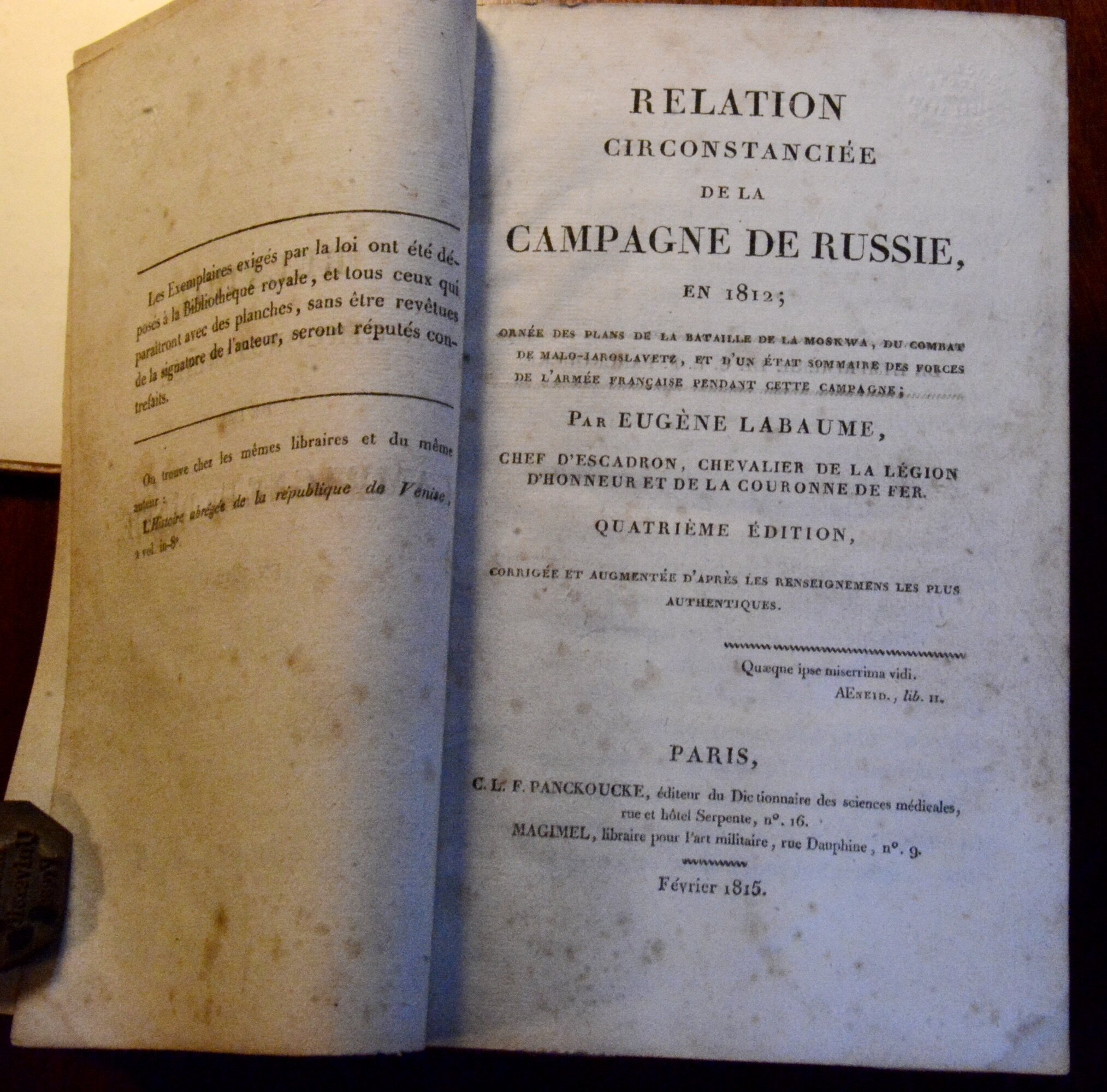

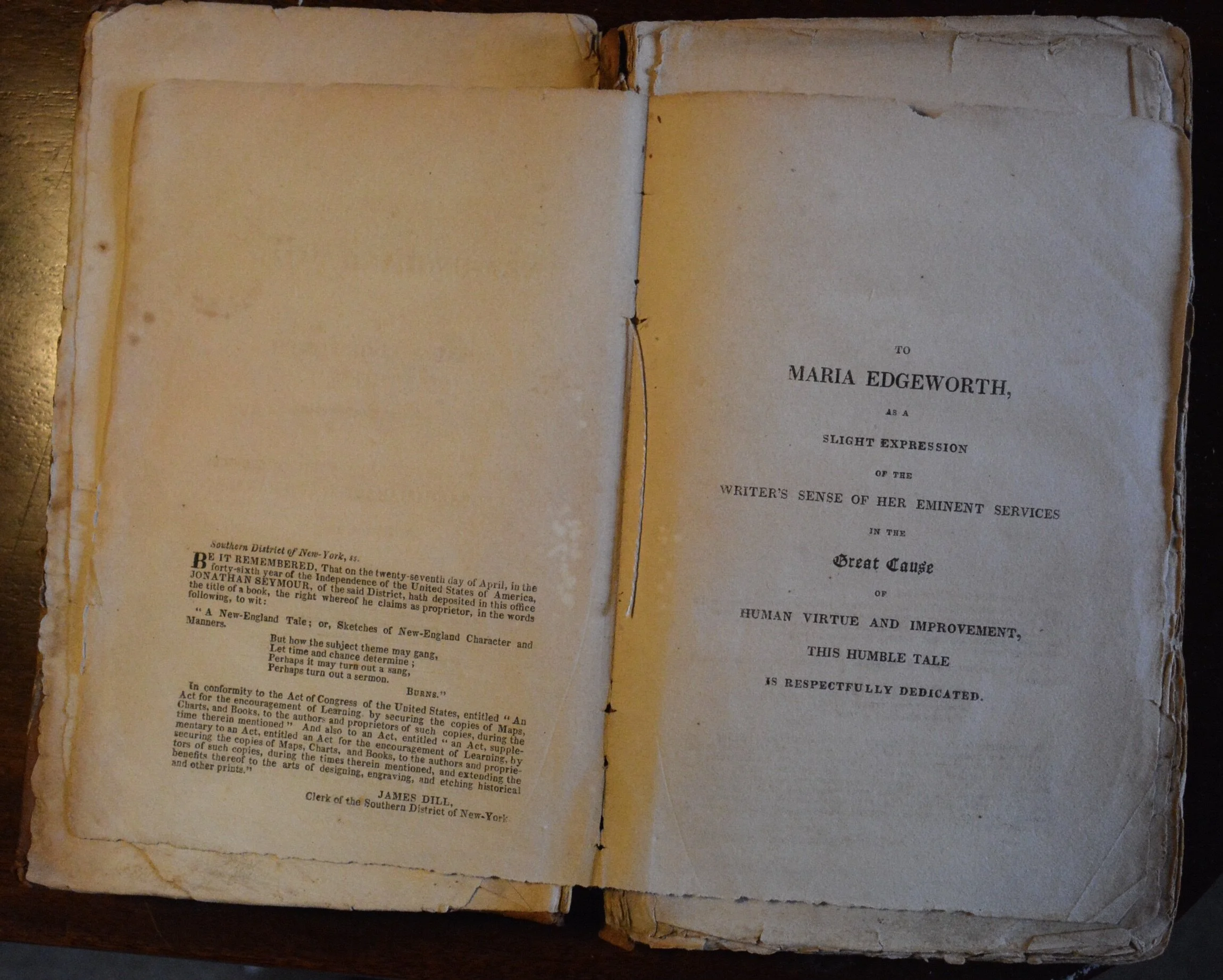

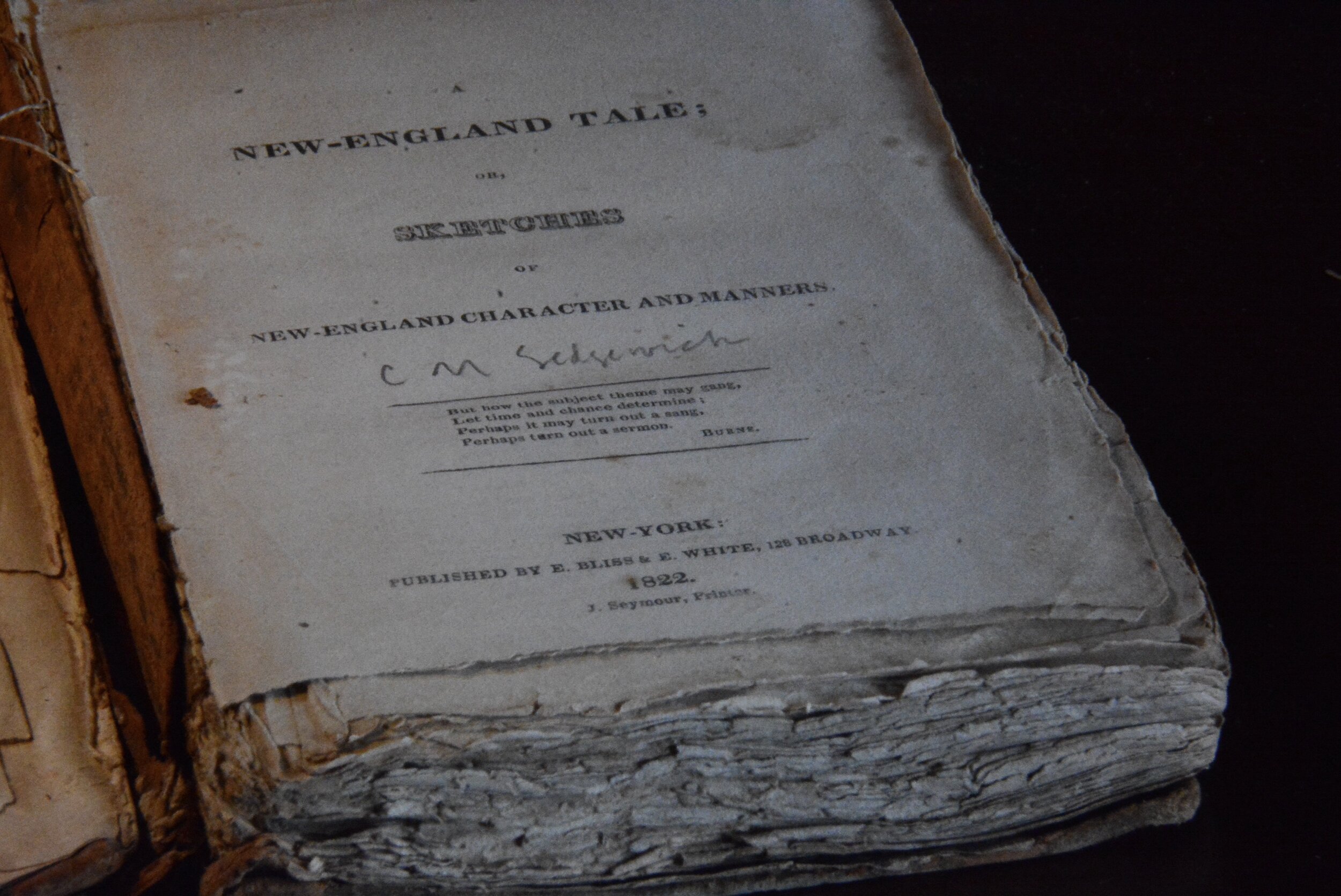

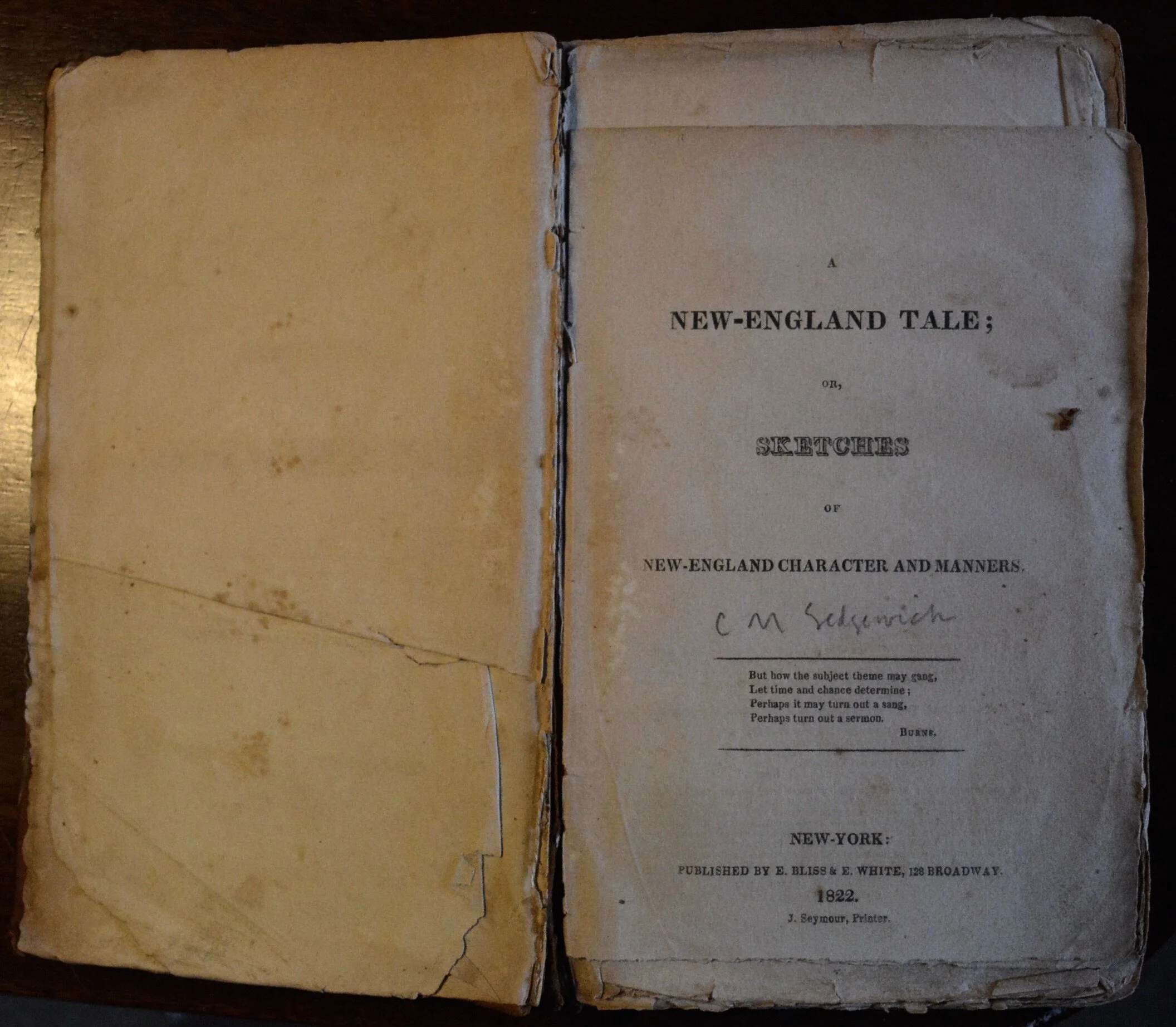

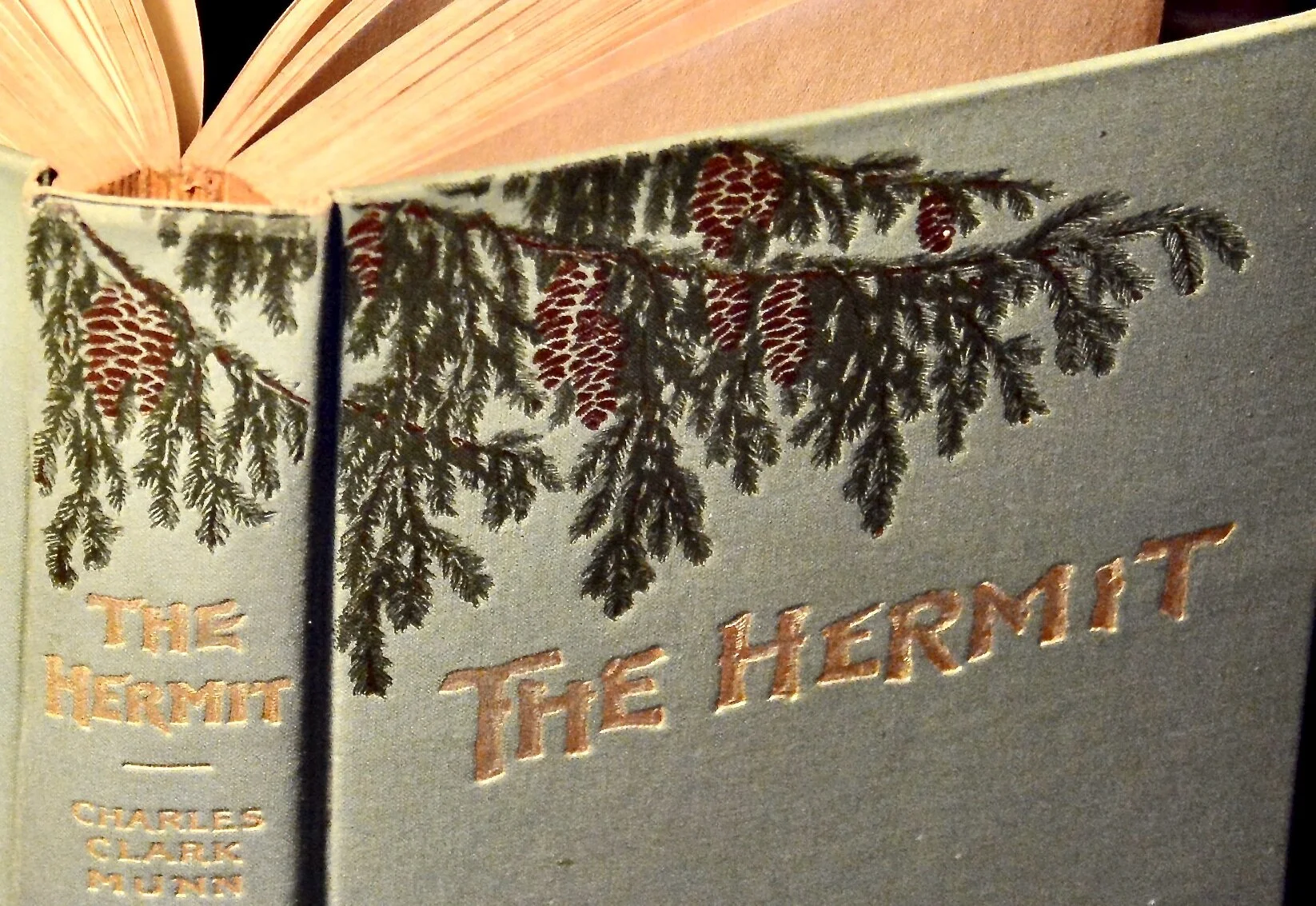

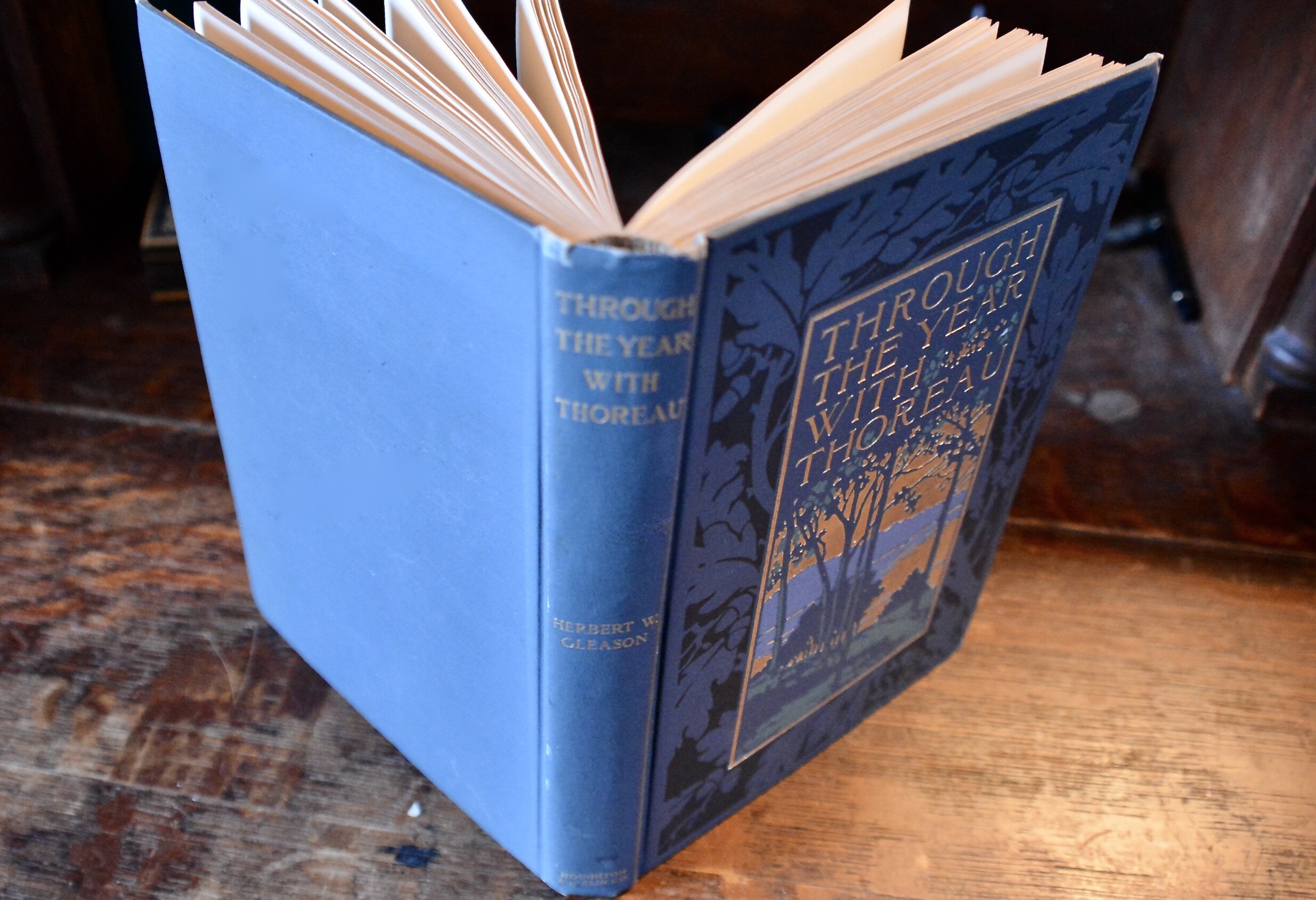

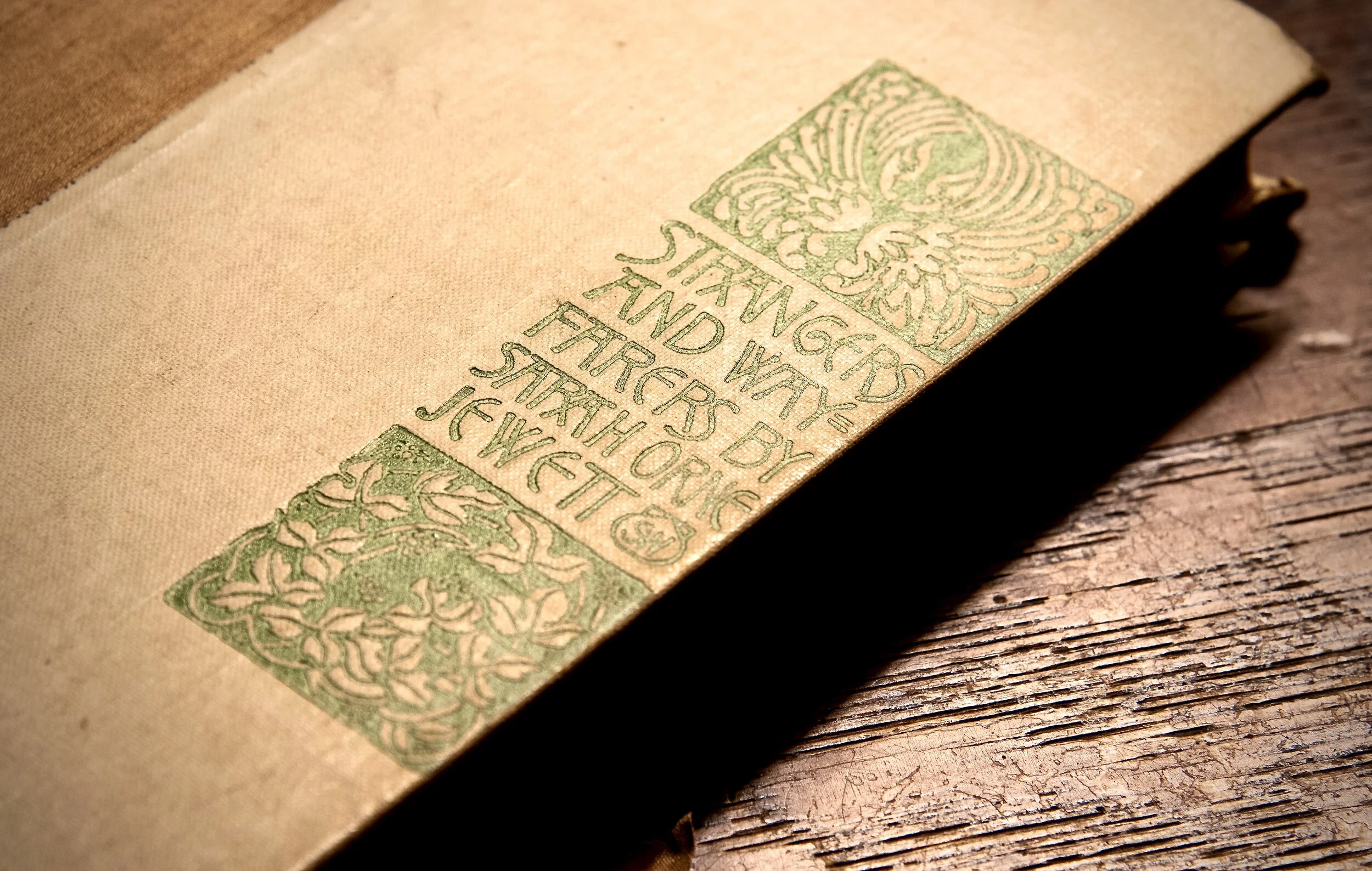

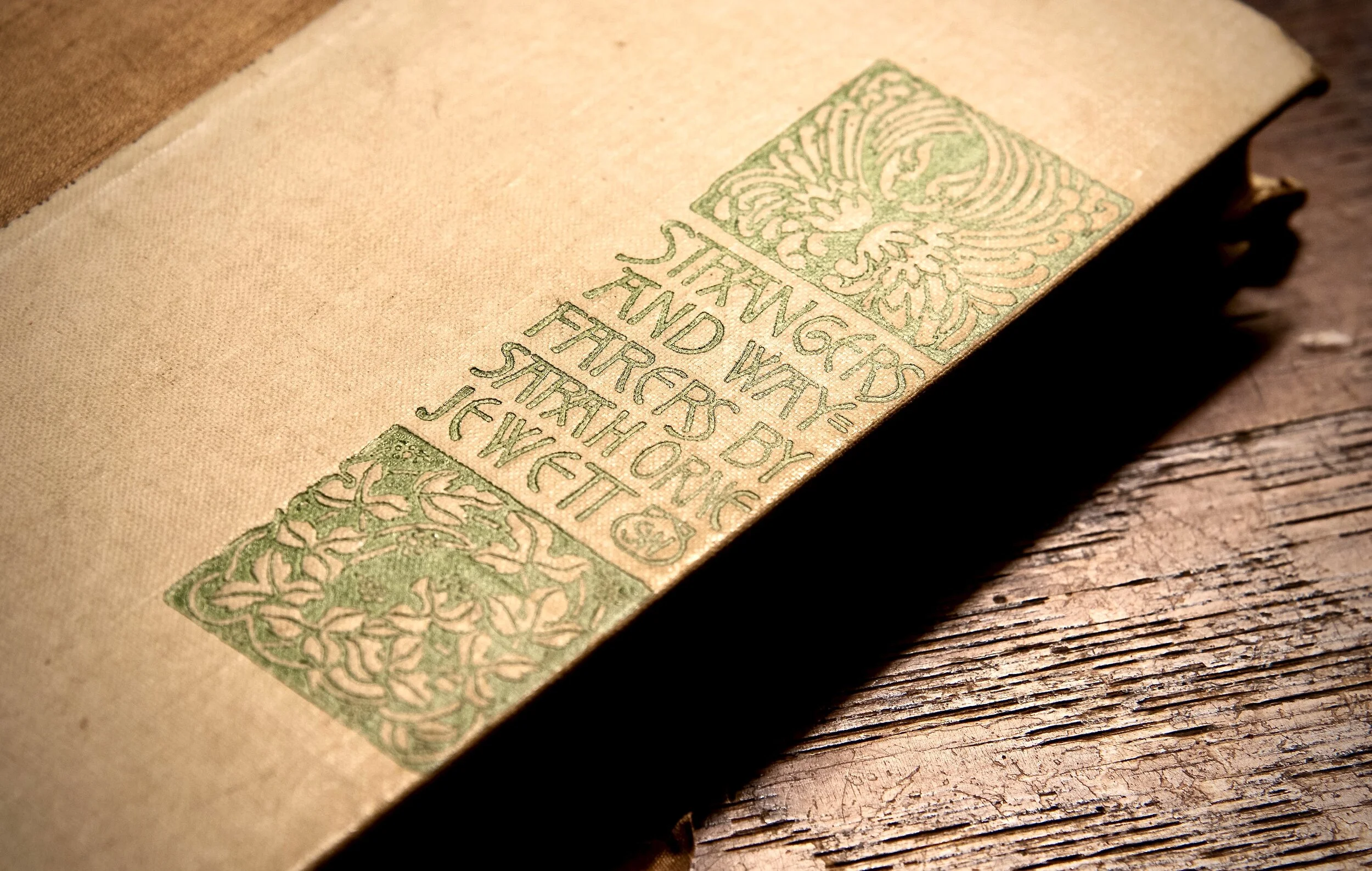

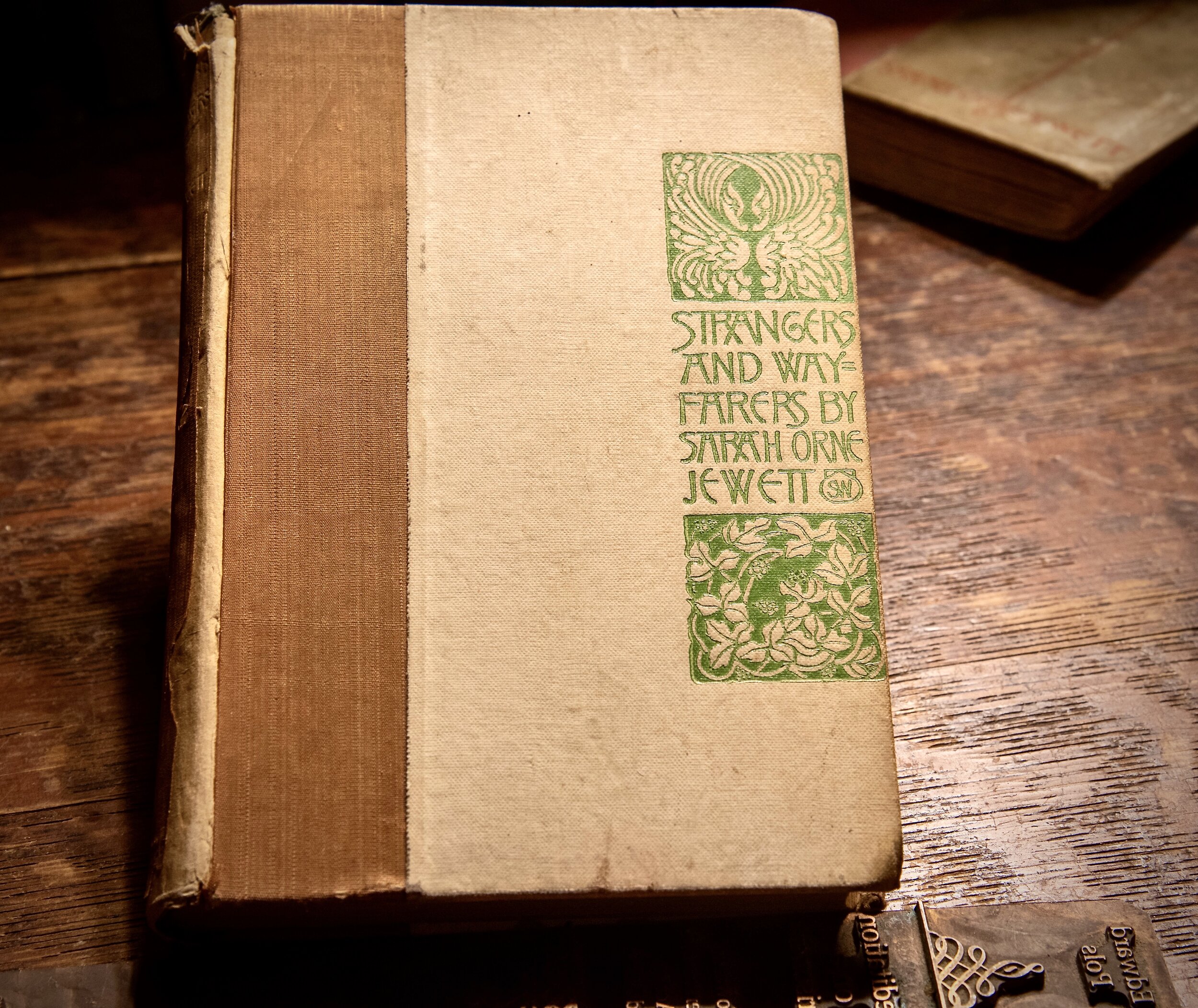

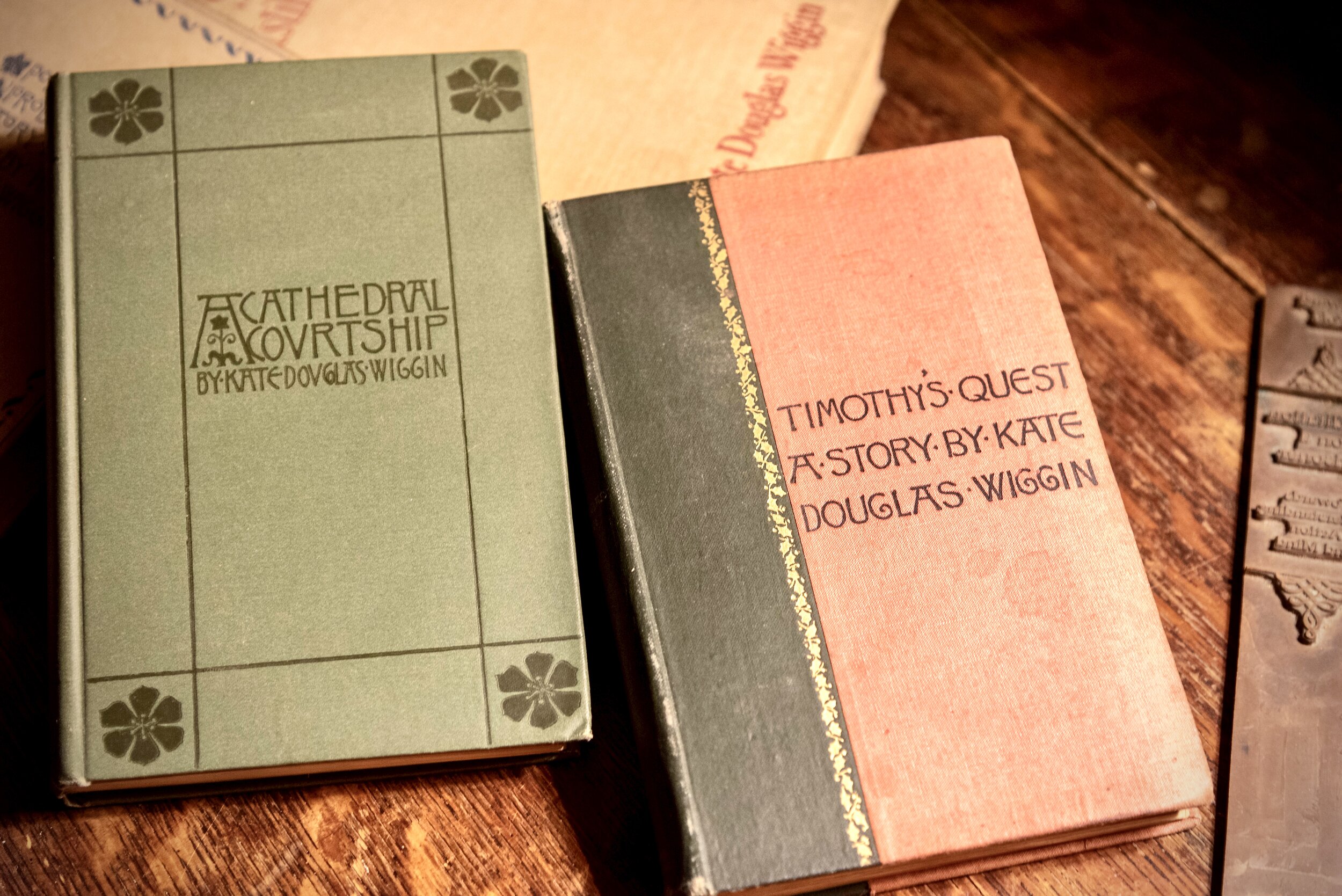

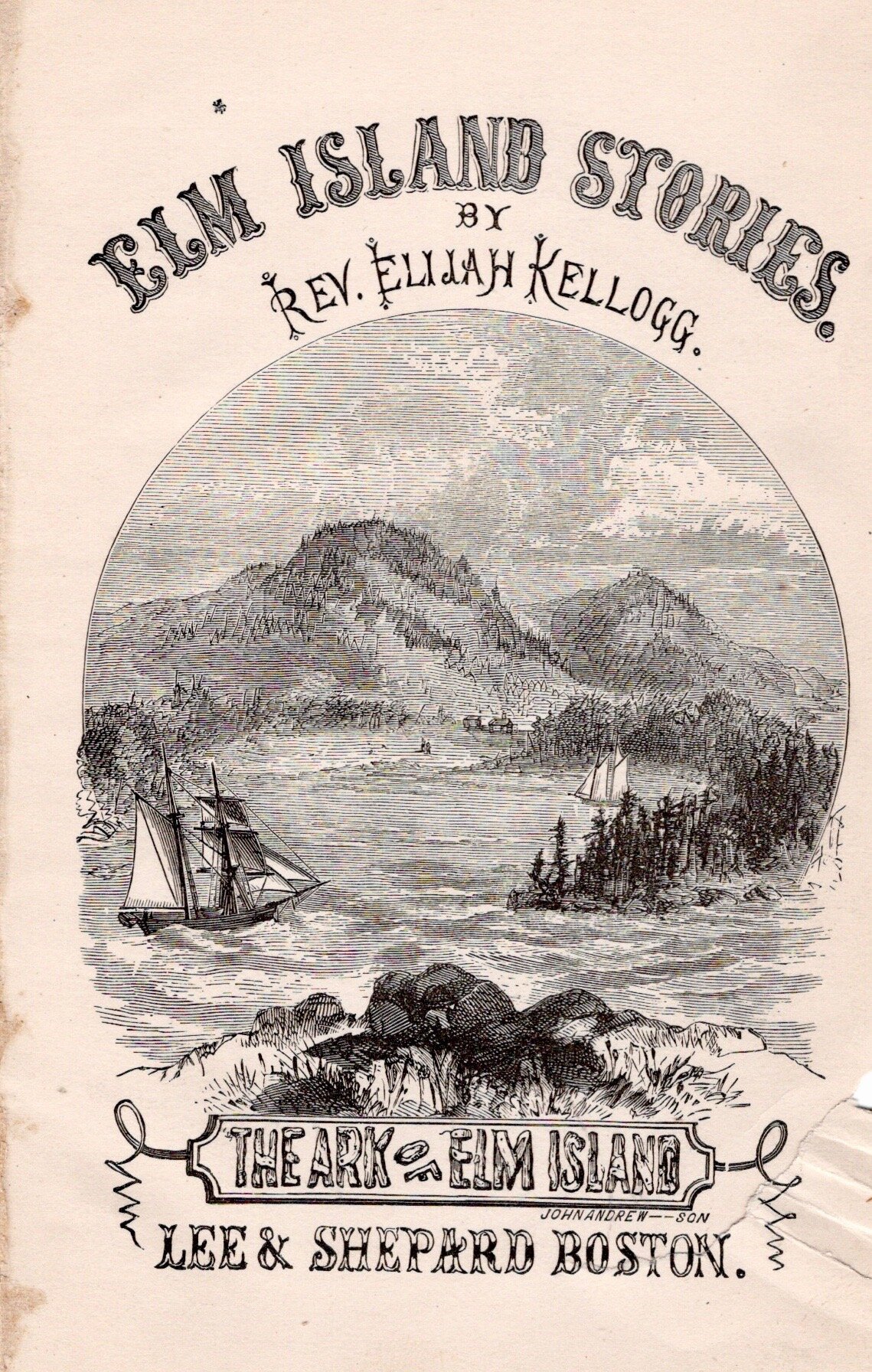

Among the duds, I have found a few nice things. Not diamonds in the rough—more like shiny objects. These shiny objects have value to someone out there—and if I can get them into the hands of someone who values them I will be doing us both a favor.

The difficulty is the contours of the Rabbit Hole itself. I have heard of Rudyard Kipling, he was a very popular writer, there have been entire courses based on this work, therefore first editions of his work must be rare and worth a lot.

Not really. He was so popular everyone had his work; a ton of it, in good shape, fills the internet.

A second facet of the rabbit hole is the desire for something to be valuable just because you like it, or find its mere existence fascinating.

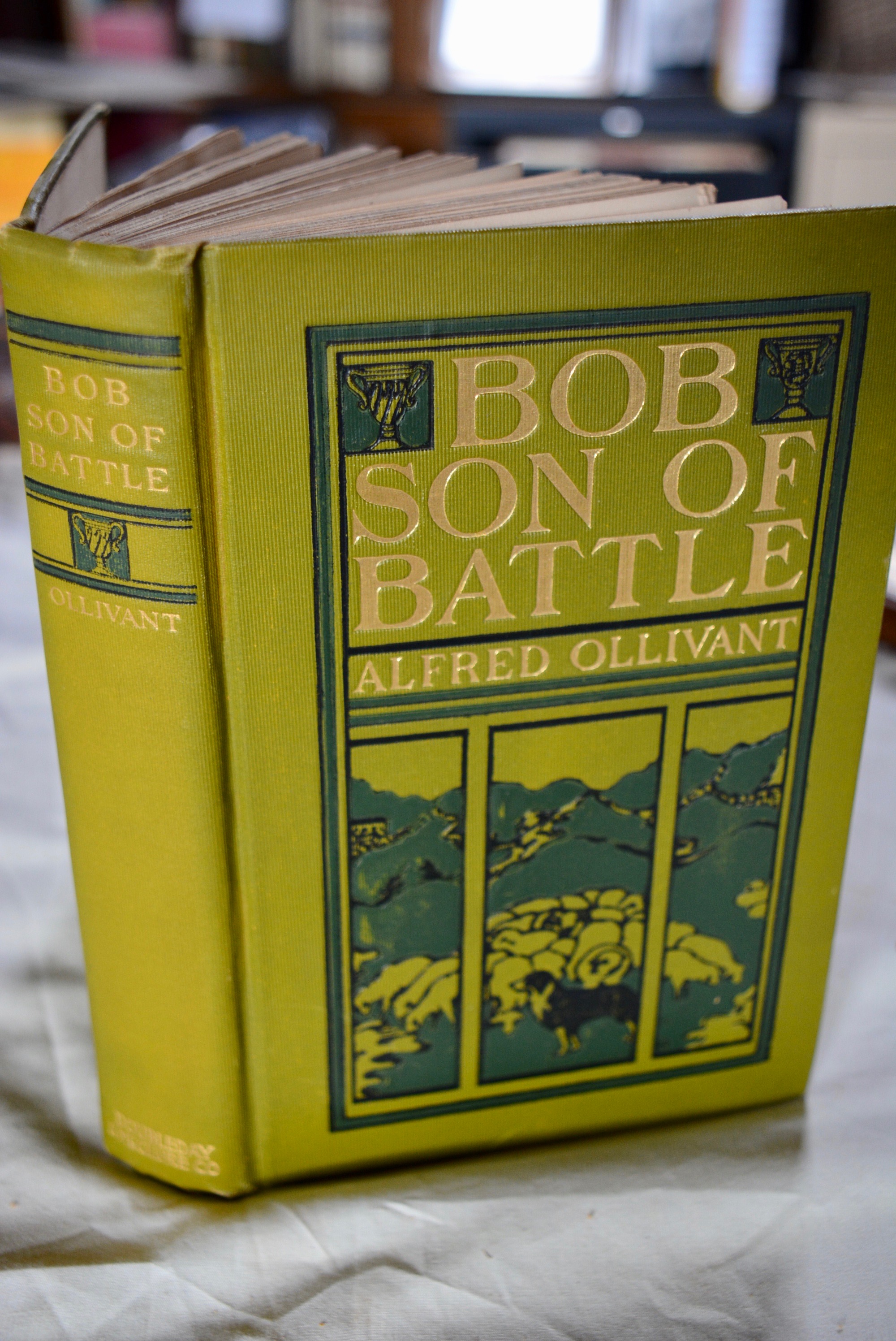

Bob, Son of Battle by Alfred Ollivant caught my attention. Wikipedia summarizes the plot like this:

The story emphasizes the rivalry between two sheepdogs and their masters, and chronicles the maturing of a boy, David, who is caught between them. His mother dies, and he is left to the care of his father, Adam M'Adam, a sarcastic, angry alcoholic with few redeeming qualities. M'Adam is the owner of Red Wull, a huge, violent dog who herds his sheep by brute force. The other dog is Bob, son of Battle. He herds sheep by finesse and persuasion. His master is James Moore, Master of Kenmuir, who acts as surrogate father to David. David and Moore's daughter Maggie become romantically intrigued by each other.

What more could you ask for? Sheepdogs, just like Babe, and romantic intrigue in Scotland, just like Outlander.

It’s an old book, 1901, and in good shape, but it’s just a later printing of the first edition—it can be had for twelve dollars.